Pawpaws (or papaws per Random House) can be among the most difficult and easy wild fruits to find. Finding the blossoms are easy. We saw some in Melbourne this past weekend. Finding the fruit, however, is more challenging. They like to hide and woodland creatures like to eat them making it difficult for us. The easiest way to locate pawpaws is find them when they’re blossoming and they are blossoming locally now.

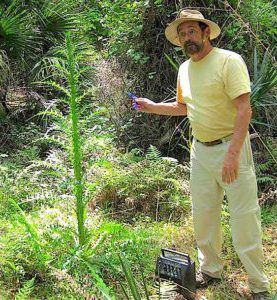

The most common place to spy pawpaws is and around pastures. Grazing livestock don’t eat the plants, blossoms or fruit. Look for bushy shrubs around five feet tall with magnolia-like cream-colored blossoms, or much smaller foot-size shrubs with dark ruby blossoms.

I can remember the first time I found a pawpaw. It was along a walking trail in Longwood, FL. At first I thought I had found a lumpy green pear but it was an unripe pawpaw. Interestingly pawpaws change greatly from hot Florida to the Smoky Mountain area. There, pawpaws are small trees.

There are two caveats: A chemical in pawpaws is still used to control head lice. And some people have a severe allergic reaction when eating them which is the prime reason they have not become a commercial fruit. That is, it’s not a significant health threat to the population at large but it is enough to give the lawyers fits. To read more about pawpaws, or papaws, click here.

I am often asked: Can you eat grass. The simple question has a complex answer: Yes, no, maybe.

Strictly speaking we eat a lot of grass, but in the form of grain: Wheat, rice, rye, barley, millet et cetera. What most folks want to know is can you eat the culms and blades (stems and leaves.) What you just saw is also one of the impediments to learning about grasses, an argot all their own, a specific vocabulary more complex than even mushrooms and often identifying characteristics can only be seen with a dissecting microscope.

Humans are not multi-gastric (or in theory large-gutted). We aren’t designed to break down the cellulose in grass. Cows have a four-chambered stomach for that purpose, horses have a huge large intestine, even the gorilla has a gut that can accommodate large amounts of vegetation. We don’t. However, what we can do is dry the grass, grind it into a powder and use it as a bulking agent in food, such as breads, soups and stews. We don’t get much nutrition from grass prepared that way but it does add to the sensation of satiety and reduces hunger. Then there is the issue of cyanide.

I have read and been told by two professors that all North American grasses are non-toxic. At the most basic level the means one has to know if the grass is native, which also requires identification, and I’ve already mentioned that group of plants can be a pain in the grass to identify. “Natives” would also include a lot species in the Andropogon family which I have never heard of having any use except perhaps making brooms. And some grasses have cyanide in them. Johnson Grass, a sorghum, is a good example. The large blades are full of it. Crowfoot Grass is another. We eat the grain of the latter but only after the plant has turned brown and the seeds are easily picked. Quite a few toxic grasses from Africa and Asia are naturalized in North America.

Personally I stick to a few grains, Sand Spurs, Barnyard Grass, and some Panicums. But then there is Timothy.

Permit me to reminisce on this rainy March day a week after both my parents’ birthdays: One of the books in my foraging library is A Guide to Florida Grasses, by Walter Kingsley Taylor, not the first book in my collection from this august author. I spent an afternoon recently browsing through the guide and noted his entry on Timothy Grass. The picture alone erased more than 50 years and took me back to summers as a boy when I was impressed into service to harvest hay for our five horses, most of it Timothy, Phleum pratense, a grass originally from Europe. We “hayed” nearly every summer for some 20 years, usually putting into the barn ten to 15 tons of loose hay. (There is some irony in that most of the hay we got every year came from the Hayward Farm.)

The main machine for cutting this hay was a horse-drawn sickle mower though in later years we moved up to a tricycle tractor. Instead of two horses the mower’s tongue was extended four feet and was pulled by a stripped-down WWII Jeep, which I got to drive. As soon as I was old enough to reach the pedals I drove and Dad operated the mower. By the time I was legally old enough to get a driver license I had already driven thousands of miles in hayfields and across country roads in a four-wheel drive stick shift. Most of my annual summer “vacation” was spent haying and driving. It wasn’t time off.

The problems of haying became common. The cutter bar would break a tooth which is a triangle-shaped replaceable cutting edge held on by rivets, which we replaced red hot from our own forge. At least once a season, more depending upon how thick the grass was, the piston arm would break, as it was intended to do. It’s a piece of ash called a pitman that pushed the mower blade back and fourth being moved by gears turned by the wheels of the mower (turning forward motion into side motion.) When stresses got too much the wooden piston would break saving the rest of the machine from damage. Two other problems were common:

Often the cut hay would wrap around each of the Jeep’s drive shafts, build up like a wad of cotton candy, get hot and catch on fire, not far from the gas tank. This required quick stopping, crawling under the hot vehicle, putting out the fire, then removing the tightly wound hay, often, ironically, with a blow torch. The other issue, beside unpredicted rain, was ground hornets. The Jeep, pulling the mower, would run over a ground hornets’ nest — at least one per field. They were never pleased about that. The hornets would instantly swarm under the Jeep, then emerge between the back of the jeep and the mower where they would find both of us and attack. It was an excuse to change gears and drive like hell…

In places where the terrain was too wet or hilly my step-father, who was built like a heavy-weight boxer and did box, would take out a scythe and cut it by hand. He had two grim reaper scythes. One with a long thin blade for hay and one with a short thick blade for brush. Once the hay was cut and sun dried we would winnow it with a Jeep-adapted horse-drawn rake. Then it was loaded loose onto a hay wagon I would drive home. As the hay was lifted into the barn — a hay fork pulled by the Jeep which my mother drove — my job on those oh-so-hot summer nights was to go up in the high rafters of the barn with 100 pounds of salt for each ton of hay. As each forkful of hay was dumped into the barn I salted it to absorb any moisture thus preventing it from rotting, getting hot and starting a fire in the barn. And then… then throughout the winter I had to shovel and cart the recycled hay to the manure pile. No wonder I was a skinny kid. I don’t know which I shoved more of growing up: Manure or snow.

And all the time — driving or shoveling — I had a stem of Timothy Grass in my mouth, chewing away enjoying the mild sweetness. It is a grass I would dry, powder, and use. Being a farm kid and chomping on Timothy was part of the same existence. It’s one grass that I know beyond any doubt. Timothy was unintentionally introduced to North America in 1711 by one John Herd. He called it “herd grass.” Clever. He talked it up and it was grown in southern Canada, the New England area and New York. In 1720 a Timothy Hanson moved from New England to Baltimore and began to cultivate the seed and sell it. He was the first person in the new world who grew, bagged and sold hay seed. George Washington and Benjamin Franklin were admirers of the grass and Franklin is credited with calling it “Timothy Seed.” The name was shortened to Timothy and it stuck. It’s found nearly everywhere in North America and even in Greenland. I chew it when I hike the Appalachian Trail. I sometimes wonder what my youth would have been like — and adulthood — had Messers Herd, Hanson and Franklin not known good grass when they saw … or chewed it.

Foraging Classes: As the weather warms up the classes get larger and fill up sooner. This week I have a class in Orlando and southwest Florida in Port Charlotte.

Saturday, March 23rd, Blanchard Park, 10501 Jay Blanchard Trail, Orlando, FL 32817. Meet near the tennis court near the YMCA building. 9 a.m. to noon.

Sunday, March 24th, Bayshore Live Oak Park, Bayshore Drive. Port Charlotte. 9 a.m. to noon. Meet at the parking lot at the intersection of Bayshore Road and Ganyard Street.

Sunday, March 31st, Dreher Park, 1200 Southern Blvd., West Palm Beach, 33405. 9 a.m to noon. Meet just north of the science center in the north section of the park.

Saturday, April 6th, Florida State College, south campus, 11901 Beach Blvd., Jacksonville, 32246. 9 a.m. to noon. We will meet at building “D” next to the administration parking lot.

Sunday, April 7th, Boulware Springs Park, 3420 SE 15th St., Gainesville, FL 32641. 9 a.m. to noon. Meet at the picnic tables next to the pump house.

Saturday, April 27th, Red Bug Slough Beneva Road, Sarasota, FL, 34233. 9 a.m. to noon.

All foraging classes are at least three-hours long, some closer to four depending on location, time of year and size of the class. To learn more about the foraging classes go here.

Don’t even consider trying to eat the blossom of the Salvia coccinea, the Scarlet Sage. While it blossoms year round it’s currently responding to the warm weather with wonderful displays of scarlet red blossoms. They look like they would be bright additions to a salad but my personal experience is they are not. The Scarlet Sage is the main reason why I’m opposed to “field testing.” Several years ago I thought the blossom might be a good salad addition. I researched the species extensively. It’s a native and has been exported around the world for 400 years. There were no reports of toxicity, only one medicinal report, and came from a good family, the sages. I decided to field test the plant under very controlled conditions. That’s means I had researched the plant well, knew exactly what I was doing, was NOT in an emergency situation, had good health insurance and a hospital nearby. Those are the only acceptable conditions, in my opinion, for “field testing.”

I began the field testing in stages. On the appropriate day of the schedule I ate a piece of the red blossom that was 1/8 of an inch square, which was as exact as I could get with my Exacto blade and the delicate blossom. I ate it. It was peppery. Forty minutes later my head spun into space and my stomach twisted into a cramp and I was ill for three weeks. I was close to going-to-the-emergency room ill within the hour. By day two I was just sick. Pepto Bismo calmed the stomach and Coca-cola syrup (both from the pharmacy) controlled the nausea. For those three weeks I consumed little food and downed too much Pepto Bismo and Coca-cola syrup. I was truly miserable.

Imagine if I were not intentionally testing the plant under optimum conditions? What if it had been an emergency, that I was responsible for others and I took it upon myself to “field test’ an unknown plant as, unfortunately, far too many “survival” books recommend. I would have been out of commission, useless, of no help to any one exactly when needed the most. You can function hungry, it’s much harder to function when you’re sick. And if you “field test” the wrong plant you could be more than just sick. The next time someone starts to teach you the “field testing” method ask them one question: What plant do you eat now that you discovered by field testing? The answer is always “none.” Then ask: “have you actually ever field tested a plant?” The answer is usually “no.” A lot of folks are teaching something they have never done. I turned down a lucrative fee to go to a convention and teach “field testing.” I don’t think “field testing” should be done in the field. Just the opposite: If ever field testing should be done under very controlled conditions after a lot of research and with medical facilities near by and not during an emergency. Tropical Sage and Pineapple Sage look much alike but the latter smells like pineapple, the former does not. (There’s another picture of the non-edible Salvia coccinnea here on my “don’t eat this” page.)

This is a good opportunity to talk about an edible blossoming now and discuss a little botany as well. Wisteria are blooming but only for a week or two. Outside of some mushrooms very few wild edibles have such a short seasonal run. Only the blossoms are truly edible and they are here for a very short time. This also makes them difficult to study. You almost have to harvest them when you see them. If you go back a few days later they are often gone for the year. Looks for vines now with large aprays of lilac-colored blossoms. As for the botany…

A Spike and a Raceme are similar inflorescences (blossom) but they have a distinct difference. First an inflorescence is a flowering system that has more than one blossom. A Dandelion is NOT an inflorescence. A Black Cherry blossom, which has many flowers, is an inflorescence. Both a Raceme and the Spike have multiple blossoms along a stem. However, the Raceme blossoms have short stems of their own (called petioles) that attach to the main stem. The Wisteria, above right, is a Raceme, many blossom on the main stem and each blossom having its own short stem. Blossoms on a “spike” attach to the main stem directly. They do not have short stems (petioles.) The common Gladiolus, below left, is a spike, and a rather large one. Those blossoms do not each have a stem of their own. The Gladiolus blossoms attach to the main stem directly

Note on both the Raceme and the Spike older flowers are larger than the newer flowers which are near the end, quite obvious on the Gladiolus. Usually ripening of the fruit or seed on both also proceeds from nearest the plant towards the end away from the plant. Both Gladiolus and Wisteria blossoms are edible. To read about Gladiolus click here, to read about Wisteria click here.

Want to identify a plant? Looking for a foraging reference? Do you have a UFO, an Unidentified Flowering Object you want identified? On the Green Deane Forum we chat about foraging all year. And it’s not just about warm-weather plants or just North American flora. Many nations around the world share common weeds so there’s a lot to talk about. There’s also more than weeds. The reference section has information for foraging around the world. There are also articles on food preservation, and forgotten skills from making bows to fermenting food. One special section is “From the Frightening Mail Bag” where we learn from people who eat first then ask questions later. You can join the forum by clicking on “forum” in the menu.

All My Videos are available for free on You Tube. They do have ads on them so every time you watch a Green Deane video I get a quarter of one cent. Four views, one cent. Not exactly a large money-maker but it helps pays for this newsletter. If you want to see the videos without ads and some in slightly better quality you can order the DVD set. It is nine DVDs with 15 videos on each for a total of 135 videos. Many people want their own copy of the videos or they have a slow service and its easier to order then to watch them on-line. The DVDs make a good gift for that forager you know especially as spring is … springing. Individual DVDs can also be ordered or you can pick and choose. You can order them by clicking on the button on the top right hand side of this page (if your window is open wide enough.) Or you can go here.

Donations to upgrade EatTheWeeds.com have gone well. Thank you to all who have contributed to either via the Go Fund Me link, the PayPal donation link or by writing to Green Deane POB 941793 Maitland FL, 32794.

This is weekly issue 347.

Oh, it is too bad you did not have or know to take Activated Charcoal as it could have adsorbed the plant material and kept you from being so sick. But thanks for the reminisces, the warnings, the history and about plants. I did not realize many people are allergic to paw paws. Personally, I do not care for them.

Thanks for the very useful info. particularly that dealing with bulky food of grass and cyanide poisoning. Please send me the newsletter via my present email.

Good newsletter! I love how I see in real time in the field what you are writing about Deane, it really helps with the ID!

I know Paw Paw as a tree with fruit similar to mango. Very fragile fruit but delicious!