A farmer’s headache is not necessarily a forager’s delight.

Palmer Amaranth (Amaranthus Palmeri) has been a foraged food for a long time. It was used extensively by the native American population with at least seven tribes preparing it a wide variety of ways. More on that in a moment.

Amaranth, in general, is a good wild food. It occupies the middle ground between excellent and poor. When collected very young Amaranth is a dietary analogue to spinach, which is a relative. At the meristem stage, still young and tender because the cells are still growing, it’s a tasty green usually boiled. Later it becomes a source of grain. These stages, however, are dynamic, changing and they change at different rates with different species of amaranth. Some amaranths stay more palatable longer than others. More so, depending upon growing conditions, amaranth can also accumulate high levels of nitrates and oxalates making them less than desirable to eat, for you or livestock.

Palmer Amaranth doesn’t stay young and tender too long. It converts CO2 into sugars more efficiently than corn, cotton or soybean. This allows for rapid growth even when it’s hot and dry because it also produces a large taproot that is studier than that of soybeans or corn and can penetrate hard soil better than cultivated crops, read it can reach water and nutrients other plants can’t reach. Under ideal conditions, Palmer Amaranth can grow several inches per day, upper left. The species also has a rugged stem to support that growth and height.

Palmer Amaranth Pulled From A Peanut Field, photo by Rome Etheredge, extension agent, Seminole County, Georgia.

If you think Palmer Amaranth is already a Botanical Bully then consider this: It is unusual for an amaranth in that it has male and female plants which greatly aids in distribution and ability to adapt. It can also produce half a million seeds per plant. Every seed is a chance to defeat Genetically Modified Organisms, which are quite expensive to develop. When you consider Ma Nature produces million of Palmer Amaranth plants every year that adds up to perhaps billions of chances annually for her to roll a winner, virtually for free. And that’s exactly what happened. Palmer Amaranth developed a resistance to the weed killer glyphosate and became a superweed. That resistance is costing literally millions of dollar in lost agricultural crops. It “single-plantedly” ruined large farming operation in southern Georgia. That has lead to a lot of hard feelings and finger pointing.

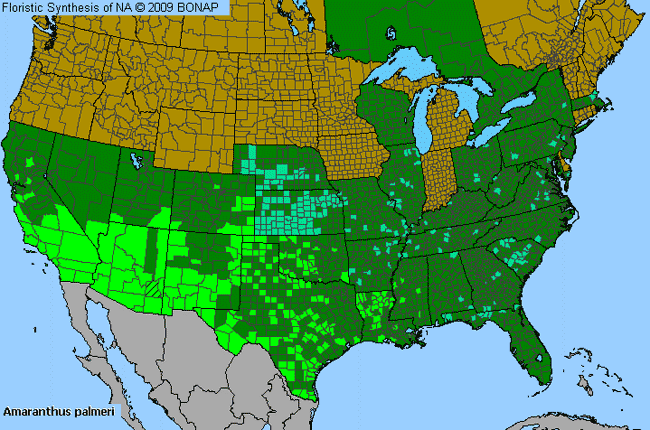

With the help of a nescient media and the no-quality-control Internet the issue is putting farmers and foragers on opposite ends of the nasty rumor mill. More so, what is playing out in Georgia can and will happen elsewhere because resistant Palmer Amaranth is now found in some 20 states. Also, the resistance is expected to spread to other amaranth species plus other edible weeds are developing resistance which brings new meaning to the phrase “seeds of change.”

Threatening perhaps 500 acres of soybean and cotton in 2004 Palmer Amaranth by 2010 was affecting up to two million acres in the lower half of Georgia. While that put thousands out of work on the other side of the garden row were foragers saying ‘not all is lost, all you have to do is eat the weed.’ It was inevitable that Internet sites began saying experts were advising people not to eat Palmer Amaranth because the resistance, a kind of botanical doomsday scenario from a grade B movie. ‘Palmer Amaranth killed our crop and it will kill you too.’ That led to a lot of email to me and we all get too much email. I thought getting to the nitty gritty of it all would in the long term help ease my email inundation.

The person most often cited as saying the resistant amaranth is not edible is Dr. Stanley Culpepper, associate professor, University of Georgia, and Extension Agronomist. Not so. I contacted Dr. Culpepper personally regarding the edibility of Palmer Amaranth and asked him about it. His view is quite different than what’s rumored on the Internet.

“If one decides to eat Amaranthus Palmeri,” Dr. Culpepper said, “there will be no difference in its taste or nutritional value if it is resistant to glyphosate or not. To date, we have not documented any change in the biological aspects of plant growth or reproduction with regards to resistance.”

That’s quite straight forward. Where in that statement do you read Palmer Amaranth is not edible? No where. Dr. Culpepper’s post doctoral assistant, Dr. Lynn Sosnoskie, who was also kind enough to contact me, added that there shouldn’t be any difference between the resistant and non-resistant plants though that was not specifically tested by researchers. More so Dr. Sosnoskie said that unless one actually tested a plant for glyphosate one could not readily tell the difference between a resistant and a non-resistant plant. However Dr. Sosnoskie did add an observation of interest to us forager. She said Palmer Amaranth tends to grow mostly on highly managed agricultural land and that land has “likely been treated with insecticides, fungicides, and/or herbicides.” That is important.

Thus, and this is my opinion not Culpepper’s or Sosnoskie’s so blame me not them: If there is an issue with Palmer Amaranth edibility it might not be the plant or glyphosate resistance per se but that of an unmanaged plant growing on highly-treated agricultural land. Unlike a commercial crop grown on such land with supervision and exact timing a wild plant might be on such land too long, under the wrong conditions, or harvested at the wrong time. I can see how that might affect edibility particularly with amaranth’s penchant for taking up too much nitrates and oxalates. Again, that is my opinion not Culpepper’ or Sosnoskie’s.

The philosopher William James, and brother to novelist Henry James, always insisted there be a practical side to everything, including philosophical notions. A hard-core New Englander he called it “take home change.” What’s the “take home change” of all this? Palmer Amaranth is edible but not the best of the amaranths. There is no evidence the edibility of Palmer Amaranth is different if it is “resistant” or not. It’s fast growing and does not stay young and tender very long. It can accumulate elevated levels of nitrates and oxalates and would probably do so on improved land, read land that is fertilized a lot such as agricultural land is. Amaranth on unimproved land usually has safe levels of nitrates and oxalates.

The foraging advice of “just eat” Palmer Amaranth does not take into consideration the environment. As my readers know I champion my I.T.E.M. system of foraging and that includes E, for environment. In this case the edible plant in question usually grows in a highly fertilized if not chemicalized environment (vs the poor soil it usually inhabits.) This increases its chances of having higher than normal nitrate and oxalate levels, and probably other things, too. You have to take that inconsideration as part of your foraging decisions. I personally doubt some young and tender Palmer Amaranth plants are much of a problem. But, older plants could be and adult plants might sicken livestock. Also, the problem should lessen with time if the fields lie fallow. It’s an environmental issue more than a genetic engineering one for us foragers. Now you have the accurate information and reasoning you need to make an informed foraging decision regarding Palmer Amaranth in agricultural fields in Georgia. That said, what about Palmer Amaranth?

Amaranthus palmeri aka Carelessweed, is one of 60 to 70 species in the genus, depending upon who’s counting. Palmer Amaranth is a very competitive native now found in 30 states but not reported yet in Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Delaware, Michigan, Alabama, Hawaii, Indiana, and the northern tier states from Iowa north and west.

The Cocopa, Mohave, Navajo, Papago, Pima, Pima Gila River and Yuma tribes all used the Palmer Amaranth for food. Their methods varied greatly including: Fresh plants baked and eaten; leaves boiled as a green; leaves cooked, rolled into a ball, baked and stored; leaves dried then stored for winter; leaves boiled and eaten with pinole; seeds ground into a meal; parched seeds ground then chewed for sugar; seeds parched, sun dried, cooked, stored for winter.

Amaranthus (am-ah-RAN-thus) is from Greek means unfading, or evergreen. Palmeri (PALM-er-ee) was named in 1877 after Edward Palmer, plant explorer extraordinaire. Palmer was the right person in the right place at the right time. When Europeans first landed in the new world they were very interested in plants but didn’t record much about how the natives used most of their plants. By the time the white man was pushing west to California a different attitude prevailed. This is why in most ethnobotanical references we know far more about what the Western natives did with plants than the Eastern natives. And one of the reasons why we know that was Edward Palmer, 1829-1911. He collected over 100,000 specimens and discovered some 1,000 new species. Palmer also visited local markets to get plants and study how they were used helping to found modern ethnobotany.

Green Deane’s “Itemized” Plant Profile: Palmer Amaranth

IDENTIFICATION: Amaranthus palmeri: Long dense, compact terminal panicles to 1.5 feet, tall — six feet — with alternately arranged leaves, petioles longer than the leaves. The leaves of Palmer Amaranth are also without hairs and have prominent white veins on the under surface. The male flowers have highly allergenic pollen.

TIME OF YEAR: Flowers summer and fall

ENVIRONMENT: Agricultural land, disturbed areas, riparian locations, desert, uplands.

METHOD OF PREPARATIONS: Young leaves, young plants, growing tips boiled, baked or dried. Seeds used as grain, parched, roasted, or ground into flour.