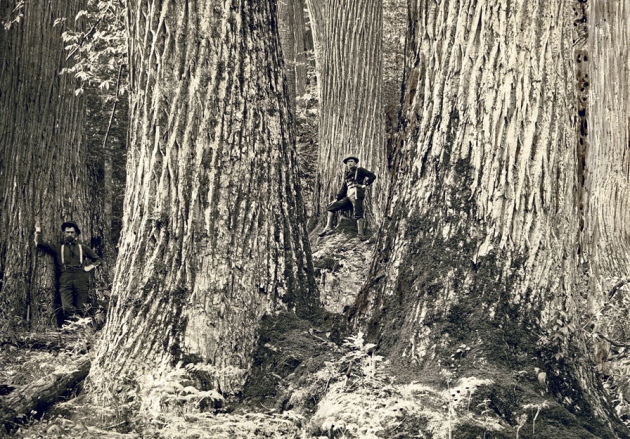

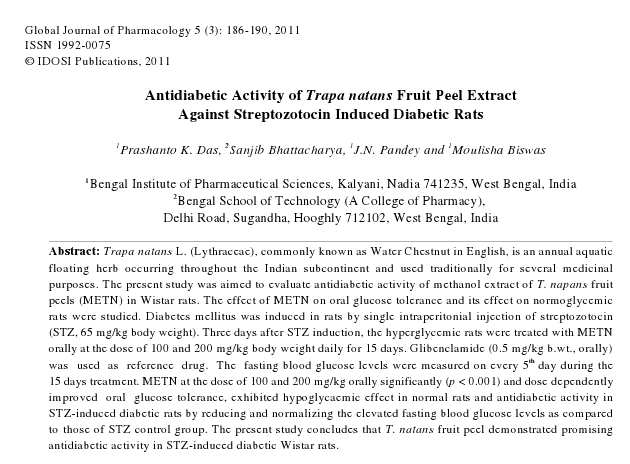

American chestnuts in the Great Smokey Mountains of North Carolina in 1910.

Chestnuts have done more than just disappear from the landscape: They have dropped out of our lives save for a token appearance at Christmas.

Chestnuts, note flat and round side.

Whether in Eurasia or North America chestnuts were a major staple. Long before the cultivation of wheat entire European populations lived off chestnuts as later populations would depend on potatoes. In North America in the Appalachians Mountains one out of every four trees was a Chestnut (Castanea dentata) which the native relied upon heavily. Chestnuts grew to towering heights often supported by a trunk that had no branches until to 50 to 70 feet up. They had boles six feet through and 22 feet around. Prior to 1900 it was the wood most houses, barns and caskets were made of. All of the original telegraph poles were chestnut as were railroad ties. So what happened?

Chestnut leaf has large teeth

In Europe the chestnut (Castanea sativa) became viewed as poor people’s food. Why? Because chestnut flour has no gluten and won’t rise when you make bread with it whereas wheat flour takes readily to yeast. Thus the poor had to eat what they called “downbread.” A staple that sustained marching Greeks in 400 BC to nearly all Italian farmers in the 1800s simply became in time ignored. Then in North America a chestnut blight was noticed in 1904 in the Bronx zoo, New York City. Forester Hermann Merkel, who discovered the infection, took a sample to the New York Botanical Garden across the street. There mycologist William Murrill identified the disease, Cryphonectria parasitica, aka Endothia parasitica. Within a few decades it wiped out some four billion trees leaving by 1950 only a few isolated pockets mostly in northwest United States. Like the invasive species the Water Hyacinth, the blight was probably introduced in 1876 when a lot of Japanese plants (and Asian pathogens) were imported to America for centennial celebrations.

Also note point on the bottom of the nut.

With the blight the chestnut moved into the reference notes of history. However there has been a breeding program with remains of North American chestnuts with the Chinese Chestnut to create a 94% American Chestnut that is immune to the disease. It has worked successfully so far in Virginia and a few other areas. In another generation we might begin to know how successful that program is. The restoration website is the American Chestnut Foundation. When you consider it will take certainly a century or much more to bring back the chestnut this is a group of dedicated, unselfish folks with a long-term view. One plan is to plant resistant chestnuts on land made barren by strip mining.

Europe now provides most of the “sweet” chestnuts.

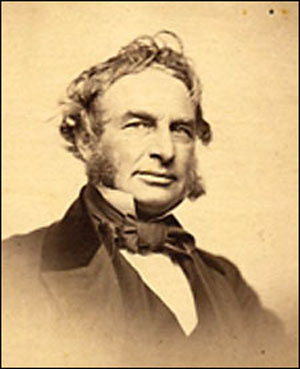

While our edible chestnuts sold at Christmas time come from Europe — which did not suffer the blight — Native Americans made much use of the native chestnut. The first record of them made in North America by a European comes from 1539 by Spaniard Rodrigo Ranjel, secretary on the DeSoto Excursion. He noted Chestnuts trees were similar to the ones back home and mentioned seeing them used in a village near Florida’s Santa Fe river. Thomas Harriot in 1590 said of the Algonquians in North Carolina: Chestnvts there are in diuers places great store: some they vse to eate rawe, some they stamp and boil to make spoonmeate, and with some being sodden they make such a manner of downbread as they vse their beanes.”

Polymath and plant guy Thomas Harriot

The now-famous Captain John Smith of Pocahontas fame wrote in 1612 the Virginia Powhatans boiled chestnuts for four hours making a “both broath and bread for their chiefe men or at least their greatest feasts.” B. Romans wrote in 1775 the Creeks had for food “dry peaches and persimmons, chestnuts and fruit of the chamaerops” (palm fruit.) Merritt Fernald of Harvard (b.1873) probably referring to the Cherokee, said “the nuts were cooked in their corn-bread, or, when roasted, were used like coffee.” We also know the Cherokee boiled the nuts, pounded them with corn (or berries) and wrapped the mixture in a green corn husk to be boiled. Several native nations made bread out of the chestnuts. While the chestnuts don’t have much oil (2%) it was used as a gravy.

Carolina Parakeet

Man was not alone in his use of the chestnut. Woodland creatures like them such as squirrels, mice, bear, deer, turkeys and rabbits. In Australia and Tasmania where European chestnuts thrive kangaroos, wallabies and possums can be a problem. The American chestnut was also food for two now extinct birds, the Carolina Parakeet and the Passenger Pigeon. Incidentally, the Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis) was probably only one of three birds toxic to eat and the only one in North America. Like the other two toxic birds, the Hooded Pitohui and the Ifrita kowaldi, both of Papua, New Guinea, it is because of diet. The two New Guinea birds eat toxic insects which makes them toxic. The Carolina Parakeet was known to eat the toxic seeds of the Cocklebur. John Audubon himself reported cats died from eating the parakeet.

Scored and cooked chestnuts still in their shells

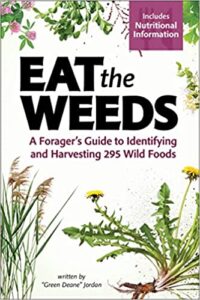

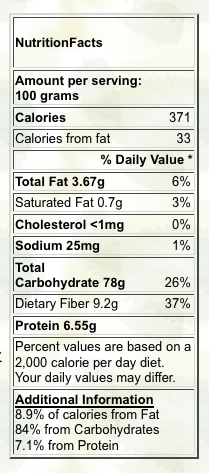

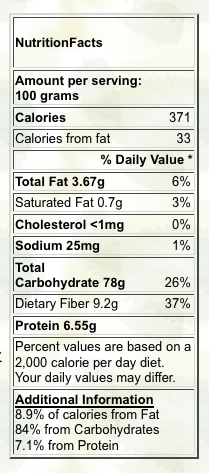

Chestnuts are the only cultivated and consumed nut that has vitamin C, about 40 mg per 3.5 ounce serving. They have a similar protein content as beans and similar carbohydrate amount as wheat, which is about twice that of a potato. Chestnuts also have a high amount of sugar if they are allowed to ripen (also called curing.) Just-ripe chestnuts are low in sugar but as they cure their starch changes to sugar as much as eight percent. Curing takes three days to two weeks at room temperature depending upon the size of the nut. During this time the nutmeat shrinks some and the texture changes. Half water, they dehydrate quickly when picked which also lends them to long-term storage if dried properly. Average calories per fresh 3.5 ounce serving is 180. Eating a lot of them can cause gas. Edible or “sweet” chestnuts can also be eaten raw anytime but are usually eaten after curing and cooking. Before the American chestnut was wiped out it was a major cash crop with families taking wagon loads of them to trains in October for market in major U.S. cities.

Dr. Francis Porcher

The Native Americans also used the chestnut (Castenea dentata) medicinally. They used it for cough syrup, to treat sores, bleeding after childbirth, to relieve itching, for heart disease, colds, rheumatism, whooping cough, stomach troubles, fever, headaches, blisters, chills even as a baby powder. Francis Porcher, the well-known civil war doctor and botanist, reported in 1863 that the roots are astringent. He said a tea made from the root was good for diarrhea. When boiled in milk it was good for teething. He also said a decoction of the related chinquapin bark could be used like quinine. Chestnut trees had such a high amount of tannin that in 1900 they provided more than half the tannin used in the American leather industry.

Dwarf Chinkapin

There are several “Castanea” species in North America besides the chestnut. How many exactly is debatable because plant characteristics and name changes. Potentially there are the Dwarf Chestnut or Bush Chinquapin, Castanea pumila, also called Castanea alnifolia and Castanea nana. The Ashe Chinkapin, Castanea ashei also called Castanea pumila var. ashei. There is the Florida Chinkapin, Castanea floridana, the Alabama Chinquapin, Castanea alabamensis, the Ozark Chinquapin, Castanea ozarkensis, Castanea neglecta (which might be a hybrid between C. dentata and C. pumila) and “Castanea paupispina” which like the C. neglecta does not seem to have a common name. In fact, I doubted C. paupispina existed because I never saw it referenced any place except Wikipathetica. A learned reader wrote to tell me it is Castanea paucispina — spelled with a C not a P and is a variation of C. pumila in Texas. The misspelling on Wikipathetica has been copied throughout the internet. The proliferation of names is caused in part because the number of prickle density varies on the C. pumila vary leading to naming variations as different species. Castanea davidii, Castanea seguinii, Castanea mollissima and Castanea henryi are from Asia, Castanea creanata, Japan

William Willard Ash

Closely related to the American Chestnut, damage to the Chinkapins from the blight varied from at least some to badly. To my knowledge all of them have edible nuts but avoid those endangered. I’ve been fortunate enough to see one growing in North Carolina. Besides being spelled Chinkapin and Chinkquapin there is no great agreement on identification. C. pumila, for example, has also been called C. alnifolia, C. floridan, C. nana, and C. ashei. The Ashe Chinquapin a la Castanea ashei, is named for William Willard Ashe, 1872-1932, a prolific plant collector. He entered the University of North Carolina at age 15 in 1891. During his career Ashe wrote some 167 articles and named 510 species (including a couple after his wife, Margaret Henry Wilcox, Crataegus margaretta and Quercus margaretta.)

Chestnut Soup, recipe below

In early writing the chestnut is also called an “acorn” and is related to the Beech and the Oak. How the species got its eventual botanical surname “Castanea” is a bit of a linguistic conundrum. The American version was named after the European one. European chestnuts grew east of Greece — Pontus Greece now the western Black Sea area of Turkey — and were imported west to Greece in ancient times. There is a Kastania in Thessaly, Greece, which is the agricultural heartland of that nation and where the famous Meteora monasteries are located (churches on rock pinnacles.) Kastania has soil unlike most of Greece, rocky but acidic thus favorable to the chestnut. It was planted there and the town probably picked up the eastern name of the tree. It stuck with the town and the tree. The Greeks call the nut κάστανο (KAH-sta-no) and the tree καστανιά (kah-stah-nee-AH.) Note the shift in accent from the beginning to the end. The Bretons called it Kistinen, the Welsh, Castan-wydden, the Dutch, kastanje, and the French chataigne. Kastania in Greek became Castanea (kas-TAN-nee-uh) in Dead Latin (note the accent now in the middle.) Dentata (den-TAH-tah) means teeth because the leaves have large teeth. The English word “chestnut” also comes from the Greek word. Chestnut came from “chesten” which came the Middle English “chesteine”. That was from Old French “chastaigne” (with an S) which came from Dead Latin “castanea” which came from the Greek “kastania.”

Chestnut Weevil Larva, photo Ric Bessin

One interesting — some might say almost interesting — aspect of the chestnut blight was to make chestnut weevils nearly extinct. Without their preferred food Curculio sayi Gyllenhal and Curculio caryatrypes Boheman (small and large chestnut weevils) were close to being no more. But, folks started planting Chinese Chestnuts and saved the insects’ day. Like the weevils that infect acorns and palms they are edible raw or cooked. If you don’t want to find weevils in your chestnuts one thing you can do is soak the unopened chestnuts in 140 F. water for 30 minutes killing off the weevil eggs and or larvae. Picking up the fallen chestnuts immediately and cleaning up debris around the drip line of your chestnut tree are also important.

Longfellow’s Chestnut Chair

As one can imagine such an important tree made its way into much literature. Most famous is Longfellow’s The Village Blacksmith published in 1841. Under the spreading chestnut tree the village smithy stands… Longfellow, of Portland Maine, was the descendant of one Steven Longfellow who was a blacksmith and moved to Portland in 1745. The poem, however, was about Longfellow’s neighbor in Cambridge, Dexter Pratt. Years later an armchair was made from the very tree that shaded Pratt and presented to Longfellow. Stained black, it has a brass plaque that reads: “This chair made from the wood of the spreading chestnut-tree is presented as an expression of his grateful regard and veneration by the children of Cambridge.”

Henry Wardsworth Longfellow c. 1855

The chair is carved with chestnut leaves and blossoms while the seat rail is engraved with lines from the poem. I’ve been to the Longfellow house in Portland, growing up not 20 miles away. It’s in the up part of town but what they don’t tell you is it used to be down on the waterfront about a half a mile away where an iron fitting company named Thomas Laughlin, established 1836, used the real location to store products. There is a plaque there now, a rather sad stone stump closeted by a chain link fence in a drab industrial compound. Longfellow was not the only name of note to mention the Chestnut. Henry David Thoreau of Walden Pond, clearly a sensitive man, didn’t like throwing rocks at a chestnut to knock down its nuts. His journal entry of 23 Oct. 1855 says:

Henry David Thoreau, a chestnut nut, c 1856

“Now is the time for chestnuts. A stone cast against the trees shakes them down in showers upon one’s head and shoulders. But I cannot excuse myself for using the stone. It is not innocent, it is not just, so to maltreat the tree that feeds us. I am not disturbed by considering that if I thus shorten its life I shall not enjoy its fruits so long, but am prompted to a more innocent course by motives purely of humanity. I sympathize with the tree, yet I heave a big stone against the trunks like a robber—not too good to commit murder. I trust that I shall never do it again. These gifts should be accepted, not merely with gentleness, but with a certain humble gratitude. The tree whose fruit we would obtain should not be too rudely shaken even. It is not a time of distress, when a little haste and violence even might be pardoned. It is worse than boorish, it is criminal, to inflict an unnecessary injury on the tree that feeds or shadows us. Old trees are our parents, and our parents’ parents, perchance. If you would learn the secrets of Nature, you must practice more humanity than others. The thought that I was robbing myself by injuring the tree did not occur to me, but I was affected as if I had cast a rock at a sentient being with a duller sense than my own, it is true, but yet a distant relation. Behold a man cutting down a tree to come at the fruit! What is the moral of such an act?” Thoreau wrote more about the chestnut than any other tree in his journal.

By now you know there are European Chestnuts, and there were American Chestnuts. There are also “Horse Chestnuts.” Just to make things confusing the British call the edible chestnut the “Sweet Chestnut” where as the Horse Chestnut is just called Chestnut. They should have been consistent and called the Horse Chestnut the “Bitter Chestnut.”

Horse Chestnuts

And what of the Horse Chestnut? Should the issue ever arise don’t confuse sweet chestnuts with bitter Horse Chestnuts. The latter is a different genus altogether. And while there are reports that Horse Chestnuts, Aesculus hippocastanum (ES-ku-lus hip-o-kas-StAY-num) native to Greece, and Aesculus indica (ES-ku-lus IN-dick-ka) native to India, can be made edible I would do so cautiously. From India one report says: The seeds are dried and ground into flour… This flour, which is bitter… Its bitterness is removed by soaking it in water for about 12 hours. The bitter component gets dissolved in water and is removed when the water is decanted. Other references vary. One reverses the process by soaking the seed, drying, then grinding. Another just says boil the seeds for a long time. Removing the bitterness is important because the chemical(s) destroys red blood cells in humans.

What bothers me is that both Horse Chestnuts aforementioned — Greek and Indian — are not native to North America. They were planted ornamentals. Yet we are told by many reports that the American Indians ate them. It is possible but one would think the natives would have preferred the native chestnut that was not bitter and did not require processing. I think the writers are confusing Horse Chestnuts with Buckeyes which are native and in the same Aesculus genus. We have at least one authoritative report that the Indians on the west coast of America did indeed eat the seeds of Aesculus californicus (yes seeds, not nuts. Chestnuts have nuts but Buckeyes and Horse Chestnuts have seeds, a distinction perhaps more important to botanists than foragers.) According to Professor Daniel Moerman they pounded the seeds, leached them, then boiled them into a mush, eating it with meat. Others tribes roasted the nuts then ground them. The report from the Kashaya (Pomo) is quite specific:

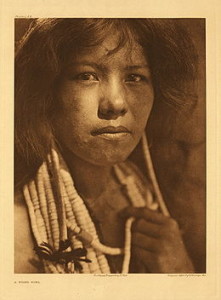

(Kashaya) Pomo girl; c. 1924, by Edward S. Curtis

“Boiled nuts eaten with baked kelp, meat, and seafood. Nuts were put into boiling water to loosen the husk. After the husks were removed the nutmeat was returned to boiling water and cooked until it was soft like cooked potatoes. The nutmeat was then mashed with a mortar stone. The grounds could be at strained at this stage or strained after soaking. The grounds would be soaked and leached a long time to remove the poisonous tannin. An older method was to peel the nuts and roast them in ashes until they were soft. They were then crushed and the meal was put in a sandy leaching basin beside stream. For about five hours the meal was leached with water from the stream. When the bitterness disappeared it was ready to eat without further cooking.”

At any rate unprocessed Horse Chestnuts are bitter. Edible chestnuts are sweetish. Edible chestnuts lay on their side. They essentially have a flat side and a round side and a pointed bottom. They are somewhat pyramidal. Horse Chestnuts are nearly round and sit vertically on their round bottom. In their shell edible chestnuts look like green sea urchins, horse chestnuts like green, spiny puffer fish.

Horse Chestnuts might have medical uses for edema.

Unprocessed — and perhaps even processed — Horse Chestnuts will make you sick. Symptoms are vomiting, loss of coordination, stupor sometimes paralysis. Few fatalities are reported. There’s about 17 reported poisonings per year in the United States caused by Horse Chestnuts. Juice from Horse Chestnuts, however, makes a good fabric bleach. Grind 20 seeds into 1.5 gallons. Let seep, stir then settle. Pour off the water using it for bleaching. Horse Chestnut starch was also used to make acetone during WWII. Now do you see why you should not eat Horse Chestnuts?

Hungarian Cream of Chestnut Soup or Gesztenye Leves

Ingredients:

- 12-14 ounces cooked and peeled EDIBLE chestnuts, finely chopped

- 4 tablespoons butter

- 2 parsnips, peeled and thinly sliced

- 2 carrots, peeled and thinly sliced on the diagonal

- 2 apples, peeled, cored, quartered and thinly sliced

- 2 leeks, white part only, thinly sliced

- 2 teaspoons sweet or hot Hungarian paprika

- 1/2 pound julienne-sliced leftover ham

- 5 cups chicken stock

- 1 1/2 cups whipping cream

Preparation:

- If using fresh chestnuts: Score the bottom or round side of one pound of chestnuts with an “X” and bring to a boil in a large saucepan of water. Reduce heat and simmer 30 minutes. Cool slightly and peel. Let cool completely before chopping finely. They can have the texture of soap.

- In a large saucepan or Dutch oven, melt butter and saute parsnips, carrots, apples and leeks, stirring occasionally, for about 10 minutes or until vegetables are almost tender. Mix in the ham, chestnuts, paprika and cook for one minute. Stir in the stock and bring to a boil. Reduce heat and simmer, uncovered, 20 minutes.

- In a medium bowl, whisk together cream and egg yolks. Temper this mixture with a few ladles of hot soup broth, whisking constantly. Then pour the tempered cream-egg yolk mixture into the soup, whisking constantly for one minute or until soup has thickened. Season to taste. Serve with sour cream, if desired.

Chestnut Nutrition

More controversial yet easy to identify is the two-leaf nighshade, or armatillo aka Solanum diphyllum. Suspected in the poisoning of children and cattle most references say it is not edible but I know several adults who nibble on the ripe fruit. They contain solanine. The problem with children is that they are small and tend to eat way too many berries where as adults eat one or two. (Cattle also eat stems and leaves.) Like sweet mild little tomatoes a few ripe ones do not seem to bother adults (avoid if you have an allergy to the nightshade family.) Possible symptoms of poisoning are nausea, vomiting, and gastrointestinal distress. Skin can also manifest redness, itching and a rash. Long term use can cause liver damage. The fruit has been used as a laxative and green fruit externally for ring worm. Ripe fruit is also toxic to dogs.

More controversial yet easy to identify is the two-leaf nighshade, or armatillo aka Solanum diphyllum. Suspected in the poisoning of children and cattle most references say it is not edible but I know several adults who nibble on the ripe fruit. They contain solanine. The problem with children is that they are small and tend to eat way too many berries where as adults eat one or two. (Cattle also eat stems and leaves.) Like sweet mild little tomatoes a few ripe ones do not seem to bother adults (avoid if you have an allergy to the nightshade family.) Possible symptoms of poisoning are nausea, vomiting, and gastrointestinal distress. Skin can also manifest redness, itching and a rash. Long term use can cause liver damage. The fruit has been used as a laxative and green fruit externally for ring worm. Ripe fruit is also toxic to dogs.