Plants can’t run. That’s why the vast majority of them are unpalatable or lethal. Guesstimates range from 5 to 10 percent of plants are edible. Let’s split the difference at 7.5%, with a higher percentage towards the poles and lesser percentage towards the equator (percentage of overall edibles, not sheer numbers. Most plants in the tundra are edible, most plants at the equator are not. )

Through trial and error both animals and people have learned which ones are dinner and which ones are death. In fact, many of our “edible” plants are toxic at some time or in some way. The seeds of most plants in the Prunus clan (apples, cherries, peaches, plums) et cetera are toxic, though many peoples have discovered ways to eat them, which suggest to me a lot of hunger. You don’t figure out how to eat something with cyanide in it unless you’re hungry.

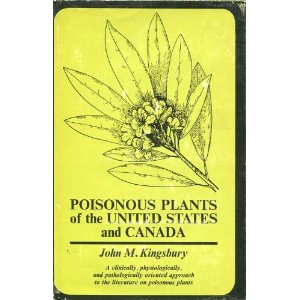

It is wildly reported that a man saved up a cup of apple seeds, ate them and died. It was reported in Poisonous Plants of the United States and Canada, by John M. Kingsbury, 1964. But he got that from a farm bulletin in 1942 which said it happened but did not say who, when or where (see my article on wild apples.) My mother always eats the entire apple, seeds and all, but it’s a few seeds at a time. And my grandmother ate the pit of every northern fruit seed she ever ate, but only one at a time. Many grains have toxins and a lot of legumes in the pea family are only edible when young. Tapioca, cassava, and cashews start out non-edible. Even potatoes can be toxic.

It is wildly reported that a man saved up a cup of apple seeds, ate them and died. It was reported in Poisonous Plants of the United States and Canada, by John M. Kingsbury, 1964. But he got that from a farm bulletin in 1942 which said it happened but did not say who, when or where (see my article on wild apples.) My mother always eats the entire apple, seeds and all, but it’s a few seeds at a time. And my grandmother ate the pit of every northern fruit seed she ever ate, but only one at a time. Many grains have toxins and a lot of legumes in the pea family are only edible when young. Tapioca, cassava, and cashews start out non-edible. Even potatoes can be toxic.

Deadly Death Cap Mushroom

No one wants to eat a toxic plant. But how often does it happen? In today’s society serious poisoning by accidental ingestion of plants is extremely rare in both adults and children. However, many plants can make you ill. Mushrooms, of course, get a lot of headlines. But that’s something of a distortion with the large majority of them being Asian immigrants collecting a toxic look-alike to a mushroom back home. Still, there is an occasional amateur mycologist or mushroom expert who gets it fatally wrong. Statistically oleander kills more adults than any other plant, but that’s because it is the suicide plant of choice in Sri Lanka, tallying several thousand a year. It was unheard of 30 years ago but two girls had a suicide pact and used oleander seeds. The resulting publicity spread the practice.

In the United States children are the most common victims of plant poisonings. Three quarters of those happen in their own yard. If you add your neighbor’s yard that covers most of the accident plant poisonings. This is specially true of toddlers (and young pets) who will chew anything regardless of taste. It is also a liability of slightly older children who see mom and dad foraging and just assume they can to, which brings up two issues.

First, if you are going to forage and you have children they have to be told the limits. They can’t just pick plants on their own. The other is in the past man’s knowledge of plants was vast because they were extremely important to day to day life. People knew the plants around them and children grew up knowing which plants were edible and which ones were not. Now most don’t know, and worse, when we moved to suburbia we surrounded our homes with ornamental plants, most of which are very toxic. That adds up to an increase in poisonings. And in one case out of nine with kids, the offending plant is never identified.

Toxic Air Potato

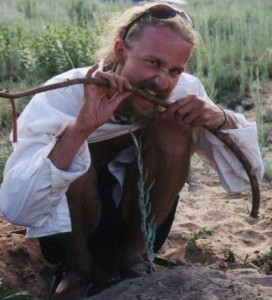

What about poisonings among foragers? I do not know anyone who was seriously ill from eating toxic plants though I know of two, both of whom tried eating the bulbils of the Dioscorea bulbifera which in some varieties are edible and in others toxic. Preparation is also an element. In fact, the last time I was writing about those bulbils and saying don’t eat them I had a visitor from Brazil. He told me his mother cooks them all the time. This is one of the problems with that genus, and a few others. I have research on my desk right now about a nightshade that the state of Florida says is toxic and the state of Louisiana says is edible. That the plant has seven very close toxic look alikes does not help. This is when my faith in state botanists isn’t rock solid.

Deadly in minutes

Frankly, I think there will be more poisoning of foragers. I get a lot of email about foraging, much of it from people who prefer to watch videos about plants rather than study them and get it right. One is particularly chillling. Every plant one fellow has asked me about eating has been poisonous. Every one. No exceptions. He’s been 100 percent wrong so far. It is difficult to imaging anyone being that wrong so much. If he’s planning on eating wild foods he is certainly won’t be doing it for long. Another wrote to tell me saying if a plant tastes good he eats it, if not he doesn’t. He asked me what I thought of that. I said I hoped he had good life insurance and a will made out. Several lethal plants taste good, the yew seed perhaps the best tasting of all. It will stop your heart. Poison hemlock root is reported to be very delicious. It can also kill you in 15 minutes.

As far as lethality goes, there are three local plants — not counting mushrooms — that will not only kill you but do so quickly, painfully and with no antidote. There is one report that one of them is edible if prepared correctly. Unless starving I ain’t volunteering, and maybe not then.

As for expert and medical opinion… Some states list wild strawberries as toxic. I have no idea why. But I certainly have eaten more than my fair share. Acorns make the list, too, though they sustained native populations for thousands of years and Japan during WWII. The tannins in them are hard on your kidneys if you can manage to eat the bitter ones.

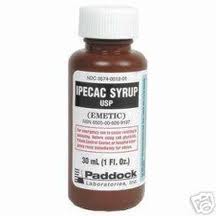

It is also now recommended that one not administer syrup of ipecac if you or someone has eaten something toxic. Ipecac will make you throw up inside of 20 minutes. The rationale behind this is shaky and I carry ipecac in all my backpacks and vehicles. Not for me per se but for accidental others I might meet. The view of not administering ipecac rests on the assumption the victim can be gotten to a hospital quickly (the same view is held about treating snake bites. The “medical advice” is get them to the hospital. Not helpful in the field.) The attitude is, ‘don’t you amateurs do anything. We doctors will take care of it.’ Personally, I like to be prepared as if I am several days from medical help. In that case, ipecac can be a life saver, just like knowing how to treat a snake bite.

It is also now recommended that one not administer syrup of ipecac if you or someone has eaten something toxic. Ipecac will make you throw up inside of 20 minutes. The rationale behind this is shaky and I carry ipecac in all my backpacks and vehicles. Not for me per se but for accidental others I might meet. The view of not administering ipecac rests on the assumption the victim can be gotten to a hospital quickly (the same view is held about treating snake bites. The “medical advice” is get them to the hospital. Not helpful in the field.) The attitude is, ‘don’t you amateurs do anything. We doctors will take care of it.’ Personally, I like to be prepared as if I am several days from medical help. In that case, ipecac can be a life saver, just like knowing how to treat a snake bite.

The coloring screams toxic. Listen to that.

Are there some plant warning signs we should keep in mind as foragers? Absolutely. Like some creatures, colorful plants or parts can be a warning to stay away. Modern landscape plants are almost always toxic. Avoid all plants with white berries as 99.999999 of them are toxic and the rest don’t taste good. Avoid plants with white sap, 98% of them are toxic, with some notable exceptions: Learn them. I can think of four prime ones. Bitter tasting plants are often toxic. Purple or red shoots should be avoided. View every mature legume or pea as toxic. There is no taste test for edibility. And the so called field edibility test is more dangerous than helpful.

I am not a mushroom hunter but this I can tell you: Never eat little brown mushrooms. Burn that into your memory: NEVER EAT LITTLE BROWN MUSHROOMS. Yes, I know they are cute and fresh and everywhere and tempting. Just don’t do it. No exceptions. Even experts can’t tell them apart. White mushrooms with gills are more toxic than not. Avoid them. Mushrooms without gills and mushrooms on trees may make you very sick but probably won’t kill you. That is not too comforting when you are in the hospital. If you are going to eat any mushroom, study with an old expert, a very old expert.