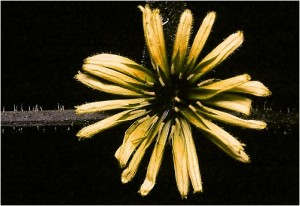

Chicory’s pale blue blosoms are also edible.

Cichorium intybus: Burned to a Crisp

Chicory was not a common plant where I grew up or where I’ve lived for 41 years. But I remember the first time I saw it, in 1990, in a park in Alexandria, Virginia, the bedroom of Washington DC.

What was so exciting was it was textbook perfect. The chicory looked exactly what it was supposed to look like, and that happens so rarely in foraging. That bears repeating: In my decades of foraging chicory is one of two plants I did not know which when I found looked exactly as they should have. That is one reason why pictures are not as good at identifying plants as people think. A good botanical drawing has all the essential elements in representative proportions and eliminates the unnecessary.

At any rate the chicory was instantly recognizable, growing next to a little ditch, and some of the flowers went home with me for my salad. I have since raised its bitter leafy cousins, radicchio and Belgian endive.

A friend of mine now passed was a luthier. Saul repaired very expensive instruments like Stradivarius and Guarneri violins. (Holding a million-dollar violin can make you very nervous.) He only drank coffee mixed with roasted chicory root, perhaps the most well-known use of the plant. While some call chicory a coffee extender or a substitute for coffee, it is more accurate to say it is a blend that changes the overall flavor profile. If they made chicory coffee decaffeinated I would drink more of it. Caffeine and I had a medical argument at mid-life. It won thus I avoid it.

Chicory has other uses than leading coffee astray. The young leaves are edible in salads, as are the aforementioned blossoms. The flower buds can be pickled and the roots boiled and eaten, though that may take several changes of water. Blanched spring growth (raised in the dark) are not bitter.

Originally from Europe, chicory is reported throughout all of North America though I personally have never seen it here in central Florida. In my father’s native country, Greece, it’s a common wild green and picked often. As a people, Greeks still forage for greens regularly. It is as much something they do as it is foraging is something American’s don’t do. Thus there is a wide attitude between these two peoples about wild edibles. I have cousins who would be offended by the idea of buying greens. And while their patches of land might be small and scattered they tend to them religiously.

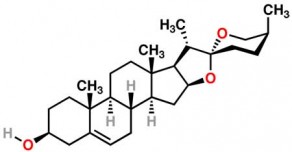

The botanical name, Cichorium intybus (see-KORE-ee-um IN-tye-buss) has a contorted history. Both words came through Greek then were bastardized by Latin. They are from ancient Persian and Egyptian for, respectively, chicory and its cousin, endive. The ancient Greeks called chicory Kichore but now use αντίδι (ahn-DEE-thee.) Intybus is from the Egyptian word “tybi” which means January, the month the vegetable was commonly eaten. But there is more to it. There was a lot of linguistic drift in the words Cichorium, chicory and Intybus. In fact, both Cichorium and chicory have the same root. Modern Greeks call it Radiki (rah-DEE-kee) the same word the use for dandelion greens.

The Greek horticulturist Dioscrorides called the large leaf version of the plant Seridos or Seris (what we would call endive.) The skinny-leaf version became kichore which eventually became the genus name, cichorium. That came from talkh shuky in Persian, meaning sour purslane. That changed to tarakhshaquq then kichore then cichorea in Latin (cichorium is the adjective form) and finally to chicory in English. Intybus is from tybi but it went from tybi to antubiya to hindaba to intybos to intybus to endivia and finally endive.

Green Deane’s “Itemized” Plant Profile

IDENTIFICATION: Perennial herb top five feet, large deep taproot, stems erect, often branching, leaves alternate, lance shaped broadest below the middle, to 12 inches long, three inches wide, toothed and lobed along the edge. Flowering heads up upper part of stems in the junction of smaller leaves, usually bright blue, sometimes pink or white.

TIME OF YEAR: Leaves as soon as possible in the spring, the root fall through spring. Flowers any time.

ENVIRONMENT: Like schalky soil but not fussy can be found along roads, fields, vacant lots, disturbed ground, gardens.

METHOD OF PREPARATION: Young leaves for salads, crown bases boiled five minutes, roots before stalk appears boiled in several changes of water, or roasted to mix with coffee, pickle flower buds, add open flowers to salads.