Gracilaria: The pot thickens

People eat a lot of seaweed. They just don’t know it. In the industry it is called covert consumption vs overt consumption. What is covert consumption?

Did you eat some ice cream recently? You ate seaweed. Some seaweeds have chemicals that control the stability of liquids. One pound of seaweed extract can stabilize a ton ice cream. Look on the label, it’s there, either as agar or carrageenan. Overt consumption is not consuming an extract but the weed itself. One seaweed genus that is used as a table food and an extract is Gracilaria, a red seaweed that’s crunchy like celery with after taste of ocean.

Found in most seas Gracilaria tikvahiae (Graceful Redweed, above) in particular is common around the water of where I now live, Florida. In fact, it is one of the major seaweeds — with G. confervoides, left — in the brackish lagoon called Indian River, about 50 miles east of here. Further, the Keys ship G. tikvahiae to Hawaii for covert and overt use. Hawaii’s Gracilaria species, G. parvispora, seems has been over harvested. The commercial use for Gracilaria is to make agar, to thicken liquid-based foods.

It’s hard to tell many of the species of Gracilaria apart, and each has its own taste and texture. Commonly used around the world are G. arcuata, G. blodgettii, G. bursa-pastorisG. cartilagineum, G. chilensis, G. chirda, G. confervoides, G. coronopifolia, G. crassa, G. Edulid, G. eucheumoides, G. foliifera, G. gracilis G. incurvata, G. lichenoides G. virinioifloia, G. parvispora, G. salicornia, G. sjostedtii, G. taenoides, G. tikvahiae, G. verrucosa, and G. vieillardii. I’m sure I’ve left off scores more.

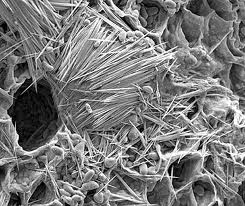

Gracilaria are bushy or irregularly branched — think red vegetable-like spaghetti with a delicious fragrance. The branches can be compressed, flattened, but are usually cylindrical. It is like cartilage when fresh, hard when dry — think coarse, dark hair. They range from light pink to purplish, some times yellowish. Gracilaria are usually found on rock and broken coral in a meter of water or so, in the littoral region, which is from the high water mark to the area of the shore permanently submerged. It can also live adrift.

As a food Gracilaria are very versatile but are traditionally used three ways. Washed and eaten as a salad, raw or boiled, as a thickener or sun-bleached, dried and used later on as a vegetable-based gelatin. Nutritionally, it is high in manganese and has nitrogen, potassium, zinc and vitamins A and B.

In Vietnam the species is collected in March and April, washed in fresh water, then kneaded into slices and dried in the sun. It is also boiled and eaten with fish, or boil, the water allowed to cool then it is sliced into cubes and sweetened with a sprinkle of sugar. It can also be washed and then pressed by hand into a gelatin-like mass that is eaten as a kind of pickle/relish or as “dabbo dabbo” which is a sauce of lemon juice and ginger.

In Sri Lanka it is made into a soup, pudding or jelly. The most popular preparation is a porridge made by washing the dried seaweed several times and cooking it in water for 15-20 minutes. The thick soup is strained, coconut cream and lime are added to taste. The commercial recipe is 4.5 pounds seaweed, three limes and 21.5 ounces sugar and 7.5 quarts of water.

In Sri Lanka G. lichenoides is eaten raw or cooked often with salt and tomatoes. That is done with fresh Gracilaria or after dipping it in boiling water. It is also served with onions and vinegar. For use later It is dried without washing. When wanted it is soaked for a day, cleaned, chopped into small pieces and eaten.

To make agar, rinse the Gracilaria in fresh water five or six time until it has lost its pink color. Then take one part washed seaweed to 50 parts water and boil gently with on or two teaspoons of white vinegar until the liquid is thick and opaque. Strain it and let it set. When cool, cut into cubes. Some like to add sugar and or fruit juice to the liquid before it jells. Another option is after it jells you can cut it into small pieces and mix with soy sauce, vinegar, garlic juice, salted vegetables, sesame oil, coriander and other spices of your choice. It it is served like a salad. A third method is to stir fry the seaweed for a minute and then simmer at least 30 minute or more with salt, soy sauce, sugar, wine, green onion and ginger. That is then cooled and once set, cut into pieces and served cold. Others way is to cook it was pork, fish or vegetables, stewing it all together. That can be eaten hot or jelled. Gracilaria can also be fried in tempura batter.

In Hawaii Japanese and Korean cooks wash the Gracilaria, drain, then blanch it. A Miso sauce, or vinegar, or a sugar-soy sauce is used to flavor the seaweed. Prepared that way it’s a strong “sea” flavor that may not meet well with a lot of Western pallets. In the Caribbean it is made into a seaweed drink that some men think helps their prowess in the bedroom.

Gracilaria, Ogo in Japanese, which sells for about $6 a pound raw, is a major source of agar. Agar is not digestible so it is roughage. It can be used as a poultice for swollen joints and Gracilaria whole makes a good fertilizer.

Locally, G. conferiodes and G. tikvahiae can be found in Florida waters and Indian River Lagoon. They can also be found up the east coast of the United States. There are many Garcilaria on the west coast including G. confervoides and G. sjostedtii. Always wash your fresh seaweed well. On the beach look for what looks like a sprig of red dill.

Gracilaria (grass-il-AIR-ree-uh) means slender leaved, or graceful leaved. According to the Smithsonian Marine Station at Ft. Pierce, FL., G. tikvahiae is a “highly opportunistic species common in estuaries and bays, especially where nutrient loading leads to either seasonal or year-round eutrophication (Peckol and Rivers 1995a, 1995b). Its morphology is highly variable, with colors ranging from dark green to shades of red and brown; with outer branches that can be either somewhat flattened or cylindrical in shape (Littler and Littler 1989). It can be found in protected, quiescent bays, as well as in high energy coastline habitats. This species grows free or attached to rocks or other substrata, and can reach a height of 30 cm (Littler and Littler 1989). G. tikvahiae grows to depths of approximately 10 m, but is most common at depths less than 1 m.”

Gracilaria-Cucumber Salad

1 pound Gracilaria, thoroughly washed and cleaned

2 medium cucumbers, peeled and thinly sliced

Rock salt

1 sweet onion, sliced in thin rings

1/4 cup cider vinegar

1 pint sour cream

1 tablespoon soy sauce

Salt and pepper to taste

Cut seaweed into 6-inch sections. Make a solution of saltwater with the rock salt and water and soak the seaweed, cucumber and onion. After wilted, drain and rinse well. Make solution of other ingredients and pour over wilted vegetables. Serve chilled.

Gracilaria Spaghetti and Tomato Sauce

1 tablespoon oil (olive)

½ pound ground beef

1 medium onion, chopped

1 clove minced garlic

1/8 cayenne

1 can tomato sauce (8 ounce)

1 cup carrot

2 cups Gracilaria

2 quarts boiling water

½ cup cheese, grated (optional)

Brown meat in oil with onion and garlic. Add tomato sauce, cayenne, carrot and herbs and simmer 15 minutes. Drop Gracilaria into the boiling water for just 15 seconds. Drain, serve with sauce and top with grated cheese. (From Sea Vegetables by Evelyn McConnaughey.)

Gaucomole Sandwich Spead or Dip

1 avocado, mashed (about ½ a cup)

1 tomato, diced (about ½ a cup)

1 cup fresh Gracilaria, washed and chopped

Juice of half a lemon

1/8 teaspoon cayenne or piece of chilli pepper, chopped

¼ cup chopped sweet onion or green onions

¼ cup cream cheese

Blend lemon juice and mashed avocado. Add remaining ingredients and serve on tasted buns, crackers or corn chips.

Gracilaria Relish

2 cups Gracilaria

Half a tomato

Half sweet red onion

1 cucumber (optional)

1 clove garlic, grated

Marinade:

¼ cup vegetable oil

¼ cup cider vinegar

3 tablespoons soy sauce

1 tablespoon sugar

½ teaspoon salt

½ teaspoon fresh ginger, grated

pinch cayenne

Wilt the Gracilaria by steaming very briefly over boiling water. Rinse immediately under cold water. Cut into 2-3 inch sections. Cut the tomato, onion and cucumber into small pieces or strips. Add the Gracilaria and combine with the marinade. Chill. Let stand 2 hours before serving.

Ahi Poke (Yellow fin tuna)

8 ounces fresh ahi fillet, diced 3/4 inch

1/2 cup Maui onion or red onion, chopped

1/2 cup Gracilaria

2 stalks green onion, sliced

1 tsp. Sesame oil

2 tsp. Soy sauce

3/4 tsp. coarse salt

What to do

Mix all the ingredients together and refrigerate overnight. The next day, serve on a bed of greens and sprinkle with toasted sesame seeds. You can also serve this immediately after mixing.

Simple Seaweed Soup

Two ounces (56 g.) seaweed

1/4 package of Enoki mushrooms

2 inches green onion(sliced length wise into strips)

2 cups Chicken broth

1/4 tsp. salt

Dash of pepper

1 tsp. soy sauce

1. Cut seaweed into bite size pieces. Wash Enoki mushrooms, cut off and discard root. Cut mushroom across into half.

- 2.Add pepper, soy sauce, salt (if needed), mushroom, seaweed to chicken broth. In small pot, heat to boiling. Garnish with green onion and serve.

Guacamole Sandwich Spread or Dip

One avocado, mashed

One tomato, diced

1/2 cup Gracilaria chopped

Juice of half a lemon or lime

1/8 teaspoon cayenne or a piece of chili pepper, chopped

1/4 cup chopped onions or scallions

1/4 cup cream cheese or jack cheese pieces

Blend lemon juice and avocado, add other ingredients. Serve on wraps, buns, crackers or chips.

Gracilaria Salad

Two cups Gracilaria, raw or briefly steamed and cooled.

1/2 pound cottage cheese

Four radishes, grated

Two tomatoes, sliced

1/2 cup scallions, chopped

Arrange Gracilaria on the bottom of a serving plate. Mix cottage cheese and grated radishes together and place in middle. Sprinkle with chopped scallions. Arrange tomato slices around the outside. Serve with yogurt dressing.

Gracilaria Kim Chee (takes several days)

Two pounds of fresh Gracilaria chopped into two or three inch pieces (about two quarts)

1/2 cup salt

2 cloves of garlic

1 bunch of scallions, or a chopped onion

Two small chillies

One teaspoon of grated fresh ginger root.

Wash and clean Gracilaria. Place in glass bowl or the like, sprinkle with salt and mix well. Weight down with heavy plate and let stand overnight. Rise well, add other ingredients, mixm pack tightly into jars and keep cool. ALlow to ferment two days until tart and red in color. Refrigerate. Let stand a few days before using.

Spicy Party Dip

Finely chop one cup of Gracilaria kim chee (above.) Add cheese and mayonnaise. Let sit for a few hours at room temperature. Keeps will in refrigerator.

Sunomono (Vinegar Salad)

One cup fresh Gracilaria

Boiling water

Clean and wash the Gracilaria. Blanch by putting in colander and pouring boiling water over it (which will turn it green.) Chill and serve with one of the follow dressings: 1) 1/2 cup vinegar with a tablespoon of honey and salt to taste. 2) One quarter cup lemon or lime juice, two tablespoons honey and salt to taste. 3) One quarter cup vinegar, one teaspoon soy sauce, one tablespoon honey, salt to taste. 4) One quarter cup miso, two tablespoon rice or cider vinegar, two tablespoon honey, salt to taste.