Skunk cabbage in springtime

The first eight years of my formal education was spent in one-room school houses without running water. The 7th and 8th grade-school house was in the center of Pownal, Maine. There was a pine-covered hill behind it to the east no doubt over a ledge, and a gully to the north of it. There I saw skunk cabbage and trilliums in early May, both of which smelled like Budweiser beer (which is an adult, hindsight observation as neither of my parents drank.)

Young skunk cabbage. Photo by Derek Ramsey

I was in that particular school house in the early 60’s including November 22nd 1963. A decade earlier Merritt Fernald of Maine was writing about skunk cabbage and apparently there was some ethnic controversy about it. He wrote on page 118 and 119 of Edible Wild Plants of Eastern North America “The roots of skunk cabbage have had a repute among the eastern Indians as a source of bread, in regions where the plant thrives the roots are abundant but difficult to dig; and obviously, for many reasons, only an enthusiast will try to secure them. It is probable that drying or baking before final use will dispel the acrid properties, as in Peltandra and Arisaema, but our own experience show that three weeks of drying is insufficient to dispel the peppery quality. The bread made from the flour dried for three weeks is palatable, having a suggestion of cocoa flavor, but a few minutes after it has been eaten the mouth stings with the perculiar burning and puckering sensation familiar to all who have tasted the fresh root of the Jack-i-the-Pulpit. One average root gives about half a cup of flour.

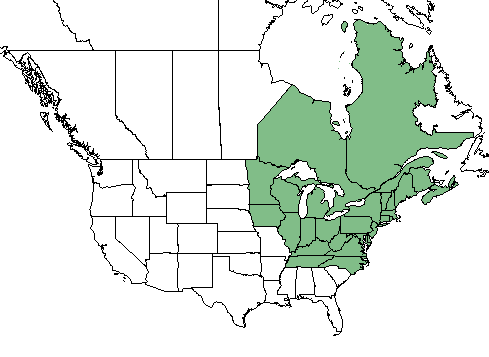

Skunk Cabbage tolerates northern weather.

“A more available food is found in the “cabbage” or young tuft of leaves, which in spite of inevitable prejudice on account of the odor of the bruised plant, makes not wholly unpalatable vegetable. During boiling no trace of the characteristic, disagreeable ordor is given off, but the cabbage should be cooked in several waters to which has been added a pinch of baking soda. Serve with vinegar and butter or other sauce. Our Italian immigrants often make use of these greens which, if prejudice were forgotten, might abundantly serve as large population. Our experience indicates that the plants vary, sometimes being quite mild, sometimes peppery. If one is in luck he will cook only the former.”

Fernald goes on to warn to not mistakenly collect the White Hellebore or Indian Poke (Veratrum viride) which grows in the same environment and is a “violent poison.” As for the skunky Trilliums the cooked leaves are edible but the roots are highly emetic and the berries questionable. Also know that nutritional information on the Internet supposedly for “skunk cabbage” is actually that of a totally different plant “swamp cabbage.”

Symplocarpus foetidus was coined by controversial British botanist Richard Anthony Salisbury nee Markham (1761-1829) and is from the Greek σνμπλοκη symplokee for “connection” and καρπος carpos for “fruit” referring to the ovaries connecting into a compound fruit. Foetidus is from Dead Latin meaning foul smelling.

Green Deane’s “Itemized” Plant Profile

IDENTIFICATION: Low growing, foul smelling to three feet tall growing. Roots are fleshy, tuberous, two inches long and an inch through, dark brown on the outside, white or yellowish inside.

TIME OF YEAR: Early spring, February in the southern end, end of spring northern end.

ENVIRONMENT: Swamps, wet woods, by streams, and or other wet, low areas, gullies.

METHOD OF PREPARATION: Dried leaves later boiled in changes of water, roots long-term dried edible. None edible raw. The roots are between one and three feet down, older ones have ring-like wrinkles.

Distribution of skunk cabbage in North America