Arisaema triphyllum: Jack and Jill and No Hill

For a little plant there’s a lot to write about with the Jack-In-The-Pulpit. Where does one start? What does its name means? How about its ability to change sex? And of course the misinformation about it on the Internet. Let’s cover it all.

The name “Jack” has many meanings. One is a nick name for John. Another means “male” as in jackass. It has also be used for sailor (Jack Tar) Steeple Jack (laborer) Jack of all Trades (a man who does nothing well) and Jack-O-Lantern who used to be the fellow who went through town carrying a lamp while crying out the time and curfews. Jack has also been a common term for the Devil. And so it fits with Jack-in-the-pulpit, a little plant with a devil hiding and mighty toxic sermon if not prepared correctly.

As for sex… the plant is a switch hitter, Jack sometimes, Jill sometimes. And as foragers we should know the difference because the edible part of the plant — when prepared correctly — differs between he and she.

Jack-in-the-pulpits are perennials and grow each season from a corm, kind of like an onion. They can live to 100 years old. The shoot will have one stem or two. Each stem usually has three leaves if we are referring to the Arisaema triphyllum. The pulpit, or spathe, is green, with white, brown or purple stripes. The minister, or spadix, is usually a pale cream spike inside.

These plants are either a Jack or a Jill. If you open the flower and look inside the female has a developing cluster of tiny green berries. The male does not. What difference does it make?

If the corm is packed with nutrients the plant will produce a spathe for a female flower with, usually, two stems for a total of six leaves. If the corm is young or depleted it will produce a spathe for a male flower, one stem and three leaves. This is not always true but is a common display.

If you find a female plant early in the season this tells you there should be a good size corm below — up to three years of storage in fact. If you find a male at the beginning of the season that tells you it is either a juvenile or was a female last year and the corm smaller. So you don’t want to dig up the male early in the season but rather late in the season after he’s had several months to collect up energy in the corm. You don’t want to dig up the female late in the season but rather early. Exceptions: Very young plants with no corm tend to produce one stem and are small. In fact, most male Jacks are under 14 inches tall. Most Jacks over 14 inches tend to be Jills.

To recap: If the plant has one stem and three leaves it’s usually a male, two stems and six leaves a female. Generally he has bigger corms at the end of the season, she has bigger corms at the beginning of the season. You can also look down inside the spathe and tell if it is a he or a she. She will be making green bumps that will be future red berries. And what of that corm that the Indians called the “fire ball?”

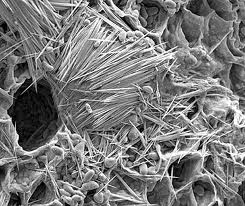

In its raw state chewing on a corm will “burn” your mouth and swallowing it will poison you, while painfully probably not fatally though you may have a rash of kidney stones, which can make death seem a pleasurable alternative. The offending chemical is needle-shaped calcium oxalate crystals called raphides (RAF-ee-dees.) They sting painfully. If you manage to swallow untreated corms the raphides can “precipitate” in your kidneys, which is a fancy word for clogging them up. So don’t try to eat the corms raw. Don’t eat them dry if they produce a burning sensation in your mouth. The goal is to make them burn-free before consumption.

Calcium oxalate, at the very least, causes intense discomfort. Tiny amounts can create the sensation of burning. In some cases it can lead to swelling of the throat and closing off of air. In larger doses, it can cause severe digestive upset, convulsions, coma, and death. Recovery is possible, but permanent liver and kidney damage can happen. The worst part is the effect even in the mouth can be delayed for a few minutes. This is why you must always try only a little after preparing it, chew it, spit it out, and wait ten minutes or more.

Scores of Internet sites that copy each other say boiling the corms makes them edible. That is very misleading. When I read that I know the writer has never boiled a corm then tried it. I have boiled potato chip thin slices up to six hours and still had them burn some. Maybe at 12 hours, or the two day mark they stop burning, but for a third of an ounce of starch it is not cost effective.

I traced the boil comment back first to 1916 in an article by National Geographic Magazine, then to a Scottish book in 1875 called The Wealth of Nature, our food supplies from Nature. In the article about “Common American Wild Flowers” it talks on page 590 about “boiling the bite” out of the corms. But the writing style is affected and I think the phrase was used for its assonance sound than its accurate information.

The 1875 book, referring to the family in general, says an “Indian plant” can be roasted or boiled. There are also some references in other places to boiling the corms and then drying them. Someone may have presumed boiling was making them edible and drying was for storage. At any rate, the mistake is entrenched. Boiling for a day or more may work but I know for absolute certainty several hours does not do it. Drying is a far better choice.

Many “edible” plants have calcium oxalate and boiling them doesn’t get rid of it for them either, wild taro roots in Florida, for example. Why should it be different for Jack-in-the-Pulpit? Dry heat breaks down the calcium oxalate. Short-term moist heat does not. Let me be succinct: Slice thin then air dry for three months or more. Slice thin and dry in a slow oven for three to seven days or so or in a food dehydrator. One other option is to put them in the microwave.

While my results varied I have made some sliced corms edible after three minutes in my microwave, but some were still burning at five minutes, and 10 minutes tends to incinerate them, unless whole. Clearly air drying is the cheapest and produces the sweetest product. Nuking them produces a cooked nutty flavor but they go from edible to burnt crisps in seconds.

I’ve also sliced and dried them in my solar oven which reaches around 325F. It takes about three days of trying, 15 hours, to get them edible, and little energy is used. And all those times are precautionary times. Your times can certainly vary so carefully try your slices before consuming. Here’s how you do that.

To test them: Chew a quarter-inch square piece on one side of your mouth for a full minute then spit it out and wait ten minutes. And I mean chew for a minute and I mean wait ten minutes and I mean one side of your mouth (to limit the area that burns.) The effect can be quite delayed. If the calcium oxalate is still present it will make one side of your mouth burn, and your tongue and lips. That can last up to a half an hour or so. If no burn, try a bigger piece the same way. If no burn then, you’re ready to go. You can eat the dry chips as is, or grind them up as a flour. If you air dried them they can be used as a thickener. If you dried them at over 150F they can be used as a flour but not as a thickener because the starch will have already been cooked.

In a 1906 book (Studies of Plant Life in Canada by Catherine Parr Strickland aka Mrs. C.P. Traill — yes, two l’s) she refers to a European relative of the Jack-in-the-Pulpit, the larger Arum maculatum, also called Cuckoo Pint. They were dried thoroughly then pounded or ground then tossed into water where the starch settled, a similar process to extracting starch from the cattail root. That starch was then pounded or ground a second time and put in water again. This was done until the visible impurities were all removed (the calcium oxalate already removed by drying.) Then the water was poured off and the starch allowed to dry. She reported a peck of roots created a pound of starch. That starch was one time called Portland Sago, from Portland Island in Dorsetshire, England. It was used like saloop, a drink popular in England in the 17th and 18th centuries before coffee and tea were imported. Ground A. maculatum powder was added to water until it thickened. Then it was sweetened and flavored with orange flower or rose waters. Because it would thicken it was also used as a substitute for arrowroot. However, the powder used for saloop and as an arrowroot substitute was from dried not roasted corms since roasting would cook the starch rendering it not useable as a thickener (the same issue with acorns. To use them as a thickener or binder they must be processed without cooking, that is, under 150F.)

Catherine Parr Strickland then returned to North America in her book with the comment: “When deprived of poisonous acrid juices that pervade them, all our known species may be rendered valuable both as food and medicine; but they should not be employed without care and experience.”

Now, what about the berries? I have not tried them and they are listed as toxic, probably for the same reason the corms are. There are some references that say the totally dried berries are edible but I have not tried them so I cannot recommend them.

Besides careful humans the only other creatures to find food from the plant are Wild Turkeys and Wood Thrushes who eat the red berries. Those berries, by the way, were used by Indians to make red dye. (And early settlers used the starch in the corms to starch their clothes.)

The plant, for all its warnings, is also a pain killer, as reported by Dr. Daniel Austin in his book, Florida Ethnobotany:

“When I was a professor in Florida, a mother and her young son came to me for “advice” about a science project that the boy was doing. He had apparently discovered independently that juice from the live plants applied to wounds stopped the pain. Since he was still in grade school, it seemed unlikely that he had scoured the old literature and learned that the natives of North America used the sap in the same manner. Regardless, he was doing an experiment that involved getting as many volunteers as possible to prick their finger with a needle and then apply juice directly from the plants. I, too, became one of his subjects with plants that they had imported from New England. We dutifully cleaned the instruments, drew the blood from the end of my finger with a needle, and then applied the juice. The pain stopped immediately upon contact with the liquid. They told me that each person they had tested had exactly the same reaction….”

The scientific name for my local Jack-in-the-Pulpit is straightforward. Arisaema (ar-ih-SEE-muh) is a combination of two Greek words, “Aris” or “aridos” which was a name used by Pliny for a small herb thought to be in this family, and “hiama” or “haimatos” meaning blood as some of the species have red/purple spots or stripes. Triphyllum (tree-FIL-um) means three leaves. There is a bit of a botanical argument where there is one species and variations or three species, or more. Incidentally, the A. dracontium (dray-KON-tee-um) is used the same way. It has a long tip to its spathe and a different arrangement of leaves.

Green Deane’s “Itemized” Plant Profile

IDENTIFICATION: A flap-like spathe curves over the top of a funnel-shaped spadix. It can be green, purplish or striped. Leaves are long, ovate, usually three per stem. Fruit inside spadix looks like a cluster of little eggs, green at first later scarlet red. Corm is walnut-sized or larger, can have brain-like folds..

TIME OF YEAR: While available year round, gather in the fall or early spring or when dormant. Store in damp sand.

ENVIRONMENT: Likes moist forests and shade, bottom land, damp soil but not waterlogged.

METHOD OF PREPARATION: Only dry heat degrades the calcium oxalate crystals efficiently. Slice thin, dry for three months (in the sun is even better) or in a slow oven or dehydrator for about five days. In my experience boiling takes in excess of eight hours to make them approaching edible. Once cleared of the acid the corms can be used like arrowroot or flour depending on how hot it was heated.