I have a close friend who’s Cajun. He said his family was so poor growing up in the bayou that if it moved they cooked it and threw it on rice. That included Nutria, or as a good portion of the world calls it Coypu.

You can think of the Nutria as a large rat or a beaver with a small tail. Indeed the Italians call it Castorino (little beaver) the Dutch Beverrat (beaver rat) and the French, Ragondin. It’s been on the menu in its native South America ever since man was hungry. It got to most other countries as part of the fur trade, and that’s where the name became confusing. “Nutria” is actually the Coypu’s fur and for several different decades in the 1900s it was popular. In North America, particularly Louisiana where the rodent is a pest, it is called Nutria. The unwanted water resident has had a long history.

First introduced in California in 1899 between then and 1940 they were imported for fur use not only California but Washington, Oregon, Michigan, New Mexico, Louisiana, Ohio, and Utah. When the Nutria Fur trade collapsed in the United States in the early 1940s business owners simply let the animals go free. State and federal agencies as well as individuals relocated Nutria in the 1940s to Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Louisiana, and Texas to control vegetation. Always a dollar to be made these nocturnal vegetarians were also sold to the public as “weed cutters.”

Louisiana became ground zero when the state intentionally introduced 20 Nutria into marshes there in 1938 and made them a protected species while promoting them as biological agents for controlling aquatic weeds, primarily water hyacinth, an invasive that arrived there in 1876. Further Tabasco sauce tycoon E.A. McIlhenny imported some Nutria from Argentina in the 1930s for a fur farm. Some of his Nutria “liberated” themselves during hurricanes in 1937 and 1941 but the main escalation happened when Nutria fur market crashed soon after. It is estimated that Louisiana fur farmers released about 150 animals. Those in northern Louisiana did not survive their first cold winter but those in the southern part of the state did. By the mid-1950s those few animals had some 20 million descendants calling Louisiana home and causing huge environmental damage. In 1958 the marsh muncher was taken off the protected species list. For the next three decades the state promoted the animal as a source of fur. Some 1.3 million of them were taken each year mostly for fur use in Europe but that market began to wane with the anti-fur movement in the 1980’s. As an alternative Louisiana then promoted Nutria consumption knowing Cajuns are palate to palate with the Chinese on culinary adventurism.

Nutria are still damaging 7,000 acres of wetlands in Louisiana. They have been reported in at least 40 states and three Canadian provinces adjacent to the U.S. They are in many ways a curious creature. Mama Nutria has mammary glands on her sides so the little ones can nurse nose above water while floating. They are ready to start their own family at age four month and pregnant 80% of their lives, essentially they mate for life, just with different mates. As a species about 70% of them don’t make through even one year. In the wild a three-year-old Nutria is ancient. In captivity they can live 15 to 20 years. Besides man alligators, eagles, ospreys, turtles, snakes and several carnivores find them quite acceptable for dinner.

Nutria have short legs and highly arched body that is approximately two-feet long. Their round tail is a little over a foot long with little hair, average weight is 12 pounds but they can plump up to 20 pounds, sometimes 30 to 40. Their dense grayish underfur is overlaid by long, glossy guard hairs that vary in color from dark brown to yellowish brown. Forepaws have four well-developed, clawed toes and one vestigial toe. Four of the five clawed toes on the hind foot have webbing. A fifth outer toe is free. The hind legs are much larger than the forelegs giving them a humped look particularly on land. Like beavers, Nutria have large incisors that are yellow-orange to orange-red on their outer surfaces. They are very well adapted to aquatic life.

Nutria are almost entirely vegetarians and only eat animal material by mistake, such as insects on the plants they feed on. Freshwater mussels and crustaceans are occasionally eaten. Gluttons, they eat approximately 25% of their body weight daily and prefer several small meals to one large one. The plump base of plants are preferred as food, but they will not pass up choice entire plants or several different parts of a plant including roots, rhizomes, and tubers. Important food plants in the United States are cordgrasses (Spartina spp.), bulrushes (Scirpus spp.), spikerushes (Eleocharis spp.), chafflower (Alternanthera spp.), pickerelweeds (Pontederia spp.), cattails (Typha spp.), arrowheads (Sagittaria spp.), and flatsedges (Cyperus spp.). In winter, the bark of trees such as black willow (Salix nigra) and baldcypress (Taxodium distichum) may be eaten. They also eat crops and lawn grasses found adjacent to aquatic habitat. Like raccoons they have quite dexterous front paws. They leave tracks that are four-toes and webbed, often with a tail dragging mark. Dropping are long, cylindrical and grooved.

When trapping them cracked corn is the preferred bait along with sweet potatoes and carrots. Floating the trap on a raft eliminates capturing most other animals. Nutria, like rabbits, can carry Tularemia. Trapping regulations vary state to state. In some states no license is needed for live traps and live animals cannot be returned to the wild. If you are hunting them after dark you have to be careful where you shoot them or they will sink out of sight. Less humanely they can also be taken with gigs on very long poles, or clamp traps. The state of Maryland has been waging a war with Nutria since 2002 in the Chesapeake Bay region. By November 2011 it had killed some 13,000 of them and was trying to eliminate small remaining pockets. As of 2016, all of the known Nutria populations had been removed from over a quarter million acres of the Delmarva Peninsula but the wetland may take another 40 years to recover from the damage. Also called Bayou Rabbit, Nutria can be found not only in North America but Europe, the Soviet Union, the Middle East, Africa, and Japan. They have been introduced to every continent except Antarctica and Australia.

Scientifically the water rat in North America is known as Myocastor coypu var. bonariensis. There is only one genus and one species — monotypic — but there are four variations. The genus is two Greek words mashed together to mean Mouse Beaver. Coypu is what the Mapuche Indians of Chile and Argentina called it though typical of Dead Latin their “Koypu” was changed to Coypu. This is the same part of the world that gave us Araucana chickens which lay light green eggs and the Aracarua araucana, and the Monkey Puzzle Tree which has pine cones the size of softballs and edible seeds.

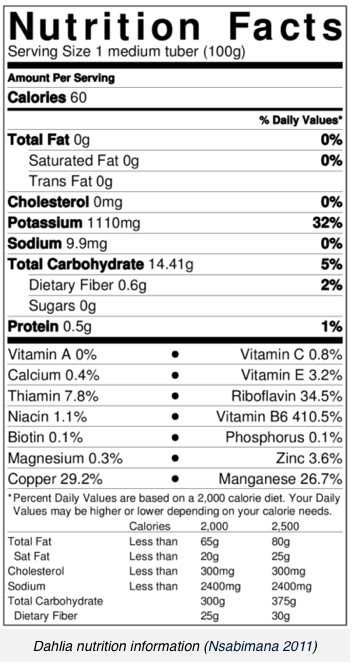

While Nutria meat can be cooked a wide variety of ways it can be on the tough side thus improves with low, moist heat. One common meat it is compared to is rabbit though the taste is closer to dark turkey meat. According to a state analysis, raw Nutria meat has more protein per serving than ground beef and is much lower in fat than farm-raised catfish.

The recipes are from Nutria.com, a site sponsored by the state of Louisiana. Below the recipes is a round up of Nutria in Europe.

Heart Healthy ‘Crock-Pot’ Nutria

|

2 hind saddle portions of nutria meat

1 small onion, sliced thin

1 tomato, cut into big wedges

2 potatoes, sliced thin

2 carrots, sliced thin

8 Brussels sprouts

1/2 cup white wine

1 cup water

2 teaspoons chopped garlic

Salt and pepper to taste

1 cup demi-glace (optional)

Layer onion, tomato, potatoes, carrots and Brussels sprouts in crock pot. Season nutria with salt, pepper and garlic, and place nutria over vegetables. Add wine and water, set crockpot on low and let cook until meat is tender (approximately 1-1/2 hours). Garnish with vegetables and demi-glace. Makes four servings.

Nutria Chili

Recipe by: Chef Enola Prudhomme

3 tablespoons vegetable oil

2 pounds nutria ground meat

1 tablespoon + 1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon red pepper

1 tablespoon + 1 teaspoon chili powder

1 cup diced onion

1 cup diced green bell pepper

1 cup diced red bell pepper

1 cup tomato paste

4 cups beef stock (or water)

1 can red kidney beans (opt.)

In a heavy 5-quart pot on high heat, add oil and heat until very hot. Add nutria meat, and cook and stir 10 minutes. Add salt, red pepper, chili powder, onion and both bell peppers. Cook and stir 15 minutes. Add tomato paste and 4 cups stock. Cook 30 minutes; reduce heat to medium. Add red kidney beans; cook an additional 10 minutes. Serve hot!

Enola’s Smothered Nutria

Makes 4 Servings

2 tablespoons vegetable oil

1-3 pound nutria, cut in serving pieces

2 tablespoons Enola’s Secret Seasoning + 2 teaspoons

2 cups finely chopped onion

1 cup finely chopped green bell pepper

1 tablespoon flour

1 teaspoon salt (opt.)

3 3/4 cups chicken stock or broth

In a heavy 5-quart pot on high heat, add oil, heat until very hot. Sprinkle seasoning on meat; stir well. Add meat to pot, brown on all sides. Cook and stir 10 minutes. Add onion, bell pepper and flour, cook and stir 10 minutes. Add salt and chicken stock to pot cook and stir occasionally, (about 15 minutes) scraping the bottom of pot to remove all the goodness. Serve over hot cooked rice, pasta or cream potatoes.

Ragodin au Choux Rouge

(Nutria with caramelized red cabbage and honey mustard sauce)

2 hind saddle of nutria (available at Calvin’s Bocage Supermarket)

1/3 cup chopped celery

1/3 cup chopped onion

1/3 cup chopped carrots

Bouquet garni

1 branch french thyme, 1/2 bunch of parsley, 2 fresh bay leaves

1 1/2 teaspoons vegetable oil,

2 teaspoons flour

4 teaspoons Dijon mustard and 1/2 cup honey

1 cup red wine

1 teaspoon olive oil

1/2 teaspoon crushed fresh rosemary

2 cups hot water

Season to taste

Caramelized choux rouge: 1 thinly sliced red cabbage, _ cup sugar, 1 teaspoon vegetable oil, season to taste.

Saute red cabbage with oil, sugar and seasoning until sugar is caramelized (4 to 5 minutes).

Place oil, chopped vegetables and bouquet garni in a large saute pan. Rub each hind saddle with mustard, honey and rosemary. Place hind saddle into large saute pan with the vegetable and saute on medium high heat, until golden brown, sprinkle flour and stir will until flour disappears, deglaze with red wine, stir well then add hot water, simmer on low heat for 1 – hours. Remove hind saddle, strain juice into a sauce pot, bring to a low boil, skim the fat off of surface, add cream, reduce for 5 minutes and correct seasoning. Remove meat from bones and plate, top with sauce, garnish with caramelized red cabbage.

Nutria Sausage

Recipe by: Chef Enola Prudhomme

2 pounds nutria meat

1 pound pork meat

10 1/2 ounces potato, peeled

2 1/4 teaspoons salt

2 teaspoons Enola’s Secret Seasoning (or Creole Seasoning)

1 teaspoon sage

Ground nutria and pork with potato. Add all other ingredients mix well. If using a

bar-b-que pit to smoke, build fire on one side of pit. Place sausage on the other side of pit; this will allow smoke to get to sausage without cooking to fast. If you have used bacon fat, put on your fire this will create lots of smoke. This will take less time to get a good smoketaste. Let sausage smoke 1 hour and 15 minutes; turn, let smoke 1 hour; remove from pit; letcool. Makes 4 pounds 5 ounces.

Stuffed Nutria Hindquarters

Recipe by: Chef Enola Prudhomme

Stuffing for nutria:

3 tablespoons butter

1 pound nutria meat, ground

4 cups chopped onion

1 cup green bell pepper

1 cup red bell pepper

1/4 teaspoon red pepper

2 1/2 teaspoons salt

1 teaspoon Enola’s Secret Seasoning (or Creole Seasoning)

1 cup stock or water

1 10 3/4 ounce can cream of mushroom soup

2 cups fresh Louisiana crawfish, peeled, deveined and chopped

13 slices of bread (stale)

Preheat oven to 350 degrees. Put bread in food processor; press pulse button several times. Bread crumbs must be course; set aside.

In a 5-quart pot on high heat melt butter. Add meat, onion and both bell peppers, cook and stir 10 minutes. Add red pepper, salt and seasoning; cook 5 minutes. Add stock; cook stirring occasionally for 10 minutes. Reduce heat to medium. Add cream of mushroom; cook for 7 minutes. Add crawfish, reduce heat to medium, and cook 5 minutes. Remove from heat, add bread crumbs, stir until mixture is moist but holds together.

Preparation of hindquarters:

15 nutria hindquarters

5 tablespoons Enola’s Secret Seasoning

Remove the large leg bone, then pound out legs, sprinkle seasoning evenly on both sides. Lay leg flat, stuff inside, roll and tie with cooking string. Place stuffed legs in oiled baking pan. Bake at 350 degrees covered, cook for 1 1/2 hour or until tender. Uncover; cook an additional 10 minutes or until brown. Makes 15 servings.

Smoked Nutria and Andouille Sausage Gumbo

Recipe by Brian Berry from Hotel Acadiana’s Bayou

Bistro

2 smoked nutria, cut into serving pieces

1/2 pound sliced andouille sausage

1 cup vegetable oil

1 1/2 cups flour

2 cups chopped onion

1 cup chopped celery

1 cup chopped bell pepper

1/4 cup diced garlic

3 quarts chicken stock

2 cups sliced green onions

1 cup chopped parsley

salt and cracked black pepper to taste

In a two gallon stock pot, heat oil over medium high heat. Once oil is hot, add flour. Using a wire whisk, stir until roux is golden brown. Do not scorch. Should black specks appear, discard and begin again.

Add onions, celery, bell pepper, and garlic. Saute approximately three to five minutes or until vegetables are wilted. Add smoked nutria and andouille sausage. Saute in roux approximately fifteen minutes.

Add chicken stock, one ladle at a time, stirring constantly until all is incorporated. Bring to a rolling boil, reduce to simmer.

Cook until smoked nutria is tender, adding additional stock to retain volume of liquid. Once tender, approximately one hour, add green onions and parsley. Season to taste using salt and pepper. Cook additional five minutes and serve over cooked rice.

To see a video on cooking Coypu/Nutria, click here.

Coypu in Europe

Austria:Nutria have been bred in Austria (Laurie, 1946). The capture of free-living nutria began in 1935 (Aliev, 1967)

Belgium: Nutria have been bred in captivity since the 1930s and are now feral (Laurie, 1946; Aliev, 1967; Litjens, 1980). Nutria occur west of the Maas River near the city of Limburg (Litjens, 1980).

Bulgaria: Aliev (1967) did not report nutria here. Mitchell-Jones and others (1999) reported nutria along the borders with Greece and Romania.

Former Republic of Czechoslovakia (Czech Republic and Slovakia): According to Kinler and others (1987) and Aliev (1967), nutria have been raised in captivity.

Denmark: Stubbe (1989) reported nutria were observed in the wild in Denmark in the 1930s and 1940s but could not survive subsequent harsh winters. Currently, no nutria are reported in Denmark (Mitchell-Jones and others, 1999).

England: The first nutria were imported into Great Britain in 1929 for fur farms (Laurie, 1946). A 10-year eradication campaign was started in 1981 that employed 24 trappers (Gosling and Baker, 1987). On January 10, 1989 no nutria had been trapped in 21 months and the trapping campaign was declared a success and terminated (Gosling and Baker, 1989).

Finland: Aliev’s (1967) range map indicated wild nutria populations in Finland. In the early 1990s nutria were reported escaped from fur farms, and wild populations existed in the south of Finland near Turku (K. Jutila, oral communication.). Nutria were even listed as a game species by a hunting organization (Finnish Hunters’ Central Organization, 2000). However, Mitchell-Jones (1999) classifies them as extinct in the wild. It is hypothesized that harsh winters caused them to die out in the area (K. Jutila, oral communication.).

France: Introduced into France as early as 1882, fur farming began in earnest from 1925 to 1928 (Bourdelle, 1939). Some nutria escaped captivity and became feral (Bourdelle, 1939). From 1974 to 1985 they increased in number and have been controlled with anti-coagulant poisoning (Abbas, 1991).

Germany: Nutria were first introduced into Germany in 1926, and by 1935 small wild colonies began to appear in the Elbe-Trave Canal (Van Den Brink, 1968; Stubbe, 1992; Gebhardt, 1996).

Greece: Nutria have been raised in captivity in Greece (Aliev, 1967). Between 1948 and 1966 they were observed in the wild in a variety of habitats such as ponds, lakes, ditches, rivers, swamps, marshes, meadows, and wooded areas (Ehrlich, 1967).

Hungary: Nutria have been farmed in Hungary (Sztojkov and others, 1982; Kinler and others, 1987; Salyi and others, 1988). However, Mitchell-Jones and others (1999) list them as present in southern Hungary on the border.

Ireland: Aliev’s (1967) range map showed their presence here, but he provided no further information. Mitchell-Jones and others (1999) reported them as not being present.

Italy: First imported into Italy in 1928 for commercial use (Cocchi and Riga, 1999). Nutria were first reported in the wild in 1960 (Reggiani and others, 1993). Nutria have spread from Italy to Sicily and Sardinia and are presently regarded as a pest species because of the damage they cause to rice farms (Cocchi and Riga, 1999). Piero Genovese (written communication, 2003) calculated that between 1996 and 2000, nutria caused 14 million euros in damage, and losses from nutria are projected to rise 9-12 million euros/year.

Netherlands: Nutria were introduced into the Netherlands around 1930 for fur farming, and by 1940 were observed in the wild (Litjens, 1980). Because they damage levees and the sugar beet crop they are considered a candidate for eradication by European agencies (Litjens, 1980). Control is by trapping (Litjens, 1984). Despite population losses from trapping and harsh winters nutria persist in the Neatherlands because thermal pollution in rivers allow some to survive harsh winters and immigration from Belgium and Germany replenishes the population (Litjens, 1980).

Norway: Captive breeding has been practiced in Norway (Aliev, 1967; Laurie, 1946; Van Den Brink, 1968). However, Mitchell-Jones and others (1999) list them as extinct in the wild.

Poland: Bred in captivity but also managed in a semi-wild state on ponds in Poland (Ehrlich, 1962; Kinler and others, 1987). Observed in the wild there since 1948 (Ehrlich, 1967). In a semi-captive system ponds are drained in the winter to protect the nutria from freezing in the ice (Ehrlich, 1962).

Romania: Aliev’s (1967) review did not indicate the animals were present in Romania. In Stubbe’s (1989) review of nutria in Germany, he noted they had been observed in the wild. They are now on the southern border with Bulgaria and along the Black Sea (Mitchell-Jones and others, 1999).

Spain: Nutria were captive bred in Spain (Aliev, 1967). In 1999, (Mitchell-Jones and others) they were listed as extinct in the wild in Spain. However, recent correspondence (Piero Genovesi, written communication, 2003) indicates that small populations of nutria have become established in northern Spain along the border with France, where they apparently migrated from.

Sweden: A range map indicated their presence in the wild in 1967 (Aliev 1967), and they continue to be raised on farms. However, Mitchell-Jones and others (1999) list them as extinct in the wild.

Switzerland: Mitchell-Jones and others (1999) reported coypus within Switzerland, although Aliev (1967) did not.

Former Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia – Herz., Macedonia, Croatia, and Slovenia): Nutria were raised in captivity in Yugoslavia (Aliev, 1967). Their current status is unknown.