World’s Largest Acorn

Acorn: More than a survival food

The first time you eat an acorn it makes you wonder what the squirrels are going nuts about. As the bitterness twists your mouth into a pucker it reminds you that animals can eat a lot of things we can’t… unless we modify them.

A lot has been said about acorns in foraging publications. I’ll try to say a few things that haven’t been said. Let’s start with that fact that the world’s biggest acorn is in Moore Square Park in downtown Raleigh, North Carolina. Raleigh calls itself “The City of Oaks.” The “Big Acorn” is 10 feet tall and weights 1,250 pounds. I’d hate to meet the squirrel that can carry it away. But, it does remind me of a general rule of thumb about acorns: The bigger the cap on the acorn, compared to the size of the nut, the more bitter the nut will be.

The English word “oak” is some 1,260 years old. In German it was “eih” ending up “eiche.” The Dutch extended it to “eychen” or ” eychenboom.” (I went to school with a “Cossaboom” meaning cherry tree.) Oaks are also mentioned in ancient texts. Greeks of old said “dryas.” Modern Greek say “dris.” It was the preferred tree of Zeus (whom the Greeks call ZEFF, rhymes with Jeff. Zeus is mangled through Dead Latin then into English.) Those faithful to ZEFF… ah… Zeus… gathered around oak trees. The Celts preferred to knock on oak wood. One variation of their word for oak was “dair, the fourth letter of the Celtic alphabet and part of the name of the city Kildare (which means “Church in the Oaks.”) Often associated with strength, the US military awards gold “oak leaf clusters” for exceptional bravery. Oaks have been a significant part of every culture around them.

The English word “oak” is some 1,260 years old. In German it was “eih” ending up “eiche.” The Dutch extended it to “eychen” or ” eychenboom.” (I went to school with a “Cossaboom” meaning cherry tree.) Oaks are also mentioned in ancient texts. Greeks of old said “dryas.” Modern Greek say “dris.” It was the preferred tree of Zeus (whom the Greeks call ZEFF, rhymes with Jeff. Zeus is mangled through Dead Latin then into English.) Those faithful to ZEFF… ah… Zeus… gathered around oak trees. The Celts preferred to knock on oak wood. One variation of their word for oak was “dair, the fourth letter of the Celtic alphabet and part of the name of the city Kildare (which means “Church in the Oaks.”) Often associated with strength, the US military awards gold “oak leaf clusters” for exceptional bravery. Oaks have been a significant part of every culture around them.

The larger the cap the more tannic acid

The word “acorn” is a combination of “ak” for oak and “corn” meaning seed thus acorn means “oak seed.” The Greeks say velanidi, the Spanish bellota, the French gland, Italians glanda, Portuguese, glande, and in the forgotten fifth romantic language, ghinda in Romanian. Those Romans got around. All the Romantics come from the Latin word for gland, which also lent itself to the medical term for a certain acorn-like part of the male anatomy. The acorn is also one of the few nuts or fruits that is not directly named in Modern English after the tree it comes from. This is why one does not hear of oak nuts… walnuts, beechnuts, hickory nuts, oak nuts… gland… it could all get rather naughty.

The smaller the cap, the less tannic acid

At least 450 species of oak populate world wide. Some 30 species in the United States have been used for food and oil. The Live Oak is the most prized, not only for food but particularly ship building. Its very long, graceful limbs were ready-made for boat keels and ribs. In fact, the U.S. Navy once had its own Live Oak forest just for boat building. Sold off long ago, the Navy began stockpiling Live Oak in 1992 for restoration of the USS Constitution. It got 50 live oaks from Florida in 2002 of 160 that were cleared for a golf course near Tallahassee. Just as 200 years ago, the trees were selected for their natural curves for the ship. In the white oak family, the Live Oak’s acorns are among the mildest one can collect. Botanically the Live Oak is Quercus virginiana. Quercus (KWERK-kus ) was the Roman name for the tree and virginiana (ver-jin-ee-AY-nuh) means North America and usually where the species was first noticed, such as Virginia. (If you want to get confusingly technical “Ilex” — the genus name for Hollies — also means “oak.” Early botanists thought the Hollies in North America were oaks so they called them Ilex, which was the name of an evergreen oak. When the mistake was found out Hollies kept the oak-genus name and the Oak genus was changed to Quercus.)

Storing acorns the Acorn Woodpecker way

The seed crop from an oak, the acorns, is called a “mast” which means “food” and putting on a crop of acorns is masting. It is tempting to say it is probably related to the word to “masticate” meaning to chew but it isn’t. Mast came from the Middle English word “mete” meaning meat, which at that time meant any food, and we still use it abstractly in that way, as in “Education became his meat and experience his drink.” Mete came from the Italian word madere which came from the Greek word, madaros, meaning to be wet. That takes a bit of explaining: Ancient Greeks divided food into two large categories. “Wet” food was food fit for humans and pigs. Dry food was fit for cattle and fowl. Now you know. How many acorns a tree produces is directly related to the amount of rain in the spring time of the year it is supposed to mast. The more rain the more acorns.

Acorns are quite nutritious. For example, the nutritional breakdown of acorns from the Q. alba, — the white oak — is 50.4% carbohydrates, 34.7% water, 4.7% fat, 4.4.% protein, 4.2% fiber, 1.6% ash. A pound of shelled acorns provide 1,265 calories, a 100 grams (3.5 ounces) has 500 calories and 30 grams of oil. During World War II Japanese school children collected over one million tons of acorns to help feed the nation as rice and flour supplies dwindled.

Live Oak leaves have no teeth

Oaks fall into two large categories, those that fruit in one season, white oaks, and those that fruit after two seasons, the black oaks and the red oaks. The latter category can be more bitter than the former. The first category have leaves with round lobes and no prickles at the end of the leaves. The black and red oaks have prickles at the end of their leaves. They also have scales on the caps of the acorns, hair inside the caps, and a sheath around the nut (which always throws a color even when the tannin is leached out.) Sometimes those in the first category don’t need any leaching, or very little. The rest always do. But first, separate the acorns.

Floaters are bad or have a usable grub in them

To separate acorns dump them into water and remove the ones that float. Take the ones that sink and dry them in a frying pan on the stove or in the oven at 150F or less for 15 minutes, preheated. Or put them in the sun for a few days. You don’t want to cook them yet, just dry them off and shrink the nut inside making them a little easier to shell. The yield, not counting bad acorns, is 2:1. two gallons of usable acorns in the shell will yield a gallon of nut meat. We must leach out the tannic acid it can damage our kidneys, Most unleached acorns are too bitter to eat without leaching.

Soaking in cold water, minimal energy and the starch is not cooked

There are three general ways to leach acorns. The least common way is to bury them whole in a river bank for a year, which turns them black and sweet, good for roasting. The other method is to grind them into a course meal and soak several days or weeks (depending on the species) in many changes of cold water until the water runs clear. These will be slightly bland but good for making acorn flour. (Sometimes the leached acorns will be dark but sweet afterwards.) The third way — boiling — is least preferred because if done wrong it will bind the tannins to the acorn and they will not lose their bitterness. Also, when you boil the acorns you also boil off the oil with the tannins, reducing their nutrition. That oil, however, is very nutritious. At this writing it is selling for about $10 an ounce. You can make it for far less. There is actually a fourth method of processing that requires lye but it is not commonly used nor have I tried it.

Boiling speeds up the process but cooks the starch

The boiling process requires two pots of boiling water. Put the acorns in one pot of already boiling water until the water darkens. Pour off the water and put the hot acorns in the other pot of boiling water while you reheat the first pot with fresh water to boiling. You keep putting the acorns in new boiling water until the water runs clear. Putting boiled acorns into cold water will bind the tannins to the acorn and they will stay bitter. So always move them from one boiling bath to another. Putting acorns in cold water and bringing the water to a boil will also bind the tannin. So it is either use all cold water and a long soaking or all boiling water and just a few hours of cooking. There is one other difference between the two methods.

Mrs. Freddie, a Hupa, pours water over ground acorns in a sand basin

The temperature at which you process the acorns at any point is critical. Boiling water or roasting over 165º F precooks the starch in the acorn. Cold processing and low temperatures under 150 F does not cook the starch. Cold-water leached acorn meal thickens when cooked, hot-water leached acorn meal does not thicken or act as a binder (like eggs or gluten) when cooked. Your final use of the acorns should factor in how you will process them. If you are going to leach and roast whole for snacking then boiling is fine. If you are going to use the acorn for flour it should be cold processed, or you will have to add a binder.

The finer acorns are ground the quicker they leach

Personally, I grind mine in a lot of water to a fine meal, let it set, then strain. I add more water to the meal, let set and strain. I do that until the water is clear or the meal not bitter. That takes a few days to a week. Then I dry it in the sun, unless there are squirrels about, then in a slow oven (under 150º F.) I end up with a meal or flour, depending on the grind, that will not crumble when cooked.

There are nearly as many variations to leach acorns as there are opinions about acorns. Another way is to put the shelled acorns in water in a blender or food processor and blend them into a milk-like slurry. Put that slurry in a fine mesh bag and then massage that under running water like a faucet. It works very quickly but of course some meal and oil is lost in the process. But it turns hours of leaching into minutes. Of course, leaching them in an unpolluted stream is the easiest way but you can also arrange for a container to leak slowly. Simply put a cloth on the bottom to hold the meal in and fill the container when it is empty, or run the faucet slowly to maintain the leaching. Another ways is to clean out the tank on your toilet and put the shelled acorns in a mesh bag in there. Every flush will remove tannic water and bring in fresh.

Acorn bread in a classic cast iron pan

Many Native Americans preferred bitter acorns to sweet ones because they stored better. If after leaching there is just a hint of bitterness that can sometimes be removed by soaking the acorns in milk for a while. The protein in the milk will bind with the tannin in the acorns and can be poured off, if there is just a little. To get oil from the cold-leached acorns, boil them. The oil will rise to the top of the water. Also, charred acorns can be used as a substitute for coffee but really nothing is a substitute for coffee.

Acorn grubs are edible raw or cooked

Whole leached acorns can be roasted for an hour at 350º F, coarsely ground leached acorns slightly less time. They can then be eaten or ground into non-binding flour. To make a flour out of your whole or coarsely ground acorns, toss them in a blender or food processor. Strain the results through a strainer to take out the larger pieces then reduce them as well. Acorn flour has no gluten so it is usually mixed 50/50 with wheat flour. Since acorn flour is high in oil it needs to be stored carefully and not allowed to go rancid. Remember cold processed acorn flour has more binding capacity than heat processed acorn flour.

Live Oak acorns top the food list for birds such as wood ducks, wild turkeys, quail and jays. Squirrels, raccoons and whitetail deer also like them, sometimes to the point of being 25% of their fall diet. Interestingly, the tannin tends to be in the bottom half of the acorn which is why you will often see a squirrel eat only the upper half of the acorn. Squirrels are also not fools. They will eat all of a white acorn when they find one because it is the least bitter. They will bury the very bitter red and black acorns so over time some of the bitterness is leached into the soil. Raiding a squirrel’s hoard will get bitter acorns. By the way, acorns shells and unleached nut meat have gallotannins which are toxic to cattle, sheep, goats, horses and dogs.

If you use the boiling method don’t throw away the tannic water. The water has a variety of uses. With a mordant it can be used to dye clothing. The tannic acid also makes a good laundry detergent. Two cups to each load but it will color whites temporarily a slightly tan color. Tannic water is antiviral and antiseptic. It can be used as a wash for skin rashes, skin irritations, burns, cuts, abrasions and poison ivy. While you can pour the tannic water over poison ivy, if you have the luxury freeze the brown water in ice cube trays and use the cubes on the ivy eruption. If you have a sore throat you can even gargle with tannic water or use it as a mild tea for diarrhea and dysentery. Externally dark tannic water can be used on hemorrhoids. Hides soaked in tannic water make better leather clothing. Using the brown water turned hides tan-colored and that is why it is called tanning and from there we get the words tannins and tannic. In traditional tanning methods, whole hides are soaked in a vat of tannin water for a full year before being processed.

Besides dyes paints have also been made from the oaks. It also a dense wood for working and weights 75 pounds per dry cubic foot. The hull of the US warship, USS Constitution, was made entirely of oak, white oak covering over a live oak core. At the waterline she was 25-inches thick. Eighteen-pound cannonballs bounced off the oak, notable in the 1812 battle with the HMS Guerriere. That battle and the subsequent loss of British ships caused the British to issue the order that no ship was to attack the Constitution singlehandedly. The Constitution, as of this writing, is still on duty and berthed in Boston.

Oak trees begin to produce acorns at about 20 years old but usually the first full crop won’t happen until the tree is about 50. The average 100-year old oak produces about 2,200 acorns per season. Only one in 10,000 will become a tree.

Peter Becker’s “Newtella”

Sprouted acorns are also edible as long as they haven’t turned green. I’ve heard from German forager Peter Becker who has a slightly different view of what to do with acorns.

“What I do to prep acorns for consumption is let them germinate, so the starches turn into malt sugar. I’ve only just developed a new product with acorns to introduce this precious nut to public because acorns are generally considered inedible here in Germany. NewTella is a sweet bread spread just like Nutella, the famous hazelnut creme, except that all ingredients are locally available, it has less sugar and the only fats are from the acorn. The basic preparation is to roast leached, peeled and germinated acorns, boil 1 part acorns with 3 parts of apple juice, when soft process them smoothly, add 20 % sugar with pectin. This bread spread is also a great way to preserve acorns and can be used for cookies. It’s a great way to promote this gigantic untapped resource and jazz up general nutrition.“

A few exchanges about Peter’s process is below in the comments. He shells them, leaches them (cold water) and sprouts them before using them to make his NewTella. That helps convert the starch to malt, which is sweet.

Older oaks with swelling.

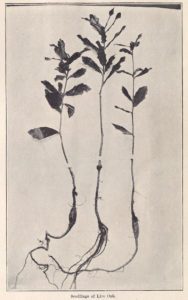

What about other parts of the oak? Get ready for some official hearsay… A century ago a pamphlet was published by a W.C. Coker on “The Seedlings Of The Live Oak and White Oak.” Coker referenced an article called “The Acorns And Their Germinations” by a Dr. Engelmann in Vol IV, 1880, of the Academy of Science of St. Louis. He in turn was referencing three fellows in South Carolina one of whom, William St. John Mazyck, made the original observation. Englemann wrote: “The structure of the acorns and the germination of the oaks seem to be so well-known, that I did not pay much further attention to it until my interest was excited by the information that the germination Live Oak developed little tubers, well-known to … children and greedily eaten by them….”

Is this oak seedling creating a starchy swelling that’s edible?

Essentially they write that after the acorn sprouts and sends up a young shoot the root develops a small elongated swelling that is edible. They agreed the swelling contains starch. The question they were discussing was when does the “tuber” form and how long does it last? They suspected it formed before the young shoot developed many true leaves. The swelling persists but grows woody in a few years. The “plate” in the pamphlet (above left) showed older oaks shoots but was used to show the swelling location when younger. One question was why would some species do this and the possible answer was hard times, or if you’re an oak, bad weather. The starchy swelling would help feed the seedling.

Lastly you may have a use for those acorns mentioned above that float when tossed in water. Most of them have a weevil grub in them, the Acorn Curculio. Look for a little 1/8 inch hole. In time that grub will crawl out and burrow into the ground for a couple of years turning into a full-fledged insect. You can use that grub in the acorn as bait for fish. Or, you can let it crawl in to a bucket of dirt or sawdust or a container of oatmeal where it will make a cocoon which you can then open later and use for bait. Store live in the frig. Also, squirrels like the grubs so it is not beyond reason to use them for bait for squirrels. And to answer your question, the grubs are edible by humans raw or cooked. I like them cooked in butter though bacon fat might do as well. You may also find a little worm with legs in an acorn. My entomologist friends tell them they are edible, too.

Acorn Bread

2 cups acorn flour

2 cups cattail or white flour

3 teaspoons baking powder

1/3 cup maple syrup or sugar

1 egg

1/2 cup milk

3 tablespoons olive

Bake in pan for 30 minutes or until done at 400 degrees.

A far more simple form of acorn bread is to make a thick acorn porridge out of cold processed acorn flour. Take a large tablespoon of the porridge and drop it into cold water. This causes the porridge to contract. Take the lump out of the water and dry.

Green Deane’s “Itemized” Plant Profile

Autum Acorns

IDENTIFICATION: Acorns, small nut with cap. Rough and larger caps belong to the more bitter acorns.

TIME OF YEAR: Usually late summer, fall, tree do not produce every year.

ENVIRONMENT: Oaks inhabit all kinds of environments.

METHOD OF PREPARATION: Numerous once leached of tannins.: out of hand, flour, candy.

HERB BLURB

The tannins have been used as an astringent as well as antiviral, antiseptic and antitumor but could also be carcinogenic. The mold that develops on acorns has antibiotic properties.