The thermometer was near zero one day when I was on ice skates collecting frozen cranberries.

The cranberries were conveniently above the ice just waiting to be harvested. I was on the north end of “Gowen’s Pond” in Pownal, Maine. It was at that end where water seeped into the pond to make the couple of acres we skated on every winter. It was also there where I once went skating at 52 below zero… the things you do when you’re a kid and there’s a huge bonfire going. I got chilblained hands and feet that night. More than forty years later air conditioning still makes my hands and feet itch. (Yes, I now live in Florida and no, I do not have air conditioning.)

The water on that end of the pond wasn’t deep but it was moving so the ice could be shallow. Locals told a story about the farm next door that lost a cow through that ice one winter. I never did ask why the cow was out on the ice to start with. Maybe hungry and looking for cranberries.

The pond had one little island. Very little. One person couldn’t stand on it… more like a stump. But it was always above the ice and had a bush on it. As I skated past it I saw a movement. It was a turtle swimming under the ice eating a little greenery from around the island. ‘Cranberries and turtle,’ I thought. Actually that turtle was spared but it did make me realize early on that one can forage in winter if you know where to look.

Of course, the real issue is what kind of winter? That can range from deep snow and rock-hard frozen ground to only occasional cool days. Finding wild food where there is no snow and little or no freezing is not difficult. It’s finding food in gawd-awful winters that is a challenge.

I am fond of saying food is where the water is. Whether you are referring to your yard, your county, state, region or country, the farther away from water you are the farther away from food you are. While that is true all year perhaps it is most critical in winter. Plants and creatures can be found near water in the winter.

Everyone is familiar with or knows about ice fishing. In some northern areas it is not only a passion but a rite of passage. It can certainly put food on the table (as can hunting and trapping.) But not everyone has an ice hut or other equipment to harvest food that can move. In that case look for shallow, open streams or with ice than can be easily broken They have fresh water clams in the shallows. They don’t move too fast. As a young man I fished the Royal River in southern Maine and was always bringing home the clams I found. They are a bit tougher than those from the bay and occasionally one would yield a black pearl. I usually had a well-deserving lass to give it to.

Freshwater clams have to be handle carefully and cooked thoroughly but they are a good basis for a winter chowder. (The clams pick up parasites from land animal droppings requiring careful handling and cooking. Some clams are also federally protected so I’m sure you’ll check with local laws first.) Depending upon your stream or shallow pond you can also find crayfish and frogs (and turtles.) I should add that one of the advantage of aquatic turtles is that they do not eat toxic mushrooms. There is one instance where a person was sickened from eating a land turtle that had eaten mushrooms not toxic to it but toxic to humans.

Open streams or those with little ice can also produce cattail shoots and roots in winter. The shoots look like large dog’s teeth coming off the main root (actually horizontal rhizomes.) You can snap them off — and the end shoot — eating them raw or toss them into the clam chowder. The roots are also full of starch. Getting it out is labor intensive and I think overrated as a flour. However a more calorie positive way is just toss the roots on a fire. That burns off the covering and the muck they’re usually in. That also cooks the starch in the fibrous middle. Then you open up the root and pull the fibers through your teeth to get the cooked starch off. It tastes like chestnuts, and there are no pots to clean.

Also available stream side in winter are duck potatoes and groundnuts, the latter a good source of starch and protein. Duck potatoes grow deeper than groundnuts so they probably won’t be in any frozen banks but you do have to fish through cold water. Groundnuts are closer to the surface but still should be below the frost line or protected by water. That’s a toss up. The good thing about groundnuts is they are unmistakable. Nothing else looks like them. While stream side also look for watercress, a plant that likes cold water. It’s a peppery member of the mustard family. Often found in winter streams, it can be a flavoring and/or a green to put into that clam chowder.

If you live near the ocean there’s a lot of food available in winter. The natives used to say that when the tide was out dinner was on. Not only are there a wide variety of creatures to be had but sea weed as well. Most seaweed in northern climates is edible except for one variety in the pacific northwest that has sulfuric acid. If you mistakenly bite into Desmarestia ligulata you will know it. The problem with seaweed is most of it is not tasty but semi-drying and frying can help. If the weather is not too cold edibles can also be found hiding in the seaweed or on the rocks, such as crabs. One of the more odd things is that 50 years ago mussel at low tide were ignored except by us hungry latchkey kids. Now they are gourmet fare.

Depending on how cold and how much snow there are quite a few other edibles possible in winter. Sorrel can often last through a mild winter. Some radishes and wild mustards can take quite a freeze and stay alive and green as can any cabbage left over in your garden. Oyster mushrooms can be found anytime of the year even after warm weather has past. They don’t take freezing, however. Dandelions can survive the winter in snow but they undergo some chemical changes that make them more a famine food than a tasty find. Hardy little chickweed can germinate under snow so when the spring melt comes it is among the first green plants. Wild garlic and garlic mustard can can also be found in winter especially on south facing hills with little or no snow (so can some of the little mustards.) If there been no snow plantagos (plantains) can also be found in winter along with clover. But you have to be careful with clover. It can be a blood thinner. In some areas Stork’s Bill, (Alfilaria) is edible in winter. Just as a matter of routine south facing hills are always worth investigating for edibles particularly in the winter. Don’t forget to (carefully) roll over logs to find wintering lizards and or snakes. Colorful salamanders usually are NOT on the menu.

Just as I collected frozen cranberries don’t forget to look for rose hips, dried grapes and frozen wild apples (which are often better after freezing and cooking.) Hawthorn berries can persist into the winter as can persimmons, mountain ash, wild plums (sloes) various edible Viburnum berries and Rumex seeds still on the stalk. Partridgeberries are a common winter find as is wintergreen, which has edible berries and leaves for tea. Where I grew up I always found wintergreen with berries in the spring snow. It was years before I learned the berries over wintered. The little plant is also medicinal. Most persistent grass seeds are also edible. There are no toxic native North American grasses.

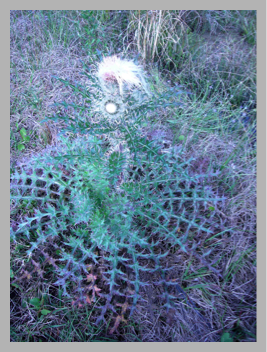

You can also eat the inner bark (cambium) of true pines (best fried in oil. Boiling is the least preferred means of preparation.) Pine needles can also be used for tea. Also edible is the cambium of the Sweet Birch (Betula lenta). It can be eaten raw or dried or cooked. It also preserves well. Most lichen — such as Reindeer Moss — is also edible. But it is a survival food that needs to have its acid leached out first and even then it’s a food of desperation. Lichen such as is better used as an antiseptic.There are more winter edibles but much depends upon the conditions. Acorns can be food but if they are covered with snow that doesn’t help much, and they will be frozen, and they need to be shelled, and they need to be leached and… well, you get the idea: Labor intensive in the best of times. The long skinny Burdock Root is edible but if the ground is frozen it can be a challenge to dig up as are Jerusalem Artichokes. Thistles, the kind that produces a large basal rosette with thorns that prick you like needles, also have an edible root raw or cooked. But the issue is whether the edible is buried in snow, and or is the ground granite hard?

In northern climates juniper berries can be used for flavoring… but not in the clam chowder. Juniper berries are used for bigger, gamey game… Elk and Moose come to mind…