Ceanothus americanus: Revolutionary Tea

New Jersey Tea wasn’t always called that. It was Red Root Tea until the Boston Tea Party. With no tea from China via England colonists turned to other sources of “tea.” Two natives became substitutes, a particular goldenrod and Red Root. Since Red Root was abundant in New Jersey the name stuck.

While thought of as a northern plant New Jersey Tea (Ceanothus americanus, see-ah-NO-thuss ah-mer-ih-KAY-nus) ranges from Quebec down to Central Florida west to Texas and north to Minnesota, essentially the eastern half of North America. While the colonists used it for tea the native had many medicinal uses for it. In fact, research recently showed the roots have a blood-clotting agent. And yes, the root is red.

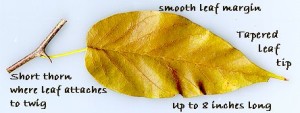

C. americanus is a shrubby Buckthorn perennial to a yard high with many branches. A native to North America, its stems are light green with a fine covering of white hairs. Twigs reddish-brown. It leaves are lance shaped, twice as long as wide with three prominent veins going from the stem end to the tip, like ribs. The flower cluster is somewhat cone shaped, elongated and rounded. Each flower has a long slender tube terminating in five folded calyxes which open into five hatchet-shaped petals with slender bases that spread outward. A large white pistil and five stamens with dark gray anthers is in the center of the flower. These flowers are pleasantly fragrance. Blooming lasts about a month in early summer in northern climes, sooner in Florida. Leaves are gathered when the plant is in full boom. Dry them throughly in the shade and then used like oriental tea, tastes similar to Bohea Tea. It does not have caffeine. The berries are NOT edible, per se.

As far as fauna, insects know a good thing when the see it. Among the wasps, C. americanus is visited by Mud Daubers, Beetle Wasps, Sand Wasps, Spider Wasps, and Crabronine wasps. Fly diners include Syrphid flies, Thick-Headed flies, Tachinid flies, Blow flies, and Muscid flies. Caterpillars of the Spring/Summer Azure butter and the skipper Mottled Duskywing feed on the foliage. The caterpillars of some moths also feed on it including the Sulfur Moth, the Red-Fronted Emerald and the Broad-Lined Erastria. Sometimes Tumbling Flower Beetles are found on its flowers, which they eat. Mammals visitors include deer, elk, rabbits and livestock.

Ceanothus is from a Greek name for a corn thistle, keanothos. Americanus means “of America.” Other common names besides Red Root are Wild Snowball, Mountain Sweet and Wild Lilac.

Ceanothus species in other areas of the country have also been used. Leaves and flowers of the C. ovatus, and the C. cuneatus for tea, the leaves of the C. sanguineus, and C. velutinus for tea. The seeds of the C. fendleri and C. intererrimus were ground into pinole by local Indians. Do NOT presume the seeds of your local Ceanothus are edible unless some one is eating them and surviving. The greater Buckthorn family sits on the cusp of edible/not edible, some of the species are edible and some are not. Four species, all in California, are endangered: C. ferrisae, hearstiorum, maritimus and masonii.

Green Deane’s “Itemized” Plant Profile

IDENTIFICATION: New Jersey tea grows to a yard tall, leaves are broadly oblong, lance to wedge-shaped, tapering to a point at the base with a blunt tip. It has a branched, racemose inflorescence with five-petaled flowers maturing from the bottom upwards. The flower petals are hatchet or dipper-shaped, all white including sepals. Loses leaves in winter.

TIME OF YEAR: Blossom in early summer, which is also the best time to pick the leaves

ENVIRONMENT: For a plant that makes tea Red Root hates to grow in water. It prefers its feet dry. You will find it in open plains and prairie like areas, sandy or rocky soils, in clearings at the edge of woods, riverbanks or lake shores, woodlands, and hillsides. meadow, old field, glades, forest; dry open woods and borders, rocky areas, openings. It prefers mountains to flatlands.

METHOD OF PREPARATION: Simple way: Hand-crush leaves slightly, shade dried the leaves, use like black tea. Colonial method: Make a decoction of leaves and twigs of the plant, dip the leaves you want to use as tea in that decoction, then let them dry. The latter was thought to ferment them slightly. Use one tablespoon of fresh leaves per cup, one teaspoon of dried leaves per cup.

HERB BLURB

From Plants For A Future Data Base: The roots and root bark of Ceanothus americanus was used extensively by the North American Indians to treat fevers and problems of the mucous membranes such as catarrh and sore throats. Current day usage of the roots concentrates on their astringent, expectorant and antispasmodic actions and they are employed in the treatment of complaints such as asthma, bronchitis and coughs. The roots and root-bark are antispasmodic, antisyphilitic, strongly astringent (they contain 8% tannin), expectorant, haemostatic and sedative. They have a stimulatory effect on the lymphatic system, while an alkaloid in the roots is mildly hypotensive. The plant is used internally in the treatment of bronchial complaints including asthma and whooping cough, dysentery, sore throats, tonsillitis, hemorrhoids etc. A decoction of the bark is used as a skin wash for cancer and venereal sores. The powdered bark has been used to dust the sores. The roots are unearthed and partially harvested in the autumn or spring when their red color is at its deepest. They are dried for later use. Other Uses: A green dye is obtained from the flowers. A cinnamon-coloured dye is obtained from the whole plant. A red dye is obtained from the root. The flowers are rich in saponins, when crushed and mixed with water they produce an excellent lather which is an effective and gentle soap. They can be used as a body wash (simply rub the wet blossoms over the body) or to clean clothes. The flowers were much used by the North American Indians as a body wash, especially by the women in preparation for marriage, and they leave the skin smelling fragrantly of the flowers.