Ziziphus zizyphys: The Misspelled Jujube

If you don’t find the Jujube tree, it will find you. The Jujube is covered with long, sharp thorns. They hunt you down. They daw blood. They hurt. If I get within a yard of a Jujube Tree I somehow get skewered. Badly. Continuously. Inevitably.

Another little fact you are never told about the tree is if you plant it then move it the old roots, and the new roots where you plant it, will send up young shoots annually seemingly forever. You end up with a multitude of shin-high saplings puncturing your ankles. The Jujube is a pain but its fruit is tasty and versatile.

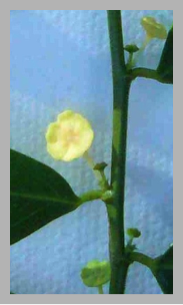

In the Buckthorn Family, the Jujube is distributed in warm-temperate and subtropical regions around the word. In the US it is naturalized in southern states from Georgia to California, excepting Louisiana and New Mexico but including Utah. Throughout the genus the leaves are quite regular and distinct. They alternate, are finely toothed, and have three prominent basal veins (coming from where the leaf meets the stem.) They also usually have two spines at the base of the leaf. The small flowers are chartreuse (yellow-green) with five petals. The fruit is a drupe, edible, that can range from green when unripe to yellow to brown to red or black. When green it tastes like and apple and has the texture of an apple. When ripe it is closer to a date in flavor and texture. A single stone contains two black seeds which are not eaten.

The Jujube has been cultivated for over 4,000 years and there are some 400 cultivars, that is, specifically bred varieties. Native to China — it’s been called the Chinese date and Indian date — Jujubes got to southern Europe around the time of the Romans and to the United States in 1837. Starting in 1908 high-quality cultivars were also introduced, initially in Tifton, Georgia by the USDA.

The genus has an interesting naming history. It was originally Rhammus zizyphys. But 15 years later it was put into a new genus but misspelled as Ziziphus. Naming rules prohibit calling the genus and the species by the same name. But since one was misspelled the name uniquely stands as Ziziphus zizyphus. There are many species including Ziziphus jujuba, where the common name comes from. It is said ZIZ-ih-fuss jew-JEW-buh (or SIZE-eh-fus.)

Ziziphus comes from two different words. Zizafun was the Persian word for the Z. lotus tree (Jujube.) Phus is latinized Greek meaning “bearing.” So Ziziphus in English means Jujube bearing. Jujube can be said two ways: JEW-jewb or JUJU-bee.

While Jujubes can be eaten out of hand they’re made into a wine, are cooked, and often are de-stoned and dried. A leaf extract, Ziziphin, alters taste perceptions of sugar in humans. It makes sweet things taste not sweet. Think of it as the anti-sweet. See recipes below. There are also numerous medicinal uses as well.

Green Deane’s “Itemized” Plant Profile

IDENTIFICATION: A small, deciduous tree to 40 feet usually with single trunk and rounded crown. Waxy leaves are simple and alternate, green on top, whitish green on bottom, in two rows on zigzaging twigs. They have hairy stems, very fine teeth, and three prominent veins. The brown bark has vertical fissures. And while I say the tree has thorns they are rightly spiny stipules. Bottom line: At each leaf you will find a half inch to one inch long very sharp thorn. Beware!

TIME OF YEAR: Fruits late in to winter depending upon climate. The fruit do not all ripen at the same time.

ENVIRONMENT: Likes sunny locations and sandy soil. Like regular watering but is drought tolerant, hardy down to -25F but needs around 200 chill hours to fruit if planted in a warm climate. It does not like to grow in a container.

METHOD OF PREPARATION: Fruits are eaten raw, candied, made into drinks, and dried. They can eaten unripe, ripe and can be left to dry on the tree. The ripe fruit is very high in vitamin C.

Jujube Cake

1 cup sugar

1/2 cup butter

2 cups dried, minced jujube

1 cup water

Bring these to a boil then set aside to cool

2 cups wheat flour

1 teaspoon soda

1/2 teaspoon salt

Sift these together then add to the above mixture. Bake at 325° F

Candied Jujubes

Wash about three pounds dried jujubes; drain and prick each several times with a fork. In a kettle bring to a boil 5 cups water, 5-1/2 cups sugar, and 1 tablespoon corn starch. Add the jujubes and simmer, uncovered, stirring occasionally, for 30 minutes. Cool, cover, and chill overnight. The next day bring syrup and jujubes to a boil and simmer, uncovered, 30 minutes. With a slotted spoon lift jujubes from syrup and place slightly apart on rimmed pans. Dry in oven, or in sun for about 2 to 3 days. Check fruit frequently and turn fruit occasionally until the jujubes are like dry dates.

Jujube Syrup

Boil syrup remaining from the Candied Jujubes, uncovered, until reduced to about 2 cups. Use over pancakes and waffles. Store in the refrigerator. Other uses: Substitute the dried jujube wherever recipes call for raisins or dates.