Surinam Cherries: You’ll love ‘em or hate ‘em

The Surinam cherry is not a cherry nor is it exclusively from Surinam. It’s also not from Florida but it’s called the Florida Cherry because it’s naturalized throughout the state and real sweet cherries don’t grow well there.

I will freely admit these little red pumpkins are an acquired taste. Most folks are expecting some kind of cherry taste and they don’t have that. No matter how ripe, there is a resinous quality. To be blunt, you either like them or you definitely do not. More so, they must be picked when absolutely ripe or they are a very unpleasant edible experience. What is absolutely ripe? There is orange red, the color of cars, and here is blue red, the color of old-time fire trucks and blood. Surinam cherries are edible when they are a deep blood-red. Let me repeat that: A deep blood-red. An orange red one won’t harm you but you’ll wish you hadn’t eaten it. And I know you will push the envelope and try one that is not deep, blue-blood red. Don’t blame me. I warned you. You won’t die or throw up or the like but your mouth will disown you and the next time you will pick a very ripe one. The only one in the picture above that near ripe is the red one on the lower right, and perhaps the one on the lower left, and only if they drop into your hand. When fully ripe they are very sweet and juicy.

The plant is native of Surinam, Guyana, French Guiana, southern Brazil, Uruguay and Paraguay where it grows in wild thickets on the banks of the Pilcomayo River. It got to North America the hard way. Portuguese voyagers carried the seed from Brazil to India then to Italy and the rest of southern Europe and then to Florida. It is cultivated and naturalized in Argentina, Venezuela and Colombia, along the Atlantic coast of Central America; the West Indies, the Cayman Islands, Jamaica, St. Thomas, St. Croix, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, the Bahamas, Bermuda and Florida. It is grown in Hawaii, Samoa, India, Ceylon, Africa, China, Philippines, the Mediterranean coast of Africa, Israel and the European Riviera. If you’re in a warm area, that is, you don’t hit 30F too often, there is probably one near you.

It was introduced as an ornamental and edible fruit before 1931 in Florida. By 1961 it was widely planted in central and south Florida, especially for hedges. A decade later it was seen escaping cultivation and invading hammocks in south-central and south Florida. In 1982 it became a target of eradication in southern Florida. It is now reported in 20 wildlife areas as well, and threatening rare scrub habitat. Thus, by eating the fruit and destroying the seeds you are helping the environment. EAT THE WEEDS! In fact this very day I saw it along a bike trail and did by civic duty and ate as many ripe ones as I could find.

In the mediterranean area it fruits in May. In Florida, depending upon the winter, the fruit begins to ripen around St. Valentine’s day and should be available by the Ides of March and in full fruit by April Fools Day. There are two prime varieties, the common blood-red and the rarer dark-crimson to black, which is sweeter and less resinous. In Florida, the Surinam cherry is one of the most common forgotten plants and over runs many back yards. In Florida and the Bahamas, there is a spring crop and a second crop, September through November. Some times a third and fourth crop, depending on weather.

Besides being blood-red, the fruit should drop effortlessly into your hand when you touch it. If it doesn’t want to let go, let it be. Collecting should be done twice a day and often the best ones are the ones you have to fight the ants for. The “cherries” are an addition to fruit cups, salads and ice cream. They can be made pies, preserves such as jelly, jams, syrup, relish or pickles. Brazilians ferment the juice into vinegar, wine, and a liquor. The fruit is extremely high in vitamin C and A. Don’t eat the seeds. One probably wouldn’t kill you but if you think the unripe fruit tastes bad the seed is distaste on steroids. The fruit, I have been told but do not know, can be made into a fine wine.

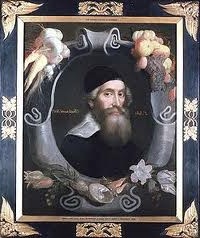

The scientific name is Eugenia uniflora (yoo-JEE-nee-uh yoo-nif-FLOR-uh.) Eugenia is named for Prince Eugene of Savoy, 1663-1736, a patron of botany and horticulture. He was a great general and spent most of his life fighting in wars, constantly. Apparently it agreed with him. When he died in his sleep at age 72 he was the richest man in the world. Yetif it wasn’t for a fruit would we ever hear of him? Uniflora is from Latin unus, one or single and folium, to bloom, read one leaf.

That said, there are in other warm areas several edible Eugenias and at least one more naturalized in Florida, but it isn’t that tasty. The other edible species include: Eugenia aggregata, Eugenia cabelludo, Eugenia dombeyi, Eugenia klotzschiana, Eugenia reinwardtiana, Eugenia Smithii, Eugenia stipitata, Eugenia uvalha, Eugenia victoriana and Eugenia axillaris, the other one found in Florida.

Surinam Cherry Chiffon Pie

by Rowena

The original recipe calls for surinam cherry juice, but this was made with some fruit pulp. Rinse the cherries and remove stems and flowery ends. Using quick pulses, process a few times then pick the seeds out. The flecks of cherry throughout the pie makes for a pretty presentation when cut and served.

1 pie crust, 9-10 inch diameter, baked and cooled

1 tablespoon unflavored gelatin powder

¼ cup cold water

4 large eggs, separated

1 cup granulated sugar

3/4 cup surinam cherry pulp (about 1½ cup fruit)

1 cup whipping cream, sweetened with powdered sugar and whipped to soft peaks

Soften the gelatin in 1/4 cup water. Beat the yolks together with HALF of the sugar and add the fruit pulp. Cook over medium heat until thick, stirring constantly. Add the softened gelatin and stir until dissolved. Cool and set aside.

Whip the egg whites until frothy then gradually add the remaining amount of sugar, beating until peaks begin to hold their shape. Fold beaten whites into cherry mixture and fill pie shell. Chill until firm. Top with prepared whipped topping just before serving. Serves 8-10.

Green Deane’s “Itemized” Plant Profile

IDENTIFICATION: Evergreen, multi-branched shrub or small tree to 30 feet, can be busy, usually shrub size in Florida; young stems often with red hairs and dark red new foliage. Leaves opposite, simple, short petiole, oval to lance shaped, Flowers white, fragrant, half in across, with many stamens; occurring solitary or in clusters. Fruit fleshy, juicy, red berry to inch and a half wide, looks like a little red pumpkin, 1-3 seeds

TIME OF YEAR: February to April, September to November in Florida.

ENVIRONMENT: Naturalized in urban areas, a border plant backyard escapee, vacant lots, untended area. In native central America range it is a thicket tree.

METHOD OF PREPARATION: Ripe berries raw or cooked. One unripe berry can taint the rest. Learn to identify the ripe ones. If you slice ripe ones open, take out the seeds, and the fruit sit in a refrigerator for a couple of hours they lost much of the resinous tang. In Brazil they ferment the juice into vinegar or wine, and sometimes a distilled liquor.

HERB BLURB

Research shows native concoctions of the tree do help in the control of Paracoccidioidomycosis (PCM), a yeasty disease endemic in Latin America, where up to 10 million may be infected. The smelly leaves can be use as an insect repellant.