Real spruce gum is not easy to chew. It is not soft or sweet. Hard and crumbly is more accurate along with pieces of bark and bits of insects. But if you have good teeth and patience it will in time become a stiff gum. And if you leave it on your bedpost over night the gum turns hard and crumbly again.

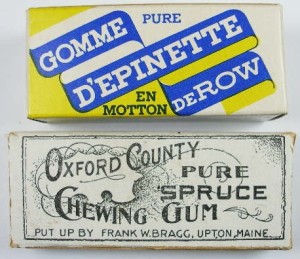

There was a time in America when you could buy spruce gum in almost any store, like other kinds of gum today. In fact it was the first gum sold in America. There were several brand including American Flag, Yankee Spruce, 200 Lump Spruce, and Kennebec. The original commercial version was State of Maine Pure Spruce Gum made by John B. Curtis and his brother in Bradford, Maine, about 30 miles north of Bangor. There was significant demand for debris-less gum and the brothers’ business thrived. Later they added beeswax or paraffin to the gum to soften it and expand their line. They moved their company to Portland around 1850 and had some 200 employees. From the mid-1800s to the early 1900s some dozen and a half companies were producing spruce gum. “Pickers” got paid up to a dollar per pound depending upon the quality. The technique was not unlike collecting pine pitch for making turpentine except the pitch was hard not soft. Some pickers collected thousand of pounds per year. Up until my college years one could still by soft spruce gum from L.L. Bean. (I grew up four miles west of the main store.) L.L.Bean no longer carries the product but the Naturallist does, by the box, as does Damn Yankee Company. Or, you can make your own. First you need the tree.

Naturallist sells hard and soft spruce gum.

The Black Spruce, Picea mariana, is found in all of Canada, New England, and the mid-Atlantic States down to Pennsylvania. It is also found in the northern parts of the Great Lakes states excluding Indiana and Ohio. Some report you can find it in the higher, cooler areas of the Appalachians as far south as North Carolina. Red Spruce has also been used to make spruce gum and in fact you can use any spruce as long as it is in the Picea genus. Black Spruce was, however, considered the best source but that is debatable.

After finding a spruce you look at the trunk. Where ever there is damage to the bark there should be lumps of spruce sap, id est resin, or pitch. Breaks in the bark are caused by a variety of things from bear clawing to wind damage. The tree tries to repair the damage by covering it with sap. Some of the sap will be soft. We’re not interested in that for gum though it has other uses. It takes two to four years for the sap to harden into lumps, which is what we want. The texture can vary according to how dry it is. The color ranges from cream to yellow, pink to brown. It used to be said that “amber” resin was the best but I think that is folk lore on loan from maple syrup where “amber” is the best. The resin I always collected — by chance not choice — was dark amber which in turn made a light pink gum. Visiting several trees over a couple of hours can get you about a pound of hard resin. You don’t need that much. A small amount will do for experimenting.

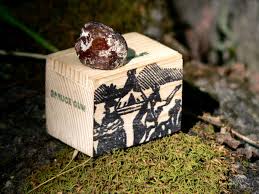

Spruce resin can also be used to waterproof boats. Photo by Jamaka

The first step is to reduce the amount of woody pieces in the resin, such as bark and twigs. To do this you put everything in a heavy cloth (a canvas bag works well) and pound it until the resin has the texture of sand. Dry resin crumbles easily leaving the woody bits to be removed by hand. Soft resin only makes a gooey mess. After crushing a small screen works well in cold weather to separate the woody bits if you have good dry resin. Step two requires some preparation. You will need a shallow metal pan for the hot resin to cool in. This pan needs to be wrapped in cloth which you will pour the hot resin through, further filtering it. You also need, preferably, a tall skinny pot to heat the resin in. It is best to use an old pan for this because you won’t be able to get all the resin out of the pot so the pot can only be used for making spruce gum. (I learned this short-coming by using one of my mother’s favorite pots the first time.) The small brass pots used to make espresso by hand are good for this. A cast iron pan too pitted for frying works well, too.

Put your granulated resin in the pot and add enough water to makes a slurry. Then heat slowly over low heat (remember, resin can catch fire easily or burn you badly if it gets on you while hot so be careful. This not a kid’s job.) In time the hot water melts the resin which will float on top. When all the resin has liquified pour it quickly through the cloth into the cooling pan. Some resin will stay in the pot which you can melt next time. It takes about a half hour for all the resin to harden. When it does remove the cloth and pour off the water. A tap on the bottom of the pan should dislodge the resin. Now you can break it up into chewable amounts. Store them in a dry place after sprinkling them with cornstarch to keep the pieces from sticking to each other. Confectionery sugar might be a good choice, too, but I don’t know as I’ve never had a sweet tooth.

Now comes the hard part. Spruce gum is brittle at first and will shatter into tiny pieces in your mouth. You must keep chewing the little pieces and keep collecting them into one piece. As the gum warms and is ground smaller it will turn into a piece of gum and stay that way as long as it is warm. A large breath of winter air, however, can harden it, so keep it warm. The taste is… well… sprucy but it does moderate over time, harsh at first, almost sweet after several hours of chewing. And if you swallow it, it should cause no problems.

Damn Yankee Company also sells bite size pieces.

With all that said, I am sure the natives did not go to all that bother to melt the resin down and clean it just for gum. It’s a chore with modern equipment and would have been very difficult a thousand years ago when pots were hard to come by. However, the heated sap does make a brittle waterproof glue so maybe when treating their birch bark canoes they chewed some of the resin. Personally I think they did what I mostly did as a kid: I just took a lump off the tree, crushed it up with my teeth, spit out the woody bits as best I could, and just chewed. Your teeth will stick together for a while and the pitch flavor is intense but it does turn into gum that way.

Pickers put spruce scrapers on pole to extend their reach. Photo by Adirondack Almanacs.

Not only did the Native Americans show the colonists how to harvest the resin they also used the soft pitch for sore and skin problems. It was also used to make cough syrup which is not that unusual of an idea in that pine pitch can be used the same way, usually mixed with honey. Below are some modern medical references testing the sap. Lastly, spruce gum even found its way into love. Many a picker was also a woodsman of differing trades, such as lumbermen or sawyers. They would often work all winter in the woods away from their sweethearts. Many of them would make gifts of little boxes with sliding tops to store spruce gum in called gum books. And, of course, they were also full of choice spruce gum. However, kissing someone who has been chewing on spruce gum would seem to me to be more along the lines of kissing a Listerine bottle than the sweet lips of poetry and romance.

Medical Studies

Sipponen A, Jokinen JJ, Sipponen P, Papp A, Sarna S, Lohi J. Beneficial effect of resin salve in treatment of severe pressure ulcers: a prospective, randomized and controlled multi-center trial. British Journal of Dermatology 2008;158:1055-62

Sipponen A, Rautio M, Jokinen JJ, Laakso T, Saranpä P, Lohi J. Resin salve from Norway spruce – a potential method to treat infected chronic skin ulcers? Drug Metabolism Letters 2007;I:143-5

Rautio M, Sipponen A, Peltola R, Lohi J, Jokinen JJ, Papp A, Carlson P, Siponen P. Antibacterial effects of home-made resin salve from Norway spruce (Picea abies). APMIS 2007;115:335-40

Sipponen A, Jokinen JJ, Lohi J. Resin salve from the Norwegian spruce tree: a “novel” method for the treatment of chronic wounds. Journal of Wound Care 2007;16:72-74