When I first heard of the Mahonias it was a bit irritating. They’re widespread shrubs in the western United States and here I was in Florida. But as time revealed, we have a Mahonia here, just not a native.

The berries of several Mahonias are edible in various ways including Mahonia aquifolium, Mahonia haematocarpa, Mahonea nervosa, Mahonia repens, Mahonia swaseyi, Mahonia trifoliolata and our local non-native Mahonia bealei, aka the Leatherleaf Mahonia. Their uses vary:

Oregon Hollygrape, photo by NameThatPlant.

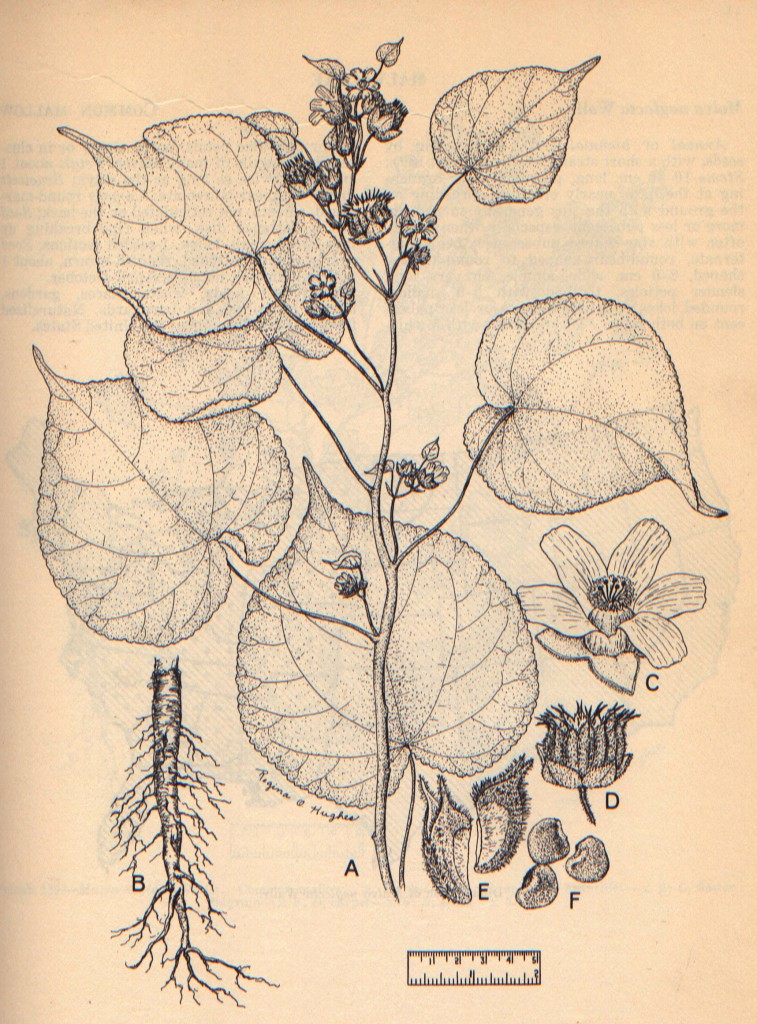

Mahonia aquifolium, the Oregon Hollygrape or Holly Barberry, has berries that are used in pies, jellies, jams, beverages and confections. Fermented they make a good wine. The yellow flowers are eaten or used to make a lemon-ade like drink. Mahonia haematocarpa, the Red Hollygrape, or Mexican Barberry, has blood red berries that are used to make jelly. Mahonea nervosa, is known as the Oregon Grape. It’s ripe fruit are too acidic to eat raw but are stewed with sugar or other fruits and or made into jelly or pies. They are used to help the flavor of milder fruits or to make a lemon-ade like drink. Young leaves are simmered in water and eaten as a snack.

Red Hollygrape, photo by Hirts Garden

Mahonia repens, the Creeping Barberry or Creeping Oregon Grape, has fruit that are eaten raw, roasted or pickled or made into jam, jelly, wine and or lemon-ade. A jelly made with half Mohonia juice and apple juice is common. Mahonia swaseyi, the Texas Mahonia, Agrito, Wild Currant and Chaparral Berry, has acidic yellow berries. They are used in juices, syrup, tarts, pies, wine, relish, candy and dried like raisins. Roasted seeds are a coffee substitute. Mahonia trifoliolata, Agrito, Laredo Mahonia and Mexican Barberry, has a subtle tart red berry eaten raw or used in jellies, preserves, sauces, drinks, cakes and tarts. Mahonia bealei, the Leatherleaf Mahonia and Beal’s Barberry, has berries edible raw or made into various thinks like pies, jelly and wine.

Texas Mahonia, photo by the Univ. of Texas

While most Mahonia are western natives the Leatherleaf Mahonia, from China, is a common and escaped ornamental in the South. It is shade tolerant and produces dense clusters of fragrant golden flowers in late winter or early spring. It’s a spiny gangly shrub usually planted on the north side of buildings where only it can tolerate the shade. Birds like the bluish-black berries so you have to be eagle-eyed to harvest them as they ripen. The berries also have a grayish-bloom. It arrived in Europe from China around 1800 and then to the United States. It is prohibited in Alabama, Georgia, Michigan, South Carolina and Tennessee. It is found from Florida to Maryland in coastal states asl well as Arkansas, Alabama, and Tennessee.

That said Mahonia of varying species can be found naturalized or native in most states and providences except states along the western bank of the Mississippi (excluding Arkansas). The USDA says Mahonias are also not found in Nebraska, Oklahoma, Mississippi, Tennessee, West Virginia, Hawaii, New England, Alaska, Yukon, Northwest Territories, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Newfoundland, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia.

There are about 70 species in the genus Mahonia (ma-HOE-nee-ah) which is named for the 19th century American horticulturist Bernard McMahon… makes one wonder why they left the Mc off… McMahonia… That can’t be any more un-Dead Latin than Shuttleworthii…Anyway… McMahon (1775-1816) was known as Thomas Jefferson’s “garden mentor” though there was quite a difference in their ages. Jefferson was 32 when McMahon was born and out-lived McMahon by 10 years. McMahon was born in Ireland but moved to Philadelphia in 1796 and opened a business in 1802, during Jefferson’s first term as president. He must of made himself known quickly. In fact it is said the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804-06 — authorized by Jefferson — was planned in McMahon’s home. And McMahon became one of the curator of the plants collected by the expedition when Lewis died in 1809. In 1806, three years before Jefferson left office and the year the expedition finished, McMahon published “The American Gardener’s Calendar” based heavily on previous English editions. But it recognized the harsher North American weather and advocated using natives for food and ornamental use. Jefferson was known to follow the directions in the calendar particularly regarding the planting of tulips and sea kale. McMahon died at 41 in 1816 seven years after Jefferson left office. In 1818 Thomas Nuttall bestowed the genus name of Mahonia on the west-coast evergreen shrubs that are still popular in planned gardens. The species name Bealei (BEEL-lee-eye) honors William James Beal (1833-1924) an American botanist who taught at the Michigan Agricultural College from 1870 to 1910… Or… it honors Thomas Chay Beale, consul from Portugal to Shanghai before 1860…. he grew plants collected by the great botanical spy Robert Fortune, responsible for smuggling tea seeds/plants out of China… Botanists also can’t agree on history.

A letter from Jefferson to McMahon about gardening still exists:

Monticello Jan. 13. 10.

Sir: Your favor of Dec. 24. did not get to hand till the 3d inst. and I return you my thanks for the garden seeds which came safely. I am curious to select only one or two of the best species or variety of every garden vegetable, and to reject all others from the garden to avoid the dangers of mixture & degeneracy. Some plants of your gooseberry, of the Hudson & Chili strawberries, & some bulbs of Crown imperials, if they can be put into such moderate packages as may be put into the mail, would be very acceptable. the Cedar of Lebanon & Cork oak are two trees I have long wished to possess. but, even if you have them, they could only come by water, & in charge of a careful individual, of which opportunities rarely occur.

Before you receive this, you will probably have seen Gen. Clarke the companion of Governor Lewis in his journey, & now the executor of his will. The papers relating to the expedition had safely arrived at Washington, had been delivered to Gen. Clarke, & were to be carried on by him to Philadelphia, and measures to be taken for immediate publication. The prospect of this being now more at hand, I think it justice due to the merits of Gov. Lewis to keep up the publication of his plants till his work is out, that he may reap the well deserved fame of their first discovery. with respect to mr Pursh I have no doubt Gen. Clarke will do by him whatever is honorable, & whatever may be useful to the work. Accept the assurances of my esteem & respect.

Th: Jefferson