Pacific Silverweed, a traditional vegetable.

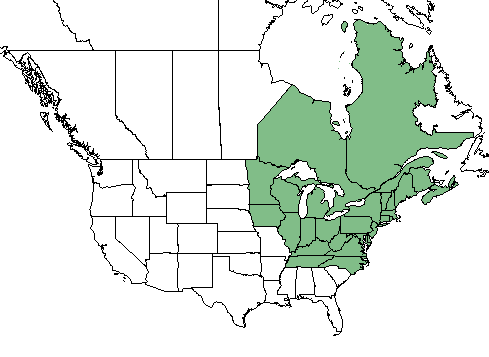

Pacific Silverweed gets around… mostly the top of the world: Siberia, Alaska, the Yukon, British Columbia, Nunavut, Ontario, Quebec, Newfoundland, Greenland… New Hampshire…( Mt. Washington is, after all, a mile high) western Long Island, Washington state, Oregon, California… And it has a long list of names: Silverweed, Pacific Silverweed, Greenland Silverweed, Eged’s Silverweed, Potentilla pacifica, Potentilla anserina ssp. pacifica, Argentina egedii ssp. ededii, Argentina egedii ssp. groenlandica and no doubt others. It was renamed in the 1990’s and not everyone is pleased. I think the nom de jour is Argentina egedii. What ever it is called many native groups ate it for a very long time proving botanists are not necessary.

Pacific Silverweed roots. Photo by Radix4roots

Pacific Silverweed also has a lot of things we need. Per 100 grams of steamed roots it has: 132 calories, 3.1 grams of protein, 0.6 grams of fat, 29.5 grams of carbohydrates, 9.5 grams of fiber. No vitamin C reported and barely any Vitamin A, 0.2 RE. The B vitamins are B1(thiamin) 0.01, B2 (riboflavin) 0.01 and B3 (niacin) 2.4 mg. The minerals line up: Phosphorus 109 mg, sodium 65 mg, magnesium 60 mg, calcium 37 mg, iron 3.5 mg, zinc and copper 1.1 mg each, and manganese 0.8 mg.

One of the problems with the plant is it grows like crazy. But if you’re hungry that’s great. At least 12 native groups in North America considered it a staple. They also ate A. anserina the same way (Silverweed, Common Silverweed and Silver Cinquefoil.) It’s a smaller plant and is found in wet places inland distributed sporadically throughout most of North America except the Old South.

As for the botanical names… What Argentina means is easy, “silvery.” “Anserina” is Dead Latin for “of the goose” either because it was fed to geese or the plant’s leaf shape reminded someone of a goose foot which is also what “chenopodium” means. In Sweden it is called Goosewort. “Egedii” took me far longer to sort out. But, I had an inspiration one day and found the answer on page 813 of a 72-year old book, Gray’s Manual of Botany, edited by Merritt Fernal. (If you’ve visited my website I’ve mentioned Fernald here and there.) Egedii honors Hans Poulsen Egede (1686 -1758) “the father of Greenland” (or in new Dead Latin, groenlandica.)

Green Deane’s Itemized Plant Profile

IDENTIFICATION: A low-growing perennial that spreads by creeping stolons. Leaves are pinnately compound, alternating, glossy green with very silver undersides. The five-petaled, five-sepaled flowers remind one of buttercups.

TIME OF YEAR: Fall

ENVIRONMENT: Beaches, dunes, sand flats, coastal estuaries, high tidal marshes, at or above the mean high tide. (When you consider New Hampshire only has 18.57 miles of coastline that’s quite a feet… feat. If you count every tidal nook and cranny it’s 235 miles.)

METHOD OF PREPARATION: The roots are always cooked — boiling or roasting — to remove bitterness. They can be dried before or after cooking for storage