Waxy White Indian Pipes

Monotropa was almost a monotypic genus. Instead of having one species in the genus there were two: Monotropa uniflora and Monotropa hypopithys. Now they are two genera, Monotropa uniflora andHypopitys lanuginosa

Most references to the Monotropas are medicinal but Merritt Fernald in his publication “Edible Wild Plants of Eastern North America” mentions the Monotropa uniflora as barely edible. He writes on pages 305-306: “So far as we are informed, the only person who has reported upon it is Prest, who states the fresh plant is almost tasteless but that when parboiled and then boiled or roasted it is ‘comparable to asparagus.’ Our own single experiment was not gratifying in its result.”

Professor Merritt Fernald

That’s not promising. Fernald was the main botanical man of his age. Born in Orono, Maine, he was soon at Harvard and never left becoming the expert in eastern North American flora. He published the above book in 1943. Fernald died in 1950 two weeks shy of his 77th birthday. His book was republished in 1958. I own a copy. Nearly 40 years later in 1996 it was reprinted virtually unchanged. In the introduction, written during World War II, Fernald echoed some sentiments now familiar to us: “Nearly everyone has a certain amount of the pagan or gypsy in his nature and occasionally finds satisfaction in living for a time as a primitive man. Among the primitive instincts are the fondness for experimenting with unfamiliar foods and the desire to be independent of the conventional sources of supply. All campers and lovers of out-of-doors life delight to discover some new fruit or herb which it is safe to eat, and in actual camping it is often highly important to be able to recognize and secure fresh vegetables for the camp-diet; while in emergency the ready recognition of possible wild foods might save life. In these days, furthermore, when thoughtful people are wondering about the food-supply of the present and future generations, it is not amiss to assemble what is known of the now neglected but readily available vegetable-foods, some of which may yet come to be of real economic importance.”

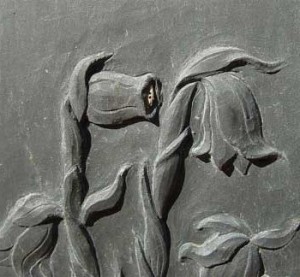

The blossoms turn down until seeding

Fernald thought little of the Monotropa uniflora and by accident or intent left out of his book’s bibliography who Prest was. That struck me as a challenge. I accepted. I eventually found a W.H. Prest who was the author of Edible Plants of Nova Scotia circa 1904-1905. He seemed a likely candidate. Experiment Station Record, Volume 23, United States Office of Experiment Stations, Agricultural Research Service, says on page 668 that Prest’s plant list was: “…a popular description of plants which have little commercial value, but which may be used for food in case of necessity.” More digging filled the name out to Walter H. Prest, of Bedford and Halifax, Nova Scotia. And it wasn’t much of a publication, just notes. They were included in the Proccedings of the Nova Scotian Institute of Science, Volume 11. Prest was a dues-paying member and participating fellow. On page 413 Prest gets to the Monotropa in note 67 (of 77) the first and only entry under “Parasitic Plants.” He writes:

Monotropa uniflora L. Indian Pipe, locally “Death-Plant.” White semitransparent stalk 2 1/2 in. to 5 in. high, with highly organized flower of five petals, without smell, stalk with thin transparent scales or leaflets, tender and almost tasteless. Parboil, then boil or roast, comparable to asparagus. In dry or moderately dry soil in thick woods, June to August. Generally distributed and abundant.”

Like Fernald, as far as I can tell Prest’s reference is the only reference to Monotropa uniflora’s edibility and perhaps the original that everyone now quotes via Fernald. At least we know Fernald copied it faithfully.

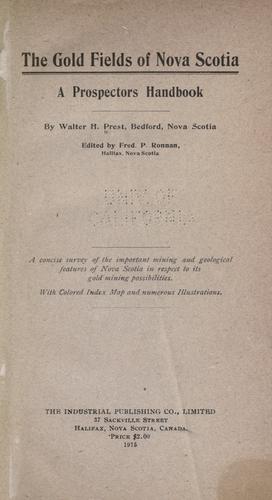

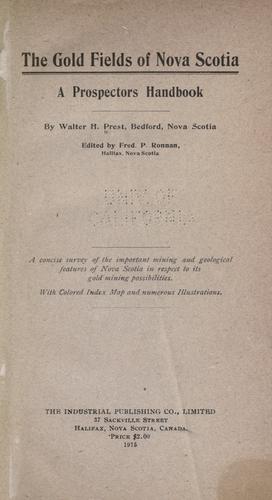

Prest’s Gold Mining Book

As for Prest, more than a century ago on page 387 of the proceedings introducing his list he wrote: “These notes on edible wild plants of Nova Scotia are the result of my early experience in the backwoods, and are offered with the hope that they may prove of benefit to those whom business or accident may lead temporarily beyond the reach of the resources of civilization. While some of the wild fruits here mentioned, such as the blueberry and cranberry, are of commercial value, others are included because they may assist in sustaining life at a critical time. While lost in the forest persons have perished through a want of knowledge of the resources which nature has bounteously provided in many sections at certain seasons of the year. As these resources are more animal than vegetable, the latter class has been much neglected. Therefore, the result to a lost man, unprovided with weapons or the means of snaring, trapping or catching game of fish, might be perhaps serious. I propose, therefore, to tabulate these edible plants, so far as known to me, and describe as freely and popularly as possible, all that have come under my personal notice….”

That’s another voice reaching across time about food. The next question would be who was Prest and what were his credentials? There might be an answer.

I don’t like articles with “holes” in them, missing bits of information whose absence irritates the reader. Call it the journalist in me but I wanted to know more about our single referencer. As far as I can tell he was Walter Henry Prest, born 1856 in Spry Bay, Nova Scotia, to Edward Isaac Prest and Ann Elizabeth McKinley. He married Maude Tuttle and died in Halifax in 1920. Prest — which is a variation of Priest — got out in the woods because

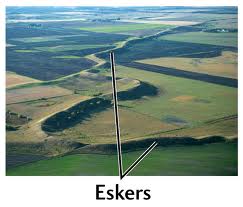

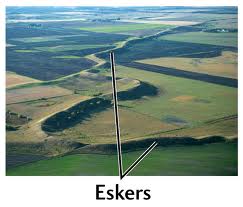

Eskers were once tunnels rivers flowed through under glaciers

he collected plants and was either a geologist or a gold prospector or both. He’s probably the author of “The Gold Fields of Nova Scotia: A Prospector’s Handbook” Halifax: Industrial Publishing Company, (1915). His original list of plants was published in 1901 in a small 23-page volume shared with another author on a different topic: Phenological observations in Nova Scotia and Canada, 1901 ; 2. Labrador plants (collected by W.H. Prest on the Labrador coast north of Hamilton Inlet, from the 25th of June to the 12th of August, 1901.) As mentioned earlier Prest was a member of the Nova Scotian Institute of Science and a year before he died read at least one paper there on the 12th of May 1919 “On The Nature and Origin of the Eskers of Nova Scotia.” An ekser is a long narrow winding ridge made up of layers of sediment and marks where there used to be a flowing tunnel through a glacier. Some are hundreds of miles long. That’s also where plants grow above the barren rock and where animals den.

Now we have a more complete picture of our forager. Prest had scientific grounding with a foot in geology, a foot in botany and some peer review. And if he knew about prospecting he was also out in the wilds a lot. Whether a long time without asparagus makes Monotropa uniflora as palatable as asparagus is another issue.

Hypopitys lanuginosa aka Monotropa hypopithys, Pinesap

The chlorophyll-less plant is widely distributed throughout most of North American and only absent from the southwest, intermountain west and the central Rocky mountains. Distributed yes but not commonly encountered. I see it now and then and never paid it much attention until I received an inquiry. It lives off fungi that get their energy from trees. Monotropa means “once turned” (the blossom turns before releasing seed) and uniflora means “one flowered.” The entire plant is waxy white. The other species in the genus is a bit of an issue.

Monotropia hypopithys, also called Pinesap, has the same growth pattern but instead of white it is yellow to gold and hairless in the summer, red and hairy in the fall. Dr. François Couplan in his book “The Encyclopedia of Edible Plants of North America” says on page 192 that M. hypopithys “is reported to be edible raw or cooked. It contains two glucosides, one of which yields by hydrolysis an essential oil containing methyl salicylate. The plant is antispasmodic and expectorant.” Sound more like medicine than food to me. It has also been renamed Hypopitys lanuginosa (lan-oo-gih-NO-suh) the latter meaning “wooly” or “downy.”

There is also a spelling issue with it, hypopithys or hypopitys. Books favor with the “H” and the Internet without, which suggests to me the books are right. More so, hypopithys/hypopitys is said to mean “under pines.” Linnaeus, who named the species, always used hypopithys as did Fernald, above, when Fernald rewrote and expanded Gray’s Manuel of Botany, which I have. As mentioned, I think there is something wrong in either the spelling, the translation or both. Then again, timing could also be an issue.

Boiled 15 minutes and still tasted bad

In Greek, modern or ancient, it is difficult to find the “H” sound associated with pines. Written language, after all, just reflects what people say. In Ancient Greek one word for pine was pitus, PEE-tus and one can see how that could be written in Dead Latin as pitys. No “H” as in hypopitys (high-poh-PIE-tees.) I would agree that means “under pines.” However, there was a wood nymph in Greek mythology named Pithys. Wood nymphs were called that because they stayed in the woods, also where Indians Pipes are found, only in the woods. Hypopithys (high-POH-pith-eez) would mean “under wood nymphs.” Linnaeus knew his Latin and Greek and consistently used the “H” in hypopithys. He was also the original dirty old man with a gutter sense of humor (you should read what naughtisms some of those botanical names translate into.) I suspect hypopithys, under wood nymphs, was the original naming, not as it has become referred to, hypopitys, under pines. Thus I think we had first the right spelling and the wrong translation; hypopithys, under wood nymphs mistranslated as under pines. Now we have the wrong spelling but the right translation of the wrong spelling, hypopitys, under pines and translated as under pines. Having read a lot of and about Linnaeus I think hypopithys, under wood nymphs, was more his frisky style.

Emily Dickenson, age 17

Both species are reported to be edible but because of the rarity of edibility reports and definite glucosides in the second species I would be careful. There might be a reason why only Prest says they are edible though he died nearly 20 years after writing that. If I find some more locally I’ll let you know.

I should also note the pale plant also drew the attention of Emily Dickinson, pale poet and closet romantic. In 1882, four years before Dickinson died, her neighbor, Mabel Loomis Todd, painted a watercolor of Indian Pipes as a gift to Dickinson.

Watercolor to gravestone

In a thank you letter to Mabel, Emily said, “That without suspecting it you should send me the preferred flower of life, seems almost supernatural… I still cherish the clutch with which I bore it from the ground when a wondering child, and unearthly booty, and maturity only enhances the mystery, never decreases it.”

In 1890 the same image of the Indian Pipes appeared on the cover of the first posthumous edition of Dickinson’s poems. The image was also reproduced on Mrs. Todd’s gravestone in Wildwood Cemetery in Amherst, Massachusetts.

Green Deane’s “Itemized” Plant Profile: Indian Pipes

IDENTIFICATION: Monotropa uniflora: From 10 to 30 centimeters. The entire plant is a translucent, “ghostly” white, sometimes pale pinkish-white and commonly has black flecks. The leaves are scale-like and flecked with black on the flower stalk (peduncle). As the Latin epithet uniflora implies, the stem bears a single flower. Upon emerging from the ground, the flower is pendant (downwardly pointed). As the anthers and stigma mature, the flower is spreading to all most perpendicular to the stem. The fruit is a capsule. As the capsule matures, the flower becomes erect (in line with the stem). Once ripened, seed is released through slits that open from the tip to the base of the capsule. The plant is persistent after seed dispersal. By the way, when the plant is unfertilized the “blossom” face down. When fertilized they point up.

TIME OF YEAR: Flowers from early summer to early autumn

ENVIRONMENT: Mature, moist, shaded forests in thick leaf litter.

METHOD OF PREPATION: Monotropa uniflora, parboiled, roasted or boiled. Monotropa hypoythis reportedly raw or cooked. Again, be wary of glucosides.

This original article was written by Green Deane in 2011.