A typical Tropical Almond in a typical setting. Photo by Tropical Plant Book

I went to Ft. Myers one Friday to look at plants on an 11-acre monastery. On the property there was a large tree they didn’t know nor did I. The following Sunday while teaching a class across the state in West Palm Beach two students knew a tree there that I didn’t know. It was the same tree at the Monastery. Small botanical world. The tree was a Tropical Almond.

Tropical Almonds at various stages of ripening. Photo by Staticd.

You would not know the Tropical Almond is not native to the American tropics if you judged it by popularity there. Starting in mid-Florida along the coast then south it becomes more common if not excessive by Central America. Not bad for a tree that is native to East Indies and related warm areas from Australia to Africa. It’s usually found in coastal locations because it likes low-elevation (under 1300 feet) and is salt, drought and wind tolerant. Add a lot of rain and no freezes and the tree is happy. It’s often used in landscaping because when a leaf dies it turns red making the tree colorful most of the time. The journey west to east probably started in Hawaii. We know it was there before 1800. It was definitely introduced to Jamaica by 1790. The tree is naturalized in southern Florida, the Florida Keys, Virgin Island and Hawaii as well as the West Indies and from Mexico to Peru and Brazil. It is also grown in warm areas of Texas and California

Pagoda-like Terminalia mantaly “Tricolor” in Hong Kong. Photo by Green State

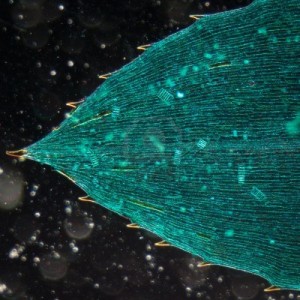

Botanically Terminalia catappa (ter-mih-NAIL-ee-uh kuh-TAP-uh) it is not related to the edible almond. No doubt the tree gets it common name from the seed pods which look like large unshelled three-inch almonds and from the seed/kernel which resembles almonds. Unlike true almonds though the outside of the fruit is also edible. Both the seeds and the fruit of this particular species are edible raw. When the fruit dries it is very light thus buoyant and uses water (ocean currents) to get spread around. They are a common “sea bean” found along Florida beaches. For such light fibrous things they are surprisingly tough to open (especially if you have only two chunks of small concrete as we did that day… the surface of Florida does not have rocks.) Julia Morton, who was a long-term botany professor at the University of Miami, reported in 1985 that “defleshed, thoroughly sun-dried fruits may be readily cracked by a sharp blow on the keel.” If well-dried they will also open if hit on the end point with a hammer.

Inside the Almond-like husk is a tasty kernel. Photo by N.I.T. Gallery

Propagated by seed the fast-growing Tropical Almond reaches 30 to 55-feet talls on average but can grow to 80 feet. Deciduous, it forms a symmetrical, upright tree with horizontal branches that reach 35 feet in width. The branches are arranged in tiers giving the tree a pagoda-like look. The tree’s large leaves are distinctive, 12-inches long and six-inches-wide, glossy green, leathery with a heart-shaped base. They are also woolly underneath and grow in a rosette at the end of branches. Leaf stems have two glands at the upper end. Before dropping from age, or winter or drought they change through shades of red, yellow, and purple. Spring time blossoms are inconspicuous, green and white, arranged in fives with 10 to 12 stamens each all on six-inch-long terminal clusters. They produce the edible fruit that changes through the colors already mentioned for the leaves: green to yellow then red or dark purple. The husk is corky, thin with green flesh inside. The fruit is high in tannic acid which can stain cars, pavement and sidewalks. But the tannic acid is also good for tanning hides. Interestingly the tree does not attract much wildlife. Some tropical ants like it and fruit bats eat the husk. Bees are attracted to the blossom but apparently have a difficult time making honey from them. Humans can barely detect an odor from the flowers. A tree can produce (when shelled) about 11 pounds of kernels per season.

There are some 250 species in the Terminalia genus. Terminalia is a variation of the Dead Latin word Terminus, a Roman God who presided over boundaries and frontiers. He liked fences and was never inside a buiding. In English we get termination, terminal and terminus from it. Here Terminalia refers to the rosette of leaves at the end of branches. While I would like to say Catappa is from the Greek word Kata (which means “below, all along” ) it is not. Catappa is variation of the Malaysian name for the tree which is ketapang.

Whether by age or conditions Tropical Almond leaves turn red making attractive foliage. Photo by J.M. Garg.

For flavonoids the tree has quercertin and kamferol; pigments include violaxanthin, lutein and zeaxanthin; tannins are punicalin, punicalagin and tercatein. The leaves and bark are astringent. Medicinally the tree has had a myriad of uses in folk medicine including treatment for cancer, sickle cell disorders, dysentery, cough, leprosy, nausea, diarrhea, intestinal parasites, eye problems, rheumatism, colic, liver disease, scabies, upset stomach, thrush and as an antibacterial agent and contraceptive. There is some modern research that suggests it might be useful in treating high blood pressure. Leaf extracts have shown to have some anti-diabetic and antioxidant activities. The leaves and bark are put in fish tanks to increase water acidity and reduce bacterial infections amongst the tank’s inhabitants.

Dried fruit floats and is carried thousands of miles by ocean currents. Photo by N.I.T. Gallery

The wood is moderately dense but had not been used for timber like other Terminalia species. It’s hard, strong, and has an attractive heartwood. Boxes, crates, buildings, bridges, boats, floors, planks, wheelbarrows, carts, barrels and water troughs are made from the wood. It does not do well in soil such as when used as fence posts but does well in water such as for building boats. In Fiji and Samoa it is the favorite wood for native drums.

A Tropical Almond Tree in India. Note the shallow roots, one reason why it grows well in south Florida which in many places only has a few feet of soil on limestone. Photo by Barbara E.

Related species that have edible kernels after washing and cooking are T. glabrata, T. litoralis, T. mauritiana, T. pamela, and T. kaernbachii, the latter of which has seeds that are 12.5 protein and 70% fat. Morton reported T. cattapa kernels are 52% fat, 25.5% protein and 6% sugar. The oil is mostly palmitic acid, 55.5% and oleic acid, 23%. Per 100 grams the outer flesh is 74% moisture, 5% protein and has 84 mg of calcium, 24mg of phosphorus, 7 mg iron, 21 mg of ascorbic acid. The T. cattapa is the only one in the genus to produce a kernel that can be eaten raw and does not need washing or cooking. A few species produce lesser quality fruit whose fleshy husks (but not seeds) are eaten: T. edulis, T. oblongata, T. platyphylla, T. sericocarpa, and T. solomonensis. The seeds of those species are often not eaten because of a high tannic acid content sometimes as high as 53%. Whether they can be leached like acorns I do not know. I suspect if they could it would have been discovered by now.

Tropical Almond fruit ripening. Photo by B. Navez

Other names for the species include: Barbados almond, bastard almond, Bengal almond, country almond, Demarara almond, false kamani, Fijian almond, Malabar almond, Malay almond, sea almond, Singapore almond, story tree, tavola nut, West Indian almond, alconorque, almendrillo, almendro, almendro de la India, almendron, almendro del pais, amandelboom, amandier de Cayenne, amandier des indies, amandier des tropiques, amendoeira, badam, badamier, castafia, castafiola, chapeu de sol, guarda-sol, kalumpit, kamani-haole, ketapang, kotamba, parasol, saori, talie, talisai, tavola, tipapop, tipop, tivi, white bombway, wilde amandel, zanmande, and many more dialect names.

The leaves are also fed to silkworms and animals.

Green Deane’s “Itemized” Plant Profile: Tropical Almond

Flowers of the Tropical Almond. Photo by J.M. Garg

IDENTIFICATION: Terminalia catappa: Usually a single trunk tree that can reach 80 feet high, 18 inches through at the base. It has whorls of nearly horizontal, slightly ascending, branches like pine trees eventually taking on a pagoda-like appearance. Branches droop at the tips. Leaves are short stemmed, spirally clustered at the branch tips, obovate, up to 11 inches long, six inches wide, dark-green above, paler beneath, leathery and glossy turning bright-scarlet, dark-red, dark purplish-red, or yellow in midwinter often right at Christmas time in Florida. In Hawaii the tree is evergreen. Foetid flowers are greenish-white, very small, no petals but 10-12 conspicuous stamens, in slender spikes in the leaf axils. Most flowers are male, a few hermaphrodite, some female. The fruit is two inches or more long, one inch or more wide. Most that I’ve seen are about three inches long and half as wide, ellipsoid more pointed at the end than at the base, slightly flattened, with a prominent keel around both sides and the tip. Skin is smooth, waxy, and thin. Pulp layer is juicy, whitish to pink or reddish, slightly sweet or acidic. The seed in the husk is spindle-shaped with a thin brown covering. The “kernel” is actually the tightly coiled seed leaves of the embryo, more tender than an almond with a hazel nut like flavor.

TIME OF YEAR: Varies on location, summer, winter or nearly all year. Here in Florida they bear in November. In southern Indian they have two crops per year. In the Caribbean they fruit continuously.

Young Tropical Almonds in pots. Photo by Tropicals USA

ENVIRONMENT: Full sun to medium shade on well-drained soil, tolerant of wind, salt, and drought, likes being mulched and regularly fertilized. Will not tolerate freezes. The germination rate for whole fruit is 25%. Seedlings are transplanted into pots and raised in shade slowly acclimatizing them to full sun. Field planting is done when they are seasonally leafless.

METHOD OF PREPARATION: The fruit has a pleasant aroma but is not too tasty. The ripe husks of the fruit can be eat raw but are best when young and sweet. The seeds have an almond or hazel-nut flavor. In India they are often served sitting in water on a small plate. The oil can also be used for cooking or to make soap. Leaves can be used as plates or to wrap small amounts of food. Among the fruit there can be a lot of variation as to when they are edible and palatable, sometimes when younger other times when older.

Tropical Almond Fruit. Photo by The Three Foragers