Article and photographs by Green Deane

Brazilian Pepper is a personal unknown: You might like it but it might not like you. This is because many people are allergic to it on par with poison ivy. Others have used Brazilian Pepper for decades as a spice without incident.

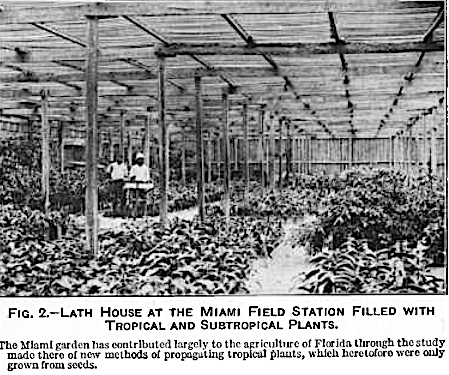

Native to Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay, this invasive species was imported to the United States in the 1800’s though when is a debate. Governmental records definitely say it was here just before the the 1900’s but the plant was listed in at least one seed catalogue as early as 1832. The U.S. Department of Agriculture got packages of seeds in 1898, 1899, and 1901 (one of them from Algeria.) Those seeds, or subsequent seedlings, were forwarded to the Plant Introduction Station in Miami where the species was studied. But it was Dr. George Stone of Punta Gorda, Florida, who championed the species in the 1920s changing the tree from a personal passion to a public menace. An amateur botanist Stone raised and gave away hundreds of plants. They were called “Florida Holly” and planted along the streets in Punta Gorda and elsewhere. In 1937 one company advertised the Brazilian Pepper as “one of our most worthwhile plants for general landscape purposes, as it makes a fine subject for mass planting and succeeds well along the beach, standing quite a lot of salt spray.” An article in the 1944 edition of the magazine “My Garden in Florida” said of the Brazilian Pepper “it ought to be in every garden in Florida.” Just six years later folks began to noticed it was becoming a serious problem. Brazilian Pepper is so invasive that today it’s in 20 counties of the state limited only by cold weather. Nearly everywhere it’s been imported it’s on the noxious weed hit list. Besides Florida and Texas it’s a serious weed in South Africa, Spain, Portugal, Australia, New Zealand, and on Pacific, Caribbean and Indian Ocean islands. In its native range it is not invasive.

The species itself is in the Anacardiaceae (Cashew) family which also includes poison ivy, poison sumac, poison wood, and mangoes, all known allergens along with cashews and pistachios. Toxicity in that family is usually caused by a resin. People can get contact dermatitis from Brazilian Pepper, welts from it like poison ivy, or rashes as from mangoes. Some people can get sick just being in the same room with the crushed berries. It has sickened researchers working with the fruit. The sap can cause lesions resembling second-degree burns. Brazilian Pepper can cause edema, and eye and facial swelling. When pollenating — usually September to October — it can be a severe allergen even though the pollen is sticky and heavy. Brazilian Pepper can intoxicate birds, injure livestock and can cause fatal colic in horses… Are you sure you want to try it as a spice?

I’m not allergic to the berries but I don’t care for the flavor. I have met six people, however, who use it; two couples and two individuals. In fact both couples have been using it as a spice for decades and one couple likes it so much they put it on pop corn. I know a man who, again for decades, uses Brazilian Pepper as a spice but only on fish and no other time. He grinds up a few berries in a mortar and pesetle as needed. I know a young man who eats the ripe berries off the tree. He doesn’t eat a huge amount of them at a time but he does eat them and I’ve seen him do it. I also know of a young woman who liked the flavor of the berries so much she used them extensively as a spice for a week — even on ice cream — and then got very sick from them. She couldn’t use them after that. So it’s across the board varying from individual to individual from some who consume it as a spice with no problems to others with a wide variety of sickening symptoms.

Pepper.

Despite its dubious nature Brazilian Pepper has several uses other than a spice. Bee keepers champion the species. Opinions on its honey vary: Some call it “esteemed” other say it is below “table grade.” It’s popular enough however to sell between six to eight million pounds annually. The taste is sweet with a mix of spicy aftertaste flavors. Honey becomes “Brazilian Pepper honey” when about 70% of the blossom visited by the bees are that species. The tree has also been used to make toothpicks, stakes, posts, railway ties and research shows it might make a good pulp wood. A resinous extract is used to protect fishing line and nets. It has been used to tan leather. The species also has many herbal applications. A 2017 study said in Brazilian herbal medicine it was used for: “…its antiseptic and anti-inflammatory qualities in the treatment of wounds and ulcers as well as for urinary and respiratory infections.” The study reported it might have some use against MRSA. It seems to interrupt the bacteria’s signaling capacity keeping it from releasing toxins thus giving the person’s immune system time to mount a counterattack.

As for the botanical name it is — as is so often the case — Greek mangled through Latin tongue-tied into English. The Latin Schinus comes from the Greek word Σχίνος (SKI-nos) which means “lentisk” which is the Mastic Tree. The genus name was chosen because Brazilian Pepper has similar foliage as the Mastic Tree which also exudes a sap. The English the genus is said SHY-ness or SKY-ness. Take your pick. The latter is closer to the original Greek. Terebinthifolius is also Greek but slightly less distorted: τερέβινθος (ter-REH-been-thos.) In English terebinthifolius is said terra-been-tha-FOE-lee-us which means “turpentine leaves.” The species’ name from the Terebinth Tree, Pistacia terebinthus, which is the turpentine tree in the Mediterranean area. With Brazilian Pepper you don’t have to crush them to smell them. Just bring them into a room. And for night time fun if you lignite the dry leaves their oil content is so high they can pop and sparkle.

Note it is illegal in Florida and Texas to sell, transport or plant Brazilian Pepper in any form. A relative, S. molle, is also found in Florida and Texas. Both are also in Hawaii, southern California and Puerto Rico. Brazilian Pepper seeds are popular with mocking birds, cedar wax wings, migrating robins and the Red Wiskered Bulbul. Raccoons and possums eat the seeds. Planted seeds have a high germination rate and sprout within three weeks.

Green Deane’s “Itemized” Plant Profile

IDENTIFICATION: It is an evergreen tree to 40 feet, low-branching, bushy, and spreading to equal width; the foliage is dense. Glossy leaves are aromatic with a red midrib, they’re about three inches long, compound, five to nine leaflets to a leaf. Flowers are tiny, white, compact, male and female blossoms on separate trees. Fruit is the size of a BB, 3/16 of an inch round, red, juicy, with an aromatic oil and a peppery flavor. The seed is yellow and kidney shaped. Sometimes it is mistakingly called “pink pepper corns” which is actually the fruit of a different species mentioned earlier, Schinus molle.

If you want to get technical there are actually four recognized varieties of Brazilian Pepper: var. acutifolius (lance-shaped leaves, tips pointed,) var. pohlianus (stems winged, stems and leaves velvety-hairy) var. raddianus (leaf edges toothed to toothless, tips rounded) and var. rhoifolius oval to obovate leaves, tips rounded.) They can be difficult to tell apart.

TIME OF YEAR: September to October or November is the main flowering season, fruits mature in December. However the tree can flower and fruit anytime of year and the fruit is persistent.

ENVIRONMENT: Dry or wet conditions. You’ll find it in waste ground, at waterfront, in right-of-ways, lawns, pastures, groves, dry lakes or even invading stands of larger trees.

METHOD OF PREPARATION: The ripe berries are dried then ground to a desired state and used as a spice. Some people eat a few ripe berries at a time.