Burdock has a clingy nature. It is particularly bad in animal fur.

Arctium minus: Burdock’s Plus Side

I have a confession to make: When I was a kid I had a miniature corn cob pipe. And in it I smoked dried burdock leaf… I think that’s why my voice changed when I was seven.

We conspiratorial kids didn’t call it burdock. It was “snake rhubarb” and it did resemble the rhubarb in the garden… somewhat. My mother found out one day but decided the smoking was punishment enough. It was harsh, hot, dry and a lot of fun until she knew. Only years later would I return to the plant, this time to eat it and grow it.

Burdock is not native to North America. I grow Gobo, which is the original Japanese cultivated version of the plant. I had eaten it many times when I lived in Japan so it was an addition to my garden. Like many temperate plants it doesn’t like the Florida heat. (Horseradish, Lilacs, and Asparagus, for example, completely refuse to grow here.) What most people don’t know is burdock is an escaped plant from Asia. That was rather surprising to me because it was an extremely common weed in southern Maine, which is just about as far from Japan as one can get (I know because I was stationed in Japan while in the military.)

Burdock’s can make two claims to fame: It was in the original recipe for root beer, and, was the inspiration for velcro. Burdock is also the second half of the British drink Dandelion and Burdock. That concoction is even more bitter than Moxie, which is flavored with gentian root. And therein lies the burdock tale of woe: It is on the bitter side. That is how it protects itself from predators, by putting a layer of bitterness on the outside of the plant.

First year roots are the prime fare, young leaves can be eaten but you have to like bitter foods. As the roots age they become more bitter and woody, particularly in their second year. Peeled burdock stems are also edible, and not as bitter as the leaves. One of the reason why I like burdock, especially in temperate climates, is it’s a leaf large enough to wrap wild food in for cooking in the campfire. Wrap up a trout with some wild garlic and Northern Bay leaves and roast in the embers: Life is good. (See recipes on bottom of page.)

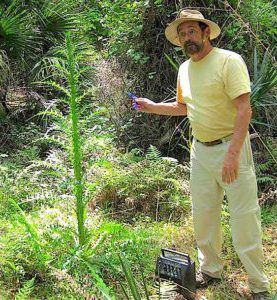

Burdock is in the same family with daisies, chicory, thistles and dandelions. There are at least three species of burdock in North America, all edible and all imports. The most common is the “lesser” Arctium minus. (ARK-ti-um MYE-nus) It grows from knee to shoulder height and is found just about everywhere except Florida. The “great burdock” and the “wooly burdock” are less known. The “great” can grow to nine feet high but usually doesn’t but its flowers are larger than the minus. The “woolly” has “fleece” on its flower heads.

The species name Arctium is Latinized Greek. The Greek is “arktos” meaning bear, in reference to the round, brown burs. Minus means the lesser or smaller since the Great Burdock (A. lappa) is larger. A. Lappa (LAH-pah) is a combination of Latin and Greek and means bur and to seize. A. tomentosum (toe-men-TOE-sum ) is the wooly burdock. Tormetosum means fuzzy or hairy.

Green Deane’s “Itemized” Plant Profile

IDENTIFICATION: Biannual. First year plant a low circle of rhubarb looking leaves with a foul odor. Second year flowering stalk, bushy, many purple flowers, thistle-like burs. Leaves usually large, ovate, woolly underneath, leafstalks usually hollow.

TIME OF YEAR: Middle summer to late fall, even after a frost, just mark where they are.

ENVIRONMENT: Sun or part shade, any type of well-drained soil. Grows a huge tap root so loosened soil is helpful to harvesting. Normally found along roadsides, barnyards, fence lines, disturbed soil, under bird feeders.

METHOD OF PREPARATION: First year roots can be eaten raw, or can be slow roasted for many hours making them sweeter. Older first year roots — scrubbed –boiled 20 minutes. Young shoots boiled until tender, more if bitter. Second year, stems peeled before flowering and boiled 20 minutes. Seed sprouts edible. Young leaves boiled edible but bitter. Leaf stems peeled and boiled. Also leaves can be wilted by fire then used for wrapping food.

HERB BLURB

Burdock has anti-bacterial and anti-fungal proprieties. It’s anti-cancer properties similar to broccoli and cabbage. Burdock is also a diuretic and the roots can be laxative.

Dandelion and burdock beer ingredients:

1 lb Young nettles

4 oz. Dandelion leaves

4 oz. Burdock root, fresh, sliced

-OR-

2 oz. Dried burdock root, sliced

1/2 oz. Ginger root, bruised

2 each Lemons

1 g water

1 lb +4 t. soft brown sugar

1 oz. Cream of tartar

Brewing yeast ( see the manufacturer’s instructions for amount)

Dandelion and burdock beer preparation:

1. Put the nettles, dandelion leaves, burdock, ginger and thinly pared rinds of the lemons into a large pan. Add the water.

2. Bring to a boil and simmer for 30 mins.

3. Put the lemon juice from the lemons,1 lb. sugar and cream of tartar into a large container and pour in the liquid thru a strainer, pressing down well on the nettles and other ingredients.

4. Stir to dissolve the sugar.

5. Cool to room temperature.

6. Sprinkle in the yeast.

7. Cover the beer and leave it to ferment in a warm place for 3 days.

8. Pour off the beer and bottle it, adding t. sugar per pint.

- 9.Leave the bottles undisturbed until the beer is clear-about 1 week.

Nettle, Dandelion and Burdock Beer

Ingredients: 450g young nettles

120g dandelion leaves

120g fresh, sliced or 60g dried burdock root

15g root ginger, bruised

2 lemons

4.5 litres water

450g plus 4tsp. demerara sugar

30g cream of tartar

Brewer’s yeast (see manufacturer’s instructions for amount to use)

Put the herbs and the thinly pared rinds of the lemons into a large pan with the water. Bring to the boil and simmer for 30 minutes. Put the lemon juice, 450g of sugar and the cream of tartar into a large container and add the strained liquid from the pan, squeezing the herbs well. Stir to dissolve the sugar and cool to blood heat. Sprinkle in the yeast. Cover the beer and leave to ferment in a warm place for three days. Rack off the beer and bottle it, adding half a teaspoon of sugar per pint. Leave the bottles until the beer is clear – about one week.

This recipe will make a strong syrup which will then need to be watered down with soda 1:4.

Heat 1.5 litres of water in a pan, when boiling add:

* 2 teaspoons fine ground dandelion root (Might need a mortar & pestle)

* 1.5 teaspoons fine ground burdock root (Might need a mortar & pestle)

* 5x 50p sized slices of root ginger

* 1 1/2 star anise

* 1 teaspoon of citric acid

* Zest of an orange

Leave that little lot to simmer for 15-20 minutes, it will smell a lot like a health food shop, then strain through a tea towel, muslin isn’t really fine enough. Whilst the liquid is still hot you need to dissolve about 750g sugar. If you prefer is sweeter or ‘not-sweeter’ adjust the sugar. If you’re finding the drink a bit flavourless simply add more sugar, it accentuates the flavours of the roots and anise. In the summer mix it with plenty of ice and stir through borage flowers for the ultimate English soft drink! Enjoy.

Greek Cardune , with thanks to Wildman Steve Brill

4 cups immature burdock flower stalks, sliced, parboiled 1 minute in

salted water (to remove the bitterness), with dashes of any vinegar

and olive oil

2 cups water or vegetable stock

2 red onions, sliced

1/4 cup olive oil

4 small tomatoes, sliced

2 cups carrots, sliced

2/3 cups basmati brown rice

3 tbs. fresh dill weed, chopped

The juice of 1 lemon

2 tsp. salt, or to taste

1/4 tsp. white pepper, ground

Simmer all ingredients together over low heat in a covered saucepan 70

minutes, or until the rice is tender.

Serves 6 to 8

Surinam Cherries, which are not really cherries, can have a wide fruiting period. So far this season I have found shrubs with tiny green fruit to a large tree-shaped specimen already dropping ripe fruit. I think the latter has jumped the season significantly. There are two varieties, black fruited and deep red fruited. Surinam Cherries taste awful until totally ripe. Even then many folks do not like the flavor. Your pallet will either say this is food or this is not. No in betweens. Seriously. You either will eat them again or never again. But if you are going to eat them make sure they are very ripe. In the black/dark purple variety they are indeed black when totally ripe. With the red-fruiting variety you want a deep fire-truck red (with blue tones) not an orange Ferrari red.

Surinam Cherries, which are not really cherries, can have a wide fruiting period. So far this season I have found shrubs with tiny green fruit to a large tree-shaped specimen already dropping ripe fruit. I think the latter has jumped the season significantly. There are two varieties, black fruited and deep red fruited. Surinam Cherries taste awful until totally ripe. Even then many folks do not like the flavor. Your pallet will either say this is food or this is not. No in betweens. Seriously. You either will eat them again or never again. But if you are going to eat them make sure they are very ripe. In the black/dark purple variety they are indeed black when totally ripe. With the red-fruiting variety you want a deep fire-truck red (with blue tones) not an orange Ferrari red.

Donations to upgrade EatTheWeeds.com and fund a book are going well and has made the half way mark. Thank you to all who have contributed to either via the Go Fund Me

Donations to upgrade EatTheWeeds.com and fund a book are going well and has made the half way mark. Thank you to all who have contributed to either via the Go Fund Me