Daylily: Just Cloning Around

The daylily, a standard plant in foraging for a century or more, has become too much of a good thing and now presents a significant seduction to the forager. Here is why: There are too many of them. While that would sound like a good thing, it isn’t because that has created uncertainty about edibility.

The daylily originated in Asia and has been used there for food for perhaps thousands of years. It was first mentioned in European writing in the 1500s. When the daylily was imported to North America in the 1600s there was only the unspotted orange kind, Hemerocallis fulva (hee-mer-o-KAL-is FUL-va) and it was edible, top to bottom. H. Fulva was the only daylily in North America for perhaps 200 years or more. By the 1930s breeders starting to create new daylilies. Now there are some 60,000 cultivars of daylilies. They have been bred for color, height, the number of petals, stature et cetera. The result is they are not all edible. In fact it is anyone’s guess as to whether the cultivars are edible or not. So while it is fairly easy to identify the original daylilly, and to identify a daylily cultivar, finding out if the latter is edible is a challenge. That of course, is why one needs to contact a local expert and or the owner of the daylily. While the original daylily is edible — with some qualifications I will get to — all others are to be suspect no matter what your guidebook says. If someone tells you their daylily is edible ask them to prove it. That’s what I call the “Dick Deuerling Method. Let me explain:

I spent a lot of time in the woods with a suspender-wearing, bearded forager named Dick Deuerling. He and a friend, Peggy Lantz, wrote a book called Florida’s Incredible Wild Edibles, which is still available. If someone said a plant Dick didn’t know was edible was edible, or if they

said a plant he thought wasn’t edible was edible, he’d say this to them: “Invite me over. Let me watch you harvest the plant. Let me watch you prepared the plant for cooking. Let me watch you cook the plant. Let me watch you eat the plant. Then I’ll come back the next day, if you aren’t sick or dead I might try it. “ With any daylily now, other than the original, that is what you have to do. Plants are chemical factories and within a genus there can be edible and toxic plants. The genetic selection that might produce a beautiful flower might also produce an inedible one. So seek out the original, but for all others demand proof it is edible.

H. fulva is naturalized throughout most of North American except northwest Canada and desert southwest of the United States. Surprisingly, it is not naturalized in California. (I suspect it is, it just hasn’t been reported. I know it grows in the county I live in and one to the north but the state of Florida says it is not here.) The only other daylily that has become naturalized somewhat in North American is Hemerocallis lilioasphodelus (lil-ee-oh-as-foh-DEL-us) which is the yellow version, similar in appearance and wrongly called H. Flava. The Michigan State University Department of Horticulture says H. Iilioasphodelus is edible. Blame them not me if it is not. There is one report that H. Iilioasphodelus gives half the women who eat it a bad taste in the mouth akin to sweaty armpits. No reports that it bothers men the same way. Hemerocallis minor is also reported as edible. I do not personally know that.

The original, H. Fulva, is a survivor. Actually it’s a clone. It will grow nearly anywhere there is sun and water. It often out lives the buildings it was put around. In many well-fed areas (read countries with obesity issues) it is considered an invasive weed. Since it is sterile it reproduces by underground rhizomes and thus spreads. Cultivated dayflowers stay in clumps and are not considered invasive. And as the name implies, daylilies are open for only a day.

As for edibility….. Young spring shoots and leaves under five inches taste similar to mild onions when fried in butter. They are also a mild pain killer and in large quantities are hallucinogenic. The leaves quickly become fibrous so they can only be eaten young (but you can make cordage out of the older leaves.) The flower buds, a rich source of iron, are distinguished from the plant’s non-edible fruits by their internal layering. The blossoms are edible as well, raw or cooked (as are seeds if you find any.) The dried flower contains about 9.3% protein, 25% fat, 60% carbohydrate, 0.9% ash. It is rich in vitamin A. The closed flower buds and edible pods are good raw in salads or boiled, stir-fried or steamed with other vegetables. The blossoms add sweetness to soups and vegetable dishes and can be stuffed like squash blossoms. Half and fully opened blossoms can be dipped in a light batter and fried tempura style (which by the way was a Portuguese way of cooking introduced to Japan.) Dried daylily petals are an ingredient in many Chinese and Japanese recipes (they usually use H. graminea). Nearly any time of year the nutty, crisp roots can be harvested, but they are best in the fall. They can be eaten raw or cooked. You want to harvest new, white tubers. Older brown ones are inedible.

And now for the warnings to keep the lawyers happy: While daylilies are listed in virtually every foraging book as edible as I said earlier, don’t presume any daylily other than the original is edible. Many are, but don’t assume so. Have it proven. Some people also have severe allergic reactions to them. In fact, some people can eat them for years with no problem then suddenly develop an allergy. Also, don’t go overboard with any part of the plant or you’ll be creating a lot of personal fertilizer. They are nature’s laxative. Incidentally, they are toxic to cats, including the plant’s pollen.

The flowers don’t attract butterflies or hummingbirds, however, rabbits and white-tailed deer eat tender spring leaves. Among daylily growers the original is considered old fashion and a plant below their purview. It is rarely offered by various daylily societies. The genus name, Hemerocallis, comes from two Greek words: ἡμέρα (i mera) which means “day” and καλός (kalos) “beautiful”. Fulva is Latin for tawny yellow brown. Liliosphodelus is a camelopard of Latin and Greek to mean “a lily with roots that look like they have been eaten away.” Minor means small and graminea means “grassy”

Oh, one more thing: H. fulva in 2004 research showed strong antioxidant activity. Imagine that: An invasive weed with strong antioxidant properties…. Sometimes I think botanists haven’t a clue.

Day Lily Jelly

Day lily petals, pick as many as you can early in the morning if you possible.

Water to cover.

Bring the petals and water to a boil,remove from heat. Then cover and let sit for 10 to 15 minutes. Then pour into a jelly bag or double layers of cheesecloth in a stainer. Let drip into a large bowl, until all the liquid is in the bowl; overnight if necessary.

DO NOT SQUEEZE.

Measure:-

5 cups juice

4 cups sugar

1/4 cup lemon juice

1 package pectin

Green Deane’s “Itemized” Plant Profile

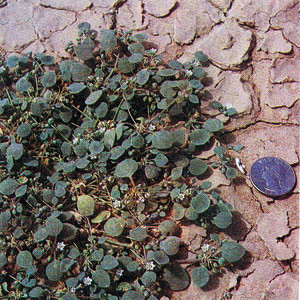

IDENTIFICATION: A rosette of basal leaves and flowering stalks three to six feet high. The leaves have parallel veins and are hairless. They taper gradually like a sword, tend to bend down from the middle and look droopy. Out of the center of the rosette are one or more flowering stalks, usually taller than the leaves. Stalks are hairless with a few green bracts. The UNSPOTTED flowers facing UPWARD are large, some three or more inches across, each with six orange tepals (three orange petals and three orange sepals similar in appearance making the flower appear to have six petals.) The inner three are broader than the outer three. The flower throat is yellow with a red band around it, the rest of the flower is some shade of orange. It also has six stamens. Buds are up to three inches long. If seed capsules are produce, they are three celled and have rows of black seeds. The roots, tuberous and yellow, are fleshy rhizomes that grow fibrous.

TIME OF YEAR: Blooms occur in April or May in the South, June and July in northern climates. Blooming lasts about a month. Each flower lasts for just a day.

ENVIRONMENT: Sunny fields, roads, empty lots, old homesteads, escaped from flower gardens.

METHOD OF PREPARATION: Flowers, buds, seed pods, and roots edible raw or cooked. Collect only young white roots. Older brown roots are not edible, poor taste, poor texture.