Munching Cornus canadensis/unalaschkensis

Discussing things little ears shouldn’t hear, they barely interrupt their conversations to pick a low Bunchberry from off the forest floor. It was a natural action, like picking a flower while one walked.

“They” were my mother and grandmother, walking along that endangered relic called a woods road. I shall try to forget that it was more than a half a century ago. As they munched on Bunchberries my dog “Sister” and I terrorized the woods. Though not much bigger than my setter/collie I learned the difference between the Bunchberry and Doll Eyes, one edible, one deadly.

There was a continuity there which has been lost for most people. My mother, Mae Lydia Putney, picked Bunchberries because her mother, Abby Ora Blake, picked them, and my grandmother picked them because her mother, May Eudora Dillingham, picked them and no doubt learned it from her mother Abby Warren. (In most cultures women tend to be the foragers, men the hunters. It’s my father’s side that’s Greek.) And somewhere back in that line they learned it from Native Americans, and they learned it the hard way over the millennia. Somewhere along the line we stopped appreciating or learning the experiences that were passed on, whether about plants or life.

I once had a friend in the mid-1980s tell me she was certain no one in her family ever collected wild foods. As proof she said her father, John White — now there’s a genealogical nightmare — was born in New York City in 1900. Mr. White, whom I met, had my friend when he was 50. “And his parents” I asked? They immigrated from rural Ireland around 1870. “So” I said, your grandparents were foragers. In one generation the knowledge, habit. and mindset can be lost.

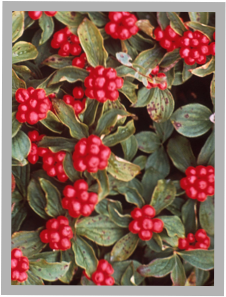

The Bunchberry, Cornus canadensis, (KOR-nus kan-uh-DEN-sis) has its champions and detractors. The particular say it has no taste. I knew two women who didn’t miss a single one. The Inuit saved them by the bushel basket for winter. For such a humble plant it has many names: Dwarf dogwood, bunchberry dogwood, Canadian dwarf cornel, pigeonberry, squirrelberry, low cornel, ground dogwood, bunchplum, creeping dogwood, cuckoo-plum, frothberry, dogberry, crowberry and crackerberry. The last two are actually the same. “Cracker” comes from “crake” and that means crow. As if that’s not enough names it is also called the puddingberry. Why puddingberry? It was the habit in New England cooking to add a few bunchberries to a pudding to add color and help it jell. Seems the little berry has a good dose of pectin in it.

The Bunchberry is a perennial sub-shrub and is the smallest member of the dogwood family. Dwarf dogwood is native to a broad area extending west from southern Greenland across Canada and the United States the south along the Rocky Mountains. You also find it in northeastern Asia. It likes moist well-drained forest soils and can often be the dominant ground cover. It will not grow where the summer ground temperature exceeds 65F.

The “flowers” of dwarf dogwood — like most dogwood — aren’t what they appear to be. The four white “petals” are bracts that look like petals. Clustered in the center, like the berries will later be, are many tiny white to purplish flowers. They are pollinated by flies and bees attracted by the bright bracts. In late summer a bunch of round red fruit appears giving the plant its name. Their texture is mealy and each has one seed, occasionally two. While the Inuit froze the Bunchberry other natives preserved them in bear fat. The berries make an excellent jelly.

What the scientific name means is a bit of debate. Canadensis means northern North America. Cornus means horn which can mean a wind instrument or hard. The dogwood is known to make stiff skewers and dogwood is from Dag where we also get the word dagger. Oh, they recently changed its name to Cornus unalaschkensis, KOR-nus un-uh-las-KEN-sis, named for Unalaska, one of the Aleutian Island. It looks like Un-Alaska to me rather than un-uh-las-KEE-sis.

As an aside, think of the comic character, Dagwood Bumstead. “Dagwood” means “luminous forest” but was corrupted to dogwood. “Bumstead” was originally Bumpstead and means a “place of trees.” So his name mean place of bright trees (and when dogwoods are in blossom) they are luminous.

A variety of birds and moose like the bunchberry, which is the fastest flower in the world. Oh, you doubt that. Well, read on.

Bunchberry found to be fastest plant

The Independent, London 12 May 2005

By Steve Connor

Botanists have identified the fastest moving plant in the world ” the bunchberry dogwood of North America.

Tests have shown that the petals of the plant’s tiny flowers can move at 22 feet per second when they open with an explosive force. The bunchberry dogwood ” Cornus canadensis ” grows in dense carpets in the vast spruce- fir forests of the North American taiga. The petals explode open to launch pollen an inch into the air, a study at Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, showed. The pollen is ejected to 10 times the height of the small plant so that it can be carried away on the wind.

The scientists say in Nature: ‘Bunchberry stamens are like miniature medieval trebuchets ” specialized catapults that maximize throwing distance by having the payload [pollen in the anther] attached to the throwing arm [filament] by a hinge or flexible strap.’

Green Deane’s “Itemized” Plant Profile

IDENTIFICATION:

Spreading subshrub terminal whorls of oval, lance-shaped leaves. Tiny bunch of flowers over four white bracts above six green dogwood shaped leaves. Flowers in May and June, sometimes in autumn.

TIME OF YEAR:

Bunch of red berries, late summer to early fall

ENVIRONMENT:

Northern forests, well drained soil, ground never warmer than 65F or lower than -28F

METHOD

Out of hand, or made into jelly.

HERB BLURB

Dogwood bark is a substitute for cinchona bark, the source of quinine, for treating Malaria