For The Edible Love of Krokus and Smilax

No, that is not a “Walking stick” insect. It is the growing end of a Smilax, a choice wild food.

There used to be a field in Sanford, Florida, near Lake Monroe, that was nearly overrun with growing Smilax every spring. I could get a couple of quarts of tender tips daily over a few weeks, enough for many meals. Cooked like asparagus or green beans, they are excellent, and also edible raw in small quantities.

The tip grows from the end of the vine and gets tougher as one goes back along the vine. Technically that is called

the meristem stage, that is, the growing part is almost always the most tender because the cells haven’t decided what it is they’re supposed to do, such as get tough and hold up the plant or create an odor or the like. The way to harvest smilax is to go back a foot or so from the end of the vine (more if it is a very large vine, less if small) and see if the vine snaps, breaks clean between your fingers. If not, move closer towards the growing end of the vine and try it again. Where the vine snaps and breaks is the part you can take and eat. Well-watered bull briers (Smilax bona-nox, SMEYE-laks BON-uh-knocks, that’s SM plus EYE) in a field or on a sunny tree can produce edible shoots a foot long and third of an inch through. Smilax is from the Greek smilakos, meaning twining but there is more to that story. Bona-nox means “good night” and usually refers to plants that bloom at night.) The Spanish called them Zarza parilla, (brier small grape vine) which in English became sarsaparilla, and indeed sarsaparilla used to come from a Smilax.

Often called cat briar because of its thorns, or prickles, Smilax climbs by means of tendrils coming out of the leaf axils. Again, technically, it is not a vine but a “climbing shrub.” No, I have no idea why someone thinks that’s important or how they can tell the difference. My guess is a vine has one stem and a shrub has several.) I am filing it under “vine.” Smilax are usually found in a clump on the ground or in a tree. They provide protection and food for over forty different species of birds

and are an important part of the diet for deer, and black bears. Rabbits eat the evergreen leaves and vines, leaving a telltale (tell tail?) 45 degree cut. Beavers eat the roots. Smilax also has a long history with man, most famous perhaps for providing sarsaparilla. The roots (actually rhizomes) of several native species can also be processed (requiring more energy than obtained) to produce a dry red powder that can be used as a thickener or to make a juice. Young roots — finger size or smaller — can also be cooked and eaten. While the tips and shoots can be eaten raw a lot of raw ones give me a stomach ache.

Medically, the root powder has been used to treat gout. A Jamaican species contains at least four progesterone class phytosterols. Some herbalists recommend that species for premenstrual issues. In 2001, a U.S. patent application said Smilax steroids had the ability to treat senile dementia, cognitive dysfunction and Alzheimer’s. A U.S. patent awarded in 2003 described Smilax flavonoids as effective in treating autoimmune diseases and inflammatory reactions. Note: These are patents claims in anticipation of clinical trials some distant day proving said claims by further research. So don’t start digging up Smilax roots for self-medication. A 29 Feb 2008 study suggest Smilax root has antiviral action and a 2006 study suggest it is good for liver cancer.

It should be mentioned that early American settlers made a real root beer from the smilax. They would mix root pulp with molasses and parched corn then allowed it to ferment. One variation is to add sassafras root chips, which gives it more of the soft drink root beer flavor. Francis Peyre Porcher wrote during the Civil War in the 1860’s “The root is mixed with molasses and water in an open tub, a few seeds of parched corn or rice are added, and after a slight fermentation it is seasoned with sassafras.”

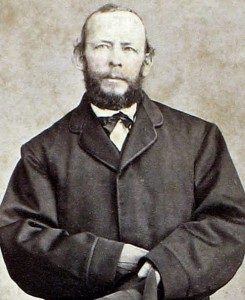

Can I take an aside here? Francis Peyer Porcher, 1824-1895, was a doctor, professor of medicine, and a botanist. Through his mother’s side, he was a descendant of the botanist Thomas Walter, author of Flora Caroliniana, the first catalog of the flowering plants of South Carolina, published in 1788. Peyer, as he liked to be called, was, as they used to say, well-to-do. He was professionally active in both fields — medicine and botany — when the American Civil War began. Because of the blockade of medical supplies he was ordered to write a field manual for doctors to help them find and make the drugs they needed in the

absence of supplies. His work, Resources of the Southern Fields and Forests, is still a reference and I have an ebook copy of it. It was so popular in his day that newspapers carried excepts of it. His effort was credited with helping the South prolong the war. We are fortunate to have two photographs of him, one presumably around war time and the other when he was again a professor and active in medical circles.

There are about 300 or more species in the genus Smilax and are found in the Eastern half of the United States and Canada, basically east of the Rockies. Fourteen species are found in the southern United States. Smilax gets its name from the Greek myth of Krokus and the nymph Smilax. The story is varied. Here’s one version: Their love affair was tragic and unfulfilled because mortals and nymph weren’t allowed to love each other. For that indiscretion, the man, Krokus, was turned into the saffron crocus by the goddess Artemis (because she, too, was having an affair with Krokus but as a goddess that was okay.) Smilax, actually woodland nymph, was so heartbroken over Krokus’ reduction down to a flower that Artemis took godly pity on her and turned Smilax into a brambly vine so she and Krokus could forever entwine themselves. There are far less poetic and less sanitized versions. Seems it was a popular story thousands of years ago with many variation and interpretations.

Oh, about that field in Sanford: A century ago it was a truck farm producing celery and other vegetables. Then it fell fallow growing Smilax. Now it’s an apartment complex. One last thing: Dried Smilax root can make a good pipe bowl, which is why the pipe bowl is called a “brier,”

Green Deane’s “Itemized” Plant Profile

IDENTIFICATION: A climbing shrub with tuberous roots, knobby white roots tinged with pink, bamboo like stems, more or less thorny, leaves varying with species and on the bush, tiny flowers, five slim petals, fruit round, green turning to black, one small brown seed. Some species have red fruit, edibility of red fruit unreported.

TIME OF YEAR: Starts putting on shoots in February in Florida, later in the season as one moves north. Seeds germinate best after a freeze.

ENVIRONMENT: It grows best in moist woodlands, but can tolerate a lot of dry and is often seen climbing trees. Left on its own with nothing to climb it sometimes creates and brambly shrub. Thicket provides protection for birds.

METHOD OF PREPARATION: Beside making sarsaparilla, the roots can be used in soups or stews, young shoots eaten cooked or in small quantities raw, berries can be eaten both raw and cooked, usually are chewed like gum (avoid the large seed.) Pounds of roots to pounds of flour is a 10 to one ratio.