Gar fish eggs are toxic to mammals, but the rest is edible

Eating Gar, a Taste of the Primitive

There are two things you need to know about the Gar. The first is that it is very edible, really. The second is that its eggs are toxic to mammals and birds. I could end the article right there but there’s a lot more to say about the Gar.

This is a primitive, well-armored beast, well-designed to eat anything that does not eat it. There are four species of Gar in the genus Lepisosteur. There’s the short nose gar, the long nose gar, the spotted gar, and Florida gar. Three other edible Gars are now in a different genus Atractosteus, the alligator gar, the cuban gar, and the tropical gar. They all put up a great fight when caught and can grow to several hundred pounds. They can be taken by bow, net and hook, though local laws vary. Let’s say you have caught a two foot gar. Now what?

There are two fish that are very easy to cook. One is the Pompano. It has no scales, has only large bones, a very small pocket to clean, and it’s frying-pan flat. Pompano was designed to be eaten. The next most easy fish to cook is the gar. How, you may ask, is that armor-plated beast easy to cook? Simple. You do virtually nothing to it except cook it whole. Yep, you don’t even clean it. Prop it upright next to a fire, or in your oven, and cook away. When it’s done let it cool just a little then pull the scales off, and eat the backstrap meat under the scales. Do not eat any eggs or the meat around any eggs. Read eat high off the hog, ah, fish. It’s the mesolithic way.

If that does not appeal to you, then what? Well, you can cut the head and tail off, gut the fish, and then put it whole on the grill or by a fire. Again, to get at the backstrap meat, pull a cooked scale off and dig in. If you have an ax you can also just cut the whole fish in to vertical steaks then clean the skin and entrails off and away from each semi-circle steak.

If you are inclined to clean the gar and get filets you tackle it from the top down, not the bottom up. You do, however, need the right tools. Usually tin snips, a filet knife and a hatchet. You are going to cut the back of the gar so it opens up like the cargo bay doors of the space shuttle.

First wrap a rag around the fish’s bill. It makes a handy grip. Next don’t for get the scales are sharp enough to cut you. You start by making a hole behind the head. Then put the tin snips in the hole and cut down both sides of the head. You don’t have to cut all the way around the fish, just two vertical cuts down to the cutting board. Then you cut with the tin snips straight back to the tail, and again, two vertical cuts.

Now using your fingers or a knife, or pliers, peel the hide away from the meat. Once you have the skin peeled back take your knife and slice along the back bone and ribs, away from the backbone, creating two long filets. Gray meat near the loin is stronger flavored and you might want to feed that to the cat. Some Cajuns like to make a horizontal cut at the tail then work the machete towards the head cutting off a strap of skin and scales, then fillet the backstrap off that side of the fish. If you want the cook the entire fish, you can continue to cut around the ribs and remove the entrails quite easily whole. Again, don’t eat the eggs.

Gar flesh is not flaky like most fish, nor is it fishy flavored either. It has the texture of chicken but does not taste like chicken. In fact, is closer in taste to alligator than chicken. Older gar flesh can be soaked overnight in salted water to moderate any strong flavor. You can fry the fillet, or boil them as mentioned below, or put the meat through a grinder twice and make patties out of them, spiced as you prefer. Eat hot.

A lot of people will tell you the gar is a trash fish but that is a product of grocery stores. Before stores had ice and fish markets gar was an esteem local fish for dinner. Only with refrigeration and the modern fish market with species caught thousands of miles away did the gar lose its prime place. It also lost favor as sport fishing came into being because it was too easy to catch. Now think about that, a delicious fish that is too easy to catch. Personally I have caught more gar than I ever counted. When I first moved to Florida I fished nearly every day. It was not at all unsual for me to catch at least one meal every day, and that sometimes included Gar.

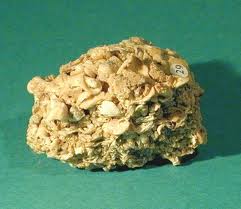

About that armor plating, called ganoid scales, which are enamel-covered bone and not overlapping. Native Americans used the scales as arrow heads. They also used the scaled skin to make protective breast plates. Even European colonists used the skin of the gar. They put it on the cutting edge of their crude plows to protect the blade.

Eggs of the saltwater Cabezon are also toxic to humans

The toxicity of the eggs has been viewed as real and as a wives tale, the latter because there isn’t much research on the issue even now. Ken Ostrand, lead author of Gar ichthyootoxin: its effects on natural predators and the toxin’s evolutionary function. Southwestern Nat., 41:375-377., 1996 has said the toxin has yet to be identified. They believe it is a protein of some kind and might be an algicide or fungicide. Apparently the eggs are not toxic to other fish which would be unusual as other fish are the most likely predators of Gar. The question is why would the toxic eggs offer no protection to the most likely predator of Gar since fishes would be the most likely predators on gar eggs (not chickens, as some studies have used, and certainly not humans). In other words, why would egg toxicity evolve if it offered no protection against the most likely predators? It may just be chance that the eggs cause sickness in birds and mammals. Or, as Ostrand suggested, converting the eggs to pellet form to feed to chickens, or even force-feeding raw eggs to mice, might involve changes in the biochemistry of the eggs which could cause an unnatural response.

Below are two toxicity reports from 2010, and they are remarkably similar in that the children got ill first and basically threw up. The adults to much longer to get ill but then lost fluids from both ends. Everyone recovered.

Cleburne County family survives bitter experience with gar eggs

HEBER SPRINGS – Not all fish eggs create caviar; some can be downright dangerous. A Cleburne County family discovered this after becoming violently ill upon eating the eggs of a long-nosed gar on April 5.

The eggs of some fish species are processed into expensive caviar, and fried fish eggs are a spicy appetizer in Indian cuisine. Even bluegill eggs can be deep-fried and served. But the eggs of all gar species are extremely toxic and should be avoided.

“My husband Darwin (Aaron) and brother-in-law Russell (Aaron) had gone spearfishing in Greers Ferry Lake and had gotten one gar,” said Tiffany Aaron. “My husband had heard that gar were good to eat, and we’ve always been a family that’s up for trying anything once.”

Mrs. Aaron said Darwin, Russell and her 10-year-old son, Carson, ate the gar and its eggs at about 8 p.m. that evening. Carson was the first to get sick, and began vomiting by 1:30 a.m. Russell became ill by 3 a.m., and Darwin followed suit at 5 a.m.

“The men were the only ones who had eaten the eggs, so I got online to find out more,” said Mrs. Aaron. “That’s when we found out they were poisonous.”

Carson was taken to Baptist Health Medical Center in Heber Springs where he was put under observation.

“My biggest question was what should we expect or watch for,” said Mrs. Aaron. “But the ER doctors didn’t have any experience with this sort of poisoning, and the Poison Control Center didn’t have any information. The one thing the doctors could tell me is that it was fortunate that my son began vomiting as quickly as he did to get the toxins out of his system.”

Lee Holt, an Arkansas Game and Fish Commission Fisheries Management Biologist conducting research on alligator gar, was contacted for more information about the type of toxin contained in gar eggs.

“I made a lot of calls to gar experts I knew from my research,” said Holt. “Our main concern was the type of toxin. There was one mention of it possibly being cyanide-based. The doctor at the emergency room explained that treatment for cyanide poisoning can be just as harsh as the toxin, so we needed to make sure before (Carson) was given any treatments.”

Holt said he found out that it was a protein-based toxin, so the harsh treatments could be avoided.

All three men recovered from the episode, but the effects of the poisoning lingered for three days.

“As it turns out, there’s so little information on the subject that researchers at Nicholls State University in Louisiana are conducting follow-up interviews about the family’s ordeal.”

A second report is undated but happened before the above news story.

“I came across this page [the above article] when I was searching for the toxin in gar eggs responsible for the severe illness my son and I encountered after consuming them. I caught and cleaned a 2′ long gar in Laplace, LA. My Filipino mother-in-law who is visiting cooked the eggs. My son had 2-4 spoonfuls mixed with rice, I had 1/2 a plate or so at about 9pm.

At about 3 a.m., I awoke to my son vomiting in the bed. We cleaned him up, and 5 min later again and again for about an hour or so followed by dry heaving. After all was “out” of him, he went to sleep.

I awoke at 7 a.m. with a slight stomach ache, ran to the bathroom, where I did not leave until 10:30 a.m., violently vomiting, severe diarrhea, sweating profusely, cold, followed by so much dry heaving I thought something would implode. At about 10;30 or so, exhausted and semi delusional, I staggered to my bed covered in sweat, laying there freezing and… the only way I can explain it… hallucinating. In my sleep until 3 p.m. that evening, I had just crazy dreams.

I awoke at 3 p.m. feeling a lot better, but still kind of “off”. Here I am the day afterward, and I still don’t feel 100%…I just feel weird, is the only way I can put it. My little boy is OK though complaining a little that his stomach felt “different”. It was one of the worst sicknesses I’ve had. I read on this post that it might be a “old wives tale”, but this needs to be put to rest. The eggs of garfish are extremely toxic and should never be consumed by anyone! I can speak from experience.”

Gar Lobster

Put some crab boil spices in water according to direction. Put in chunks or nuggets of gar (or put in cheese cloth and put in the water.) Let it boil for five minutes (or more depending on the amount of fish. You want it done.) Turn off the heat and let it sit for as long as you boiled it. Drain the meat. Dip each nugget in butter. It tastes like lobster. Another quick way is to dip the nuggets in mustard then fry. Yum.

Gar age: How to guess the age of the gar you caught by maximum length: Long nose – 22 years, 72 inches; spotted – 18 years, 44 inches; short nose – 13 years, 32 inches.) Incidentally gar may be protected in your area to check with local laws first.