Contemporary Hunter-Gatherer

An Australian study tells us that modern day hunter gatherers get 64% of their energy from things that move, 36% from plants, basically two thirds flesh, one third non-flesh. The creatures we eat are usually nutritionally dense. This does not hold true for plants. While plants can provide important minerals, vitamins, antioxidants and necessary trace elements most of them don’t pack a caloric punch. Many if not most plants take more energy to collect, prepare and consume then we get back in calories. Dandelion greens could be a classic example.

Dandelion Greens

We have to find the dandelion greens, pick them, clean them, and in a true survival situation find the fuel to cook them, something to cook them in and good water to cook them in. That takes a lot of energy and time. For that dandelion leaves offer us little, and while the root is edible it is quite bitter. Conversely, a starchy root that is edible raw, such as sea kale, Crambe maritima, would be a prime edible. It has a large root, particularly at the end of the growing season and is edible raw. It’s easy to find, easy to dig up. That’s energy positive. It’s a caloric staple. Unfortunately it does not grow in warmer climates but Bull Thistle does and is easy to find. They populate pastures. Sea Kale populates European shores and can be found on the California and Oregon coasts.

Blossoming Sea Kale

In a survival situation (frankly life in general) if you are not taking in more calories then you are expending to get food you are inching towards starvation. This is why we don’t climb a pine tree to get a teaspoon of pine nuts tasty and edible as they are. When one needs to forage caloric staples become the prime food focus right after animals.

After a recent class in West Palm Beach I was asked to compile a list of local caloric staples. It’s not quite as easy as one might think. In the south end of the state there are edible coconuts. On the north end no coconuts but some almost two-season bull thistles. In between there’s quite a smattering of calorie positive wild food. This list is not meant to be definitive and not necessarily in caloric order though generally it is.

Winged Yam must be cooked.

If I had to pick one local wild plant to top the list it would be the Winged Yam (Dioscorea alata.) It is the yam you buy in the grocery store just gone wild. Under cultivation they grow long and tubular and often over 100 pounds. Left on their own in untilled soil they get lumpy and usually weigh between five and 20 pounds. Easy to identify, the root is usually just a few inches below the surface thus it takes very few calories to dig them up. Not edible raw they do need to be cooked, boiled or roasted. But one would use them just like one would potatoes. Said another way every Winged Yam you see in the wild, on average, is like finding a 10-pound bag of potatoes. Also, it is slightly watery hence another name, the water yam. But that liquid serves a purpose. If you cut a root in half the water seals the uncooked half, preserving it. My video is here.

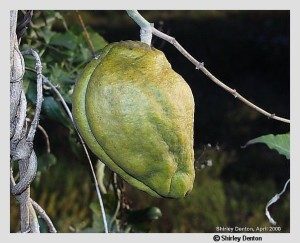

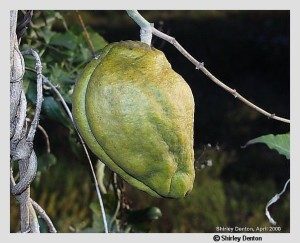

Milkweed Vine fruit tastes like potatoes and zucchini.

Next on the local menu is Milkweed Vine (Morrenia odorata). Resembling a chayote (Sechium edule) it has more vitamin C than the oranges it climbs over as a vine. Indeed, that is why Florida has spent millions of dollars to eliminate it, unsuccessfully. Nearly all of the plant above ground is edible but prized is the fruit. It should be picked when about the size of a tennis ball then boiled or roasted for about 40 minutes. The flavor is a cross between a zucchini and a potato. More to the point unless hit by a hard frost or a bad freeze the vine produces continually. Abundant, continuous production, nutritious and tasty. The fruit of the Milkweed Vine is a significant caloric staple. I have a video about it besides the article above.

Groundnuts also have to be cooked.

Third on my list would certainly be ground nuts, Apios americana, of which I also have two videos. Found nearly everywhere there is water east of the Rockies some people eat hundreds of pounds of them a year. Like the Bull Thistle ground nuts are nearly impossible to misidentify. The above- ground pea vine has leaflets of three, five, or seven, usually five sometimes nine. In the fall it has maroon pea-like flowers and puts on pods with edible seeds (cooked.) The nuts, actually tubers, are about the size of hens’ eggs, lumpy and brown, but they are arranged like a string of pearls. Lump then root, lump then root. They can fork and they do like to grow amongst other roots. But they are fairly easy to harvest and a full of calories and nutrition, and up to 26% protein. They must be cooked first, however. The greatest problem with ground nuts is they like to grow in the same locations as poison ivy so one has to be careful in their collection. And while they naturally elect to grow in damp spots they will readily grow in your normal vegetable garden. Video I here. Video II is here.

American lotus seeds are delicious cooked.

Fourth and highly seasonal is American lotus. There are two caloric staples with the American lotus, another plant that is nearly impossible to misidentify: The seeds and the roots. While the roots are edible like the lotus roots one finds in Asian markets, they are buried deep in the muck usually under several feet of water. Should the lake drain, they would be a staple worth going after, or if you have a backhoe. You could also cultivate them in shallow ponds. Otherwise we are interested in the seeds. When the seeds are ready to harvest literally thousands of shower-nozzle seed head can be gathered if you have something like a canoe and a knife. One person collects the other paddles. The seeds are like an elongated marble. They can be boiled like peanuts or roasted or dried et cetera. They do have a small green center (a tiny lotus plant) that is bitter and usually removed before eating the rest of the seed. Their flavor is very compelling, real food. Their video is here.

Bull Thistle roots is edible raw or cooked.

Fifth place would be the Bull Thistle, of which I have two videos as well. Like the yam it will have a larger root near the end of the season (or first year in northern climates) or at the very beginning of the second season before it uses the energy stored in the root to reproduce. The plant is nearly impossible to misidentify and all the members of the genus (Cirsium) are edible. The root is edible raw or cooked. As mentioned above the best place to find them are in pastures. Usually pastures are not polluted and about the only two plants uneaten are pawpaws, an occasional yucca, and bull thistles. Above ground parts are edible as well but require more work where as the root is fairly easy to dig up. It is calorie positive. Video I, and, Video II.

Cooked spurge nettle roots peels easily.

The Spurge Nettle should be added to the round up as well. Cnidoscolus stimulosus has a totally undeserved reputation for having roots buried very deep. In my several decades of foraging for them the root has always been within a foot below the surface. Here’s the problem: First, the root is brittle. Next it takes on a similar coloring of the ground it’s in. Third the root has a tap root that does go deep. So what happens is most folks actually throw the root away in the first few shovels of dirt then follow the tap root to great and unproductive depths because the root is buried under the dirt they have piled up. Boiled, peeled, and the center string removed, the al dente root tastes like pasta. My video is here.

Coconuts are nutritious but take a lot of work.

As this is Florida I would be remiss if I did not add coconuts to the list. The ones at the southern end of the state are indeed edible. But, like all coconuts they are a bit of work to get at. They are a source of food, water, transfusion liquid, fat, sugar and fiber. About the only down side to the coconut, besides a pain to open, is too much of the liquid is laxative. But coconuts bring up a problem that is associated with the next caloric staples, they take energy to get. In this case, climbing a coconut tree (make a pair of rope handcuff except to go around your feet, holding them together. That is how you use your feet to climb a coconut palm.) Again, like many of the caloric staples, the coconut is nearly impossible to misidentify.

Cattails produce more starch than any other plant.

Nothing produces more starch per acre under cultivation than cattails, more than 6,000 pounds. They are also nearly impossible to misidentify and can be found mostly east of the Rockies. Cattails have been called the supermarket of the swamp but I think that is excessive because their starch requires some work to get. First, you are likely to get wet getting the roots (actually rhizomes) and the roots are usually in some very smelly swamp muck. Personally I roast the roots which is getting the most (good tasting) caloric bang for the work buck. The starch can be crushed out of the roots and settled off with water but that takes time and energy best suited to a village setting, ample time, and many hands. More so unlike the items above cattail starch is much like flour, nearly tasteless unless cooked some way. The video is here.

Yellow Spatter Dock pods are full of edible seeds.

Yellow spatter dock seeds were a staple of the Klamath Indians of the Pacific Northwest. Despite glowing reports on the internet the root is not edible. However the properly prepared seeds are very tasty. Improperly prepared they are foul. I have warned you. Have patients with the seeds. Like American Lotus seeds, it is easy for one person in a canoe to collect a huge amount of seed pods at one time. You then put the seed pods in fresh water and let them rot for three weeks. Two weeks is not enough. You need at least three weeks of rotting to turn the bitter seeds sweet. Sometimes you can find some seeds that aren’t too bitter and can be cooked fresh but usually they are far better after the enzymes caused by the rotting have a chance to work their magic. If you cut a pod open you can see the kernels line up on either side looking like little yellow seed corn. Incidentally, dry and whole they pop like popcorn, only not as big. Sometimes they are not too bitter and can be cooked as is. And while several traditional foraging books say the root is edible it is not. Don’t believe me? Go get a root and cook it any way you choose (I’ve tried them all.) If you eat it be prepared to throw up. The video is here.

Processing acorns takes time.

There is no doubt that acorns are good food, once leached of their tannins. As I mention in the article Wild Flours it’s all about energy in and energy out. Whether acorns are calorie positive is a good debate. I suspect so but not by much. The reason is time. Collecting acorns goes fairly quickly, sorting out the potential good ones from the bad is easy. Drying them for a day or two in the sun requires little effort (though wildlife might try to steal a few.) What takes the time is shelling them. Putting them in the sun a few days helps but shelling is time consuming by hand (a good job for kids.) A mechanical nut sheller turns a job that takes hours into minutes and is worth the investment if you have a lot of acorns you can harvest. At this writing the shellers, which can be used on other nuts, run about $150. Once shelled the acorns need to be ground and then leached of their tannins. That can take a lot of time and energy depending on whether you are near fresh water or not. The bottom line is under good conditions acorns are calorie positive, under bad conditions a waste of time. Acorns were my fiftieth video.

Pine cambium is bland in flavor, edible raw or cooked.

For local and international consumption one has to mention pine cambium. As long as it is a member of the Pinus genus the white inner back is edible and very nutritious. A pound of pine cambium is like nine cups of milk. Not bad, and the flavor is not piney. The cambium can be eaten raw, dried, powdered and added to bread and soups, fried or boiled. Boiling is the least desired means of cooking and brings out the worst in pine cambium. Video here.

Wild Rice is a staple in many northern climates.

I would add wild rice to the list, and it is easily harvested, but not that much of it grows locally. It does grow here and there along the St. Johns but I’ve never found enough to harvest beyond a sample. In other areas it was a staple of Native Americans and is a sought-after gourmet food today. Like the Nuphar and Lotus seed pods, a person with a canoe can collect a lot of wild rice if he can find it. The usual method is to use one stick to bend the rice over the canoe and used the other stick to knock it off. You can then return to the same site a few days later and harvest again as not all the rice ripens at the same time. Wild rice also offers only a short window for harvesting, ten to fourteen days usually. It, too, requires some processing. If it is going to be one of your caloric staples you have to watch it very closely.

Barnyard Grass needs a lot of pounding to winnow.

Also in the grass realm is Barnyard Grass, (Echinochloa crus-galli.) Barnyard grass isn’t difficult to identify. It usually grows in very damp spots and has lower stems that are red/purple. It was a staple for many Indian tribes but is difficult to dehusk. The seeds require a lot of pounding before winnowing. On the positive side the plant can produce a crop in as little as 42 days. The key to the successful collection of Barnyard Grass involves finding a good size colony which should come into season all at the same time. One good place to find them is drying up holes in lakes low in water. Eastern Gamagrass can also be used.

Saw palmetto berries, strong flavored but nutritious.

One could add to the list Queen Palm Fruit (essentially mainline sugar like sugar cane) Pindo Palm fruit, (video) with sugar and pectin, and Crowfoot Grass seeds (Dactyloctenium aegyptium) small, but fragile and easy to collect. Add a palm grub or two and you have a balanced meal. And do I dare add Saw Palmetto berries, Serenoa repens? They do taste like vomit but are very nutritious, and the seed oil is good for cooking. Video here. Cabbage Palm fruit is also reported as a staple of local indigenous tribes but they are a lot of work. Personally I think they ate the paint-thin pulp off the fruit then sprouted them then used them. Video here.

Bunya Bunya seeds. Photo by Green Deane

PS: I wrote this original article about a decade ago. If I had one more possible stable to add it would be the seeds of the Bunya Bunya. The tree is an ornamental along the gulf coast and up the west coast of United States. When the “cones” are on the ground the seeds are edible (same with the Norfolk Pine.) The seeds are starchy, some times easy to get at and other times not. They are a good source of calories but not that common. Article here, video here.

There are several edible Acacia blossoms and several Acacia with other edible parts. Featured here is Acacia podalyriaefolia, or the Queensland Silver Wattle. The blossoms can be mixed in a light batter similar to elder flowers and fried into small fritters. They are often served with sugar and whipped cream. Other Acacia with edible blossoms include A. spectabilis and A. oshanessii. While a native to Australia it is naturalized in Malaysia, Africa, India and South America. It is also used as an ornamental tree in other areas.

There are several edible Acacia blossoms and several Acacia with other edible parts. Featured here is Acacia podalyriaefolia, or the Queensland Silver Wattle. The blossoms can be mixed in a light batter similar to elder flowers and fried into small fritters. They are often served with sugar and whipped cream. Other Acacia with edible blossoms include A. spectabilis and A. oshanessii. While a native to Australia it is naturalized in Malaysia, Africa, India and South America. It is also used as an ornamental tree in other areas. The flower buds of the Syzygium aromaticum is your common clove, dried. They are used for seasoning with ham, sausages, apples, mincemeat, cheese, pies, preserves, and vermouth. In some places cloves are chewed after dinner like a mint. The oil is used to flavor gum, beverages, ice cream, baked goods, and candies. What most folks don’t know is the tree’s fruit is edible as are its dried flowers. A close relative S. malaccense, has edible flowers as well as young shoots and leaves.

The flower buds of the Syzygium aromaticum is your common clove, dried. They are used for seasoning with ham, sausages, apples, mincemeat, cheese, pies, preserves, and vermouth. In some places cloves are chewed after dinner like a mint. The oil is used to flavor gum, beverages, ice cream, baked goods, and candies. What most folks don’t know is the tree’s fruit is edible as are its dried flowers. A close relative S. malaccense, has edible flowers as well as young shoots and leaves. One cannot write about edible flowers without mentioning the Lotus, Nelumbo nucifera, also called Pink Lotus, Chinese Lotus, and Lin ngau. This is the plant that produces the famous roots in so many Asian dishes. Its roots can be boiled, pickled, stir-fried even preserved in sugar. The seeds are also eaten raw, roasted, boiled, pickled or candied. What a lot of foraging books don’t tell you is 1) the roots are really labor intensive to dig up, and 2) the blossoms are edible. The petals are used as garnishes or are floated in soups.

One cannot write about edible flowers without mentioning the Lotus, Nelumbo nucifera, also called Pink Lotus, Chinese Lotus, and Lin ngau. This is the plant that produces the famous roots in so many Asian dishes. Its roots can be boiled, pickled, stir-fried even preserved in sugar. The seeds are also eaten raw, roasted, boiled, pickled or candied. What a lot of foraging books don’t tell you is 1) the roots are really labor intensive to dig up, and 2) the blossoms are edible. The petals are used as garnishes or are floated in soups. Closely related to the lotus is Nymphaea stellata, also called the Blue Lotus of India. That it can be white shall be overlooked for now. Its roots are sometimes eaten raw or roasted. The seeds are edible as well, usually parched. The flowers are edible. And as so often the case, botanists cannot leave the name alone. The Blue Lotus of India is also known as Nymphaea nouchali. Now, doesn’t that make more sense?

Closely related to the lotus is Nymphaea stellata, also called the Blue Lotus of India. That it can be white shall be overlooked for now. Its roots are sometimes eaten raw or roasted. The seeds are edible as well, usually parched. The flowers are edible. And as so often the case, botanists cannot leave the name alone. The Blue Lotus of India is also known as Nymphaea nouchali. Now, doesn’t that make more sense? I can’t remember if it was Ray Mears or Les Hiddins who first brought my attention to the Pandanus, or in this particular case Pandanus tectorius. The Pandanus is a palm. It’s also called the Nicobar Breadfruit and Screwpine. The fruit pulp can be eaten raw or cooked or made into a flour. It’s also used to make a local alcoholic drink. Young leaves are eaten as are the aerial roots, terminal bud and seeds. The flowers and pollen are edible as well. Native from Malaysia to Polynesia, it is an ornamental in warmer areas elsewhere. I’m reasonably sure there is a stand of them growing in Dreher Park, West Palm Beach. Fl., but I haven’t sorted out which species it is.

I can’t remember if it was Ray Mears or Les Hiddins who first brought my attention to the Pandanus, or in this particular case Pandanus tectorius. The Pandanus is a palm. It’s also called the Nicobar Breadfruit and Screwpine. The fruit pulp can be eaten raw or cooked or made into a flour. It’s also used to make a local alcoholic drink. Young leaves are eaten as are the aerial roots, terminal bud and seeds. The flowers and pollen are edible as well. Native from Malaysia to Polynesia, it is an ornamental in warmer areas elsewhere. I’m reasonably sure there is a stand of them growing in Dreher Park, West Palm Beach. Fl., but I haven’t sorted out which species it is. The name Turpentine tree, Pistacia terebinthus, does not sound too edible. Perhaps it all depends upon where you live and how hungry you are. Actually it has an esteemed relative we eat all the time. Native to the Mediterranean region, the turpentine tree is in the same genus as the Pistachio. Its green seed kernals are eaten or pressed for their oil. The immature fruits are preserved, usually in vinegar and salt, and used as a relish. Young leaves are cooked and used as a vegetable. The sap is used to make a chewing gum and the fresh flowers are edible raw. Some caution should be used as this tree, like pistachios, is closely related to poison ivy/oak and poison sumac, along with cashews and mangos. Many people are allergic to the entire group.

The name Turpentine tree, Pistacia terebinthus, does not sound too edible. Perhaps it all depends upon where you live and how hungry you are. Actually it has an esteemed relative we eat all the time. Native to the Mediterranean region, the turpentine tree is in the same genus as the Pistachio. Its green seed kernals are eaten or pressed for their oil. The immature fruits are preserved, usually in vinegar and salt, and used as a relish. Young leaves are cooked and used as a vegetable. The sap is used to make a chewing gum and the fresh flowers are edible raw. Some caution should be used as this tree, like pistachios, is closely related to poison ivy/oak and poison sumac, along with cashews and mangos. Many people are allergic to the entire group. Attractive ornamentals are often toxic but not the Clematis maximowicziana, or Sweet Autumn Clematis, a popular vine among gardeners in North America. What I find interesting is how often English or country garden sites often just lable every plant they grow as poisonous. It must just come with the mind set. The Sweet Autumn Clematis is definitely edible. Young leaves are parboiled then are boiled or stir fried. Young buds are used the same way or pickled. The flowers are also edible. Yet like so many internet sites that copy each other one says for them all: All parts of plant are poisonous if ingested. Perhaps if eaten raw they are. Cooked they are not which is good as this is a popular garden specimen.

Attractive ornamentals are often toxic but not the Clematis maximowicziana, or Sweet Autumn Clematis, a popular vine among gardeners in North America. What I find interesting is how often English or country garden sites often just lable every plant they grow as poisonous. It must just come with the mind set. The Sweet Autumn Clematis is definitely edible. Young leaves are parboiled then are boiled or stir fried. Young buds are used the same way or pickled. The flowers are also edible. Yet like so many internet sites that copy each other one says for them all: All parts of plant are poisonous if ingested. Perhaps if eaten raw they are. Cooked they are not which is good as this is a popular garden specimen. Buttercups are usually a family foragers stay away from. It was one of the few flowers I was told as a kid that were poisonous that really are. They grew in a damp spot right behind the house. But not every one in the family will make you ill. Among the edible members is Ranunculus bulbosus, also called St. Anthony’s Turnip. I don’t know if that is a compliment to St. Anthony or not. Caution is recommended as the plant can have a strong, acrid juice that can cause blistering. Bulbs of the plant are eaten after boiling or thorough drying. The young flowers are pickled. In North America the plant is found in the eastern US except for Florida, and also growing along the west coast. It skips Texas north, the high plains, Rocky Mountains and desert southwest.

Buttercups are usually a family foragers stay away from. It was one of the few flowers I was told as a kid that were poisonous that really are. They grew in a damp spot right behind the house. But not every one in the family will make you ill. Among the edible members is Ranunculus bulbosus, also called St. Anthony’s Turnip. I don’t know if that is a compliment to St. Anthony or not. Caution is recommended as the plant can have a strong, acrid juice that can cause blistering. Bulbs of the plant are eaten after boiling or thorough drying. The young flowers are pickled. In North America the plant is found in the eastern US except for Florida, and also growing along the west coast. It skips Texas north, the high plains, Rocky Mountains and desert southwest. The 200th edible flower in this series is the Quince, one of my mother’s favorites, Cydonia oblonga. She has a flowering Quince right outside her front door and delights in watching birds nest in it. She also likes to complain about its thorns. Quince used to be a common fruit a century ago but needed to be prepared. Even the great botanist Luther Burbank said before he began breeding better cultivars to make them more edible, “take one quince, and barrel of sugar and sufficient water…” While quinces have fallen out of favor in the United States they are still popular elsewhere particularly in the Mediterranean region. The fruits are cooked, stewed, used in pies, jams or marmalades, fruit leather, candies and conserves. The flowers are also edible and in some places the leaves are used to wrap food like Greek dolmas.

The 200th edible flower in this series is the Quince, one of my mother’s favorites, Cydonia oblonga. She has a flowering Quince right outside her front door and delights in watching birds nest in it. She also likes to complain about its thorns. Quince used to be a common fruit a century ago but needed to be prepared. Even the great botanist Luther Burbank said before he began breeding better cultivars to make them more edible, “take one quince, and barrel of sugar and sufficient water…” While quinces have fallen out of favor in the United States they are still popular elsewhere particularly in the Mediterranean region. The fruits are cooked, stewed, used in pies, jams or marmalades, fruit leather, candies and conserves. The flowers are also edible and in some places the leaves are used to wrap food like Greek dolmas.