Pawpaw Panache

Finding your first pawpaw is a thrilling moment.

I can remember exactly where it happened and when. It was the summer of 1987 in Longwood, Florida, in The Springs, a gated community, along a nature walk. I happened to glance over and saw a pair of horribly stunted misshapen green pears. And as is often the case, once one gets the image of the plant in the head by meeting it in person, one begins to see them. Their most common appearance in Central Florida is along the margins of Interstate 4 in the Deland area, and of course, pastures.

Wild pawpaws fall in the same category as gopher apples. The woodland creatures usually find them first so you rarely see a ripe one. The fruit is edible straight from the tree but palatability varies. There are two general types. One ripens early and is large with flavorful yellow flesh; the other is often smaller, ripens later, and has white, milder flesh. You can also divide pawpaws another way, Florida and all others. Florida’s pawpaws tend to be shrubs, if not dwarfs. They are: Asimina obovata, Asimina incana, Asimina reticulata, Asimina longifolia, Asimina pygmaea, and Asimina tetramera. Farther north one can find the Asimina triloba reaching small tree height and in the coastal areas Asimina parviflora. While I have not personally tasted them all Dr. Daniel Austin in Florida Ethnobotany says he presumes they are all edible.

Pawpaws are rich in nutritional value, including high levels of vitamins A and C. The downside is they don’t ship or store well, on par with loquats. Also they severely nauseate some people, can cause a rash when handled, and the seeds contain a depressant. Incidentally, the fruit is the largest native North American fruit and is heavy on the protein side.

Pawpaws are also a little difficult to cultivate. In fact, they are really hard to cultivate. They need a lot of pampering for a few years to get them started, after that they are quite free of problems. They also attract a wide variety of butterflies. Those who champion the cause of pawpaws think that if they can persuade nurseries to pay more attention to the plant it can be a commercial success. It has few pests so it can be grown organically with little fuss. There might be even pawpaws on your grocery shelf in a few years. That would depend upon the lawyers.

Like all plants the pawpaw is a mini chemical factory. The Indians used dried pawpaw seed powder to control head lice and pharmaceutical preparations today still use pawpaws for that. The leaves are diuretic and the bark yields a strong fiber for cordage. It also belongs in a family of fruit trees that are suspected of inducing Parkinson’s Disease. That is currently being researched. Pawpaw has not been indicted but to a lawyer all that might be close enough to keep the fruit off the grocery stores shelves. You might have to forage for pawpaws or grow your own. Which reminds me, historically, the pawpaw was under cultivation by Indians east of the Mississippi when de Soto traipsed through in 1541. Chilled papaw fruit was a favorite dessert of George Washington. Thomas Jefferson planted some at his Monticello. I don’t recall of either dying from Parkinson’s.

As for its usual genus name, Asimina (uh-SIM-min-nuh) nearly any guess is as good as any other. My best deduction is the Indians called the bush Assimin (“min” in Algonquin means food, still found in “persimmon.” ) Assimin would be fine enough but then European languages and writers get involved. The early French inhabitants of Louisiana, called the fruit “Asiminer” from which we get the genus name. This is somewhat close to the Latin word for monkey, simia. That led to an early reference to calling the plant “monin” which was an old French word for monkey. That came from the Greek word for monkey, maimou. It changed through Latin into the romance languages as monin, mouninu, monnino, and monin. That leads folks to think the fruit had something to do with monkeys but I think it was just an assumption of one botanist who thought Louisiana French were referring to a “monkey plant.” Further, the pawpaw is North American and there are no native monkeys.

One Florida version is Asimina reticulata, (reh-tick-yoo-LAY-tuh) meaning the veins in the leaf have a net pattern. It can be found in slightly damp or occasionally damp areas. Another is Asimina obovata (oh-bo-VAY-ta) meaning egg-shaped leaves. It likes it dryer ground can grow twice as tall as the reticulata. The others are more or less reported, not the most common of shrubs. Locally pawpaws are rarely over four feet high whereas farther north the grow into trees. The A. obovata is listed as rare and the A. tetramera endangered.

One would think pawpaws would be a bit easier to explain, but no, and it also points to one of the problems of the cut-and-paste Internet. Many say pawpaw (or papaw or paw-paw) is a corruption of the American Indian word papaya, a version or cognate shortened by the Spanish. That’s not too bad, no great stretch there. And that it came originally from native Americans seems reasonable. Others, no doubt copying the same wrong site, note that it is Indian then make a huge leap across the Pacific and say it is from the Hindi language, you know, near China… and then younger folks wonder why older folks don’t trust the Internet…

Two aspects of the pawpaw I’ve found interesting is first it is in the Annonaceae family and closely related to magnolias though actually much older than the larger magnolias. The little ol’ pawpaw came first first. Next is that it is pollinated by carrion flies and insects attracted to fetid odors. Growers often put roadkill or rotting meat in their groves to attract the pollinating flies. Now there’s a tasty thought…

How to spell it… dictionaries are split, pawpaw, papaw… if you go back to the original it should be “papa” said pawpaw. In that regard papaw seems half-hearted. The USDA says pawpaw, Dr. Austin, ever sensitive to language’s influence on botany, went with pawpaw. Pawpaw eliminates mispronunciation, looks balanced to me and reflects the balanced sound the ear hears… always the musician…

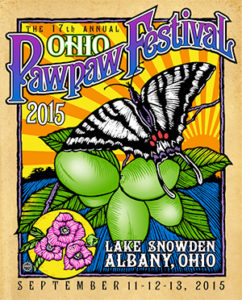

And in case you wondered since 1994, Kentucky State University http://www.pawpaw.kysu.edu/ has served as the USDA National Clonal Germplasm Repository, for Asimina species, as a satellite site of the NCGR repository at Corvallis, OR. There are over 2,000 trees from 17 states there on 12 acres at the KSU farm. Researchers evaluate the genetic diversity contained in wild pawpaw populations so that unique material can be added to the KYSU repository collection to be used in breeding. And for an unusual recreational and educational opportunity, visit the Annual Ohio Pawpaw Festival in September Lake Snowden in Albany, Ohio for three days of Pawpaw music, food, contests, art, history, education, sustainable living workshops and activities for the kids! http://www.ohiopawpawfest.com/ .

And in case you wondered since 1994, Kentucky State University http://www.pawpaw.kysu.edu/ has served as the USDA National Clonal Germplasm Repository, for Asimina species, as a satellite site of the NCGR repository at Corvallis, OR. There are over 2,000 trees from 17 states there on 12 acres at the KSU farm. Researchers evaluate the genetic diversity contained in wild pawpaw populations so that unique material can be added to the KYSU repository collection to be used in breeding. And for an unusual recreational and educational opportunity, visit the Annual Ohio Pawpaw Festival in September Lake Snowden in Albany, Ohio for three days of Pawpaw music, food, contests, art, history, education, sustainable living workshops and activities for the kids! http://www.ohiopawpawfest.com/ .

Green Deane’s “Itemized” Plant Profile

IDENTIFICATION: Shrubs or small trees, three to 40 feet, 15 common, evergreen in southern area, deciduous in northern area. Leaves alternate, simple ovate, smooth edge entire, length varies with species, flowers foul-smelling of rotting meat, single or in clusters, three large outer petals, three inner smaller petals, white to purple or red-brown. Fruit like cylindrical pears, misshapen, many seeds; green when unripe, maturing to yellow or brown, flavor similar to both banana and mango.

TIME OF YEAR: End of summer, fall

ENVIRONMENT: Rich bottom lands to rain-watered pastures, open areas, beside open areas. The two most common places I find it is at the base of tall pines or in cow pastures.

METHOD OF PREPARATION: Used like a banana, raw or cooked, as in baked desserts, ice cream, pastries, or in making beer. Don’t eat the skin and don’t eat the seeds. Chewed seeds will cause digestive problems, whole seed usually pass through. Try only a very little at first. Some people have a very several allergic reaction to pawpaws.