Malus sieversii, Hard-Core Apples

Wild Apples are one of the most common over-looked foraging foods. People take one taste, spit it out, and go on their way.

Because of the story of Johnny Appleseed (who was a real person) most folks think apples aren’t native to North America. There were plenty of apples here when Europeans arrived but they were Wild Apples not cultivated apples. What’s the difference? Taste and size. Most wild apples are small and sour, domesticated apples tend to be larger and sweeter. What most people don’t know is that wild apples can be baked or roasted (as in near an open fire or in an oven) and made very tasty. While some wild apples are too bitter to eat even after cooking many are transformed into good eats.

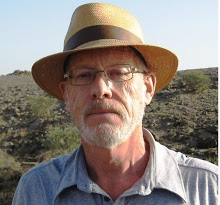

When I was a kid foraging in the Maine woods wild apples were very common. In fact, of the eight or so feral apple trees I knew of only one had a cultivated heritage. It was a Golden Delicious, and my least favorite. The rest were usually sour raw but wonderful when roasted by a campfire (and no pots to clean.) Unfortunately there are few if any Wild Apples in this area of Florida. It is simply too hot. They like northern climes and northern people liked wild apples, too. No less a person than New England native Henry David Thoreau wrote a 10,000-word essay on the Wild Apple.

The domestic apple as we know it has been around some 6,000 years and came from Kazakhstan. There apple trees growing to 60 feet were the dominant species of the forest. That is something to think about, apple trees the size of Oaks, a forest of them… Orchards there today are remarkable in that the trees are very resistant to disease, unlike commercial crops. Further, two apples from that area — the Red Delicious and the Golden Delicious — are the parents of 90% of modern commercial eating apples. The Red Delicious was hybridized into the Fuji and the Empire, and the Golden Delicious into the Gala, the Jonagold, the Mutsu, the Pink Lady and the Elstar. The Granny Smith (below right) however, came from a back yard in Australia.

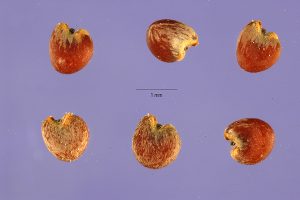

It originated in 1868 from a chance seedling propagated by Maria Ann Smith (née Sherwood) born 1799, died 9 March 1870. Researchers think the now well-known green apple was a chance cross between Malus sylvestris, a European Wild Apple — perhaps from France via Tasmania — with the domestic apple M. domestica. Widely propagated in New Zealand. It was introduced to the United Kingdom around 1935 and the United States in 1972. Each Granny Smith apple today is a clone. Actually every commercial apple is a clone. One cultivated apple that does grows in Florida is the Apple Anna, which was a chance seedling found in the Bahamas and can withstand the summer heat. Worldwide some 55 million tons of apples are harvested annually worth some $50 billion annually. Americans eat on average, as of this writing, 126 apples a year each. Meanwhile wild apples, which are free, feed mostly wildlife.

Often a wild apple’s taste will be moderated because of hybridizing with cultivated apples. There are no hard and fast rules identifying which are edible raw. You just have to taste and experiment with each wild apple tree you find. They also usually have more cholesterol-reducing pectin than cultivated apples thus are added to other fruits and domestic apples when making jelly. Incidentally, there is no such species as a “crabapple” per se. Crabapple, like “pearl onion” is a reference to size. Crabapples, like pearl onions, are small and any small apple can be called a crabapple as any small onion can be a pearl onion. The fascinating aspect of apples is that every apple seed is totally different than the parent tree. Something like snow flakes no two apple seeds are genetically alike thus what kind of tree each will produce is a mystery. Every named apple you eat came originally from just one seed and one tree. As mentioned above they are clones which is why it takes a long time to get a new apple into production.

Besides foraging for wild apples I used to help my father make pieces of apple wood into tobacco pipes. We’d find a suitable size piece, rough cut and drill it then boil it for a few hours to drive the sap out of it. Then it was carved and sanded. A bit of bass wood became the stem. I still have one of them around after more than 50 years. You can read about that here. If you are a hunter wild apples trees are a good place to find game. When I roamed the woods as a boy wild apple trees were the prime place to flush partridge in the fall and later deer. A huge variety of wildlife like the apple among them foxes, raccoons, bears, coyotes, opossums, rabbits, squirrels, grouse, prairie chickens, and quail. They know good food when they find it.

Malus sieversii (MAL-us see-VER-see-eye) is the botanical title for these wild fruits. Malus is the Dead Latin word for apple, and Sieverrii honors Ivan Sievers, a Russian botanist who discovered the wild apples in 1793 in Kazakhstan but died before describing the species. The name was given by Carl Friedrich von Ledebour, who got there in 1830. The word “apple” is also from Dead Latin and means fruit. All that said what about Johnny Appleseed (John Chapman, September 26, 1774 – March 11, 1845.) While he wore a tin pot for a hat and a burlap sack for a shirt, and went barefoot even in the winter, he was an astute businessman. He bought or got land grants ahead of settlers and started apple tree nurseries so when the settlers arrived he had trees to sell. Then he would leave his nurseries in the hands of a local and set out for the frontier again.

While I am on the topic, what about eating apple seeds? There are two things we know for certain: Eating a few at a time is fine, eating a huge amount can make you ill and possibly kill you. What’s a few? What ever seeds you find in one apple is no big deal. In fact, my mother — who died at 88 — often ate a quarter of a cup of seeds at a time but that was living dangerously. For the average person of average weight the fatal dose would be around 114 average-size seeds thoroughly chewed. And what about the story that a man saved up a cup of seeds, ate them, and died from that?

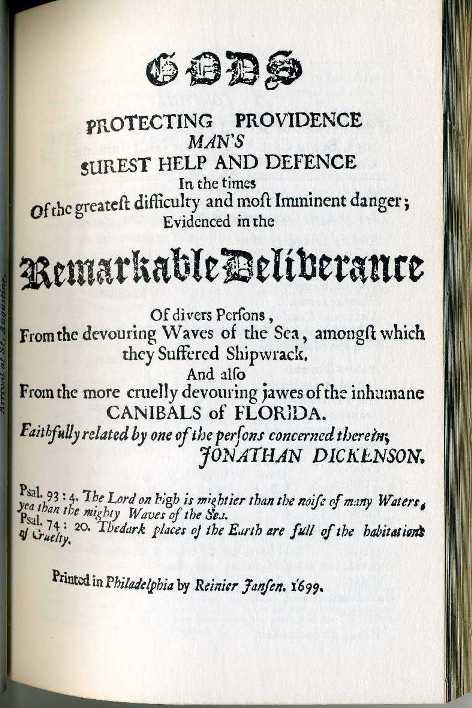

The story got legs when a prominent expert on toxicology, Dr. John M. Kingsbury included it in his book Poisonous Plants of the United States and Canada, Prentice-Hall, 1964. Kingsbury was an associate professor of botany at New York State College of Agriculture and lectured on poisonous plants for the veterinary college. Everyone presumed Kingsbury had proof. But in 1998 in the Journal of Clinical Toxicology there was a letter to the editor grousing about folklore and “plantlore” specifically mentioning Kingsbury. That got me interested in the veracity of the death-by-appleseed story. To be specific I wanted to know the name of the man who ate a cup of apple seeds, where, and when did he die? Basic facts. After all, Kingsbury’s inclusion in his book gave the story legitimacy and it has been quoted extensively ever since. Kingsbury’s bibliography quoted two authors more than two decades earlier: Reynard, G.B., and J.B.S. Norton in Poisonous Plants of Maryland in Relationship to Livestock. Maryland Agricultural Experimental Station, Technical Bulletin. A10, 1942. 312pp. That would make sense as they and Kingsbury had an interest in plants that were toxic to farm animals.

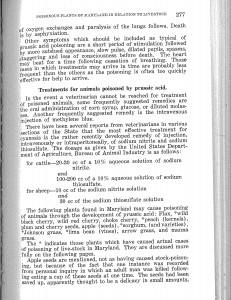

On page 276 of the bulletin Reynard and Norton write about prussic acid harming livestock. (Amygdalin is essentially a sugar and cyanide molecule which is safe until digested where upon it releases hydrogen cyanide which used to be called prussic acid.) The cyanide blocks the uptake of oxygen by red blood cells causing asphyxiation. How much material, how chewed the material is, the liquid dilution of the material in the stomach, and how many stomachs you have and your size all affect the extent of the poisoning. In the listing of plants that can harm animals via prussic acid Reynard and Norton include flax, wild black cherry, wild red cherry, choke cherries, peach (kernels) plums, cherry (seeds) apple (seeds) sorghum, lima beans, arrow grass and manna grass.

They note in the last paragraph (photo left:) “Apple seeds are mentioned, not as having caused stock-poisoning, but because of the fact that one instance was recorded from personal inquiry in which an adult man was killed following eating a cup of these seeds at one time. The seeds had been saved up, apparently thought to be a delicacy in small amounts and upon being eaten developed enough of the deadly prussic acid to cause this tragic death. The instance is recorded here as a caution to others who might attempt to eat more than a few of these seeds at any one time. Previous investigators have reported that apple seeds contain appreciable amounts of amygdalin from which prussic acid is developed, but actual reports of poisoning are rare. “

So rare they didn’t or couldn’t say who actually did die from eating apple seeds if anyone ever did. Their reference — a personal inquiry — is as weak as Kingsbury’s. Without a name, a time and place it is but an early urban legend. It may be that someone indeed did died from eating a cup of apple seeds. It is theoretically possible. I say theoretically because if it did happen it was before 1942 and no one thus far in any professional paper has ever identified who it was if anyone. The best one can come up with is a no-referenced warning in a livestock bulletin 72 years ago. A 130-year search by this writer of the New York Times of 437 stories involving prussic acid revealed suicides, murders and a few accidental medicinal deaths. None by an appleseed overdose. I think that would have made the newspaper. The point is the seeds in one apple a day won’t kill an adult. To be on the safe side however, kids, because they are so much smaller, should not eat apple seeds.

For some of the above material I want to give special thanks to Stephanie M. Ritchie, Alternative Farming Systems Information Center, National Agricultural Library, 10301 Baltimore Avenue, Room 132, Beltsville, MD 20705

Green Deane’s “Itemized” Plant Profile

IDENTIFICATION: A tree seldom more than 20 feet high with a contorted and rigid crown, branches often short and spur like, thorn-like twigs, leaves alternating saw-toothed, obvious network of veins on either side of the leaf. Quintet of pinkish or white petals, scented. If you cut the apple through at the equator you should see a star shaped core where the seeds develop.

TIME OF YEAR: Fall, if not late fall

ENVIRONMENT: Likes all terrain that is not bone dry or sopping wet, often found on the south side of hills.

METHOD OF PREPARATION: Jelly, fruit, drink, source of pectin. Often they are improved greatly by roasting near a fire or in an oven.