Boerhavia diffusa: Catchy Edible

Some times you just can’t identify a plant. Some times you’re frustrated for a few days, other times for a few years. The Tar Vine eluded me for about 15 years.

I will admit to a short attention span, so over those years I would see this particular plant and tell myself to look into it but then I’d see something more interesting. More so, I was born with no patience and have even less now. But that’s off topic, so I’ll get back on track with a short story.

Way back in the mid-90s I knew an unusual fellow named Jose Gotts. I was a member of the local Native Plant Society at the time and went on many excursions with them. Gotts was one of their reigning individuals.

Picture, if you will, an aging roundish man, short, with an Algerian accent and horn-rimmed glasses, rummaging through the woods in Central Florida wearing only shorts. No shoes, no hat, no shirt. That was Dr. Gotts. Yes, doctor. He had a PhD and more in physics but was a botany professor. I never sorted that mystery out. I once asked him about the Boerhavia, though I didn’t know what it was at the time. He told me he had been trying to figure out what that plant was for a long time. He called it Soldier Weed because, he said, it was found everywhere soldiers were. He didn’t know, and I didn’t know, so it was an easy plant to ignore for another day. More than a dozen years later it was brought to my attention by our next Euell Gibbons, Marabou Thomas, a young man on the fast track to greatness. You read that here first.

The problem with Boerhavia diffusa is that locally it rarely grows in wholesome places. One usually sees it eeking out a solar living in sidewalk cracks, or a gnarly rubble pile with trash and garbage. The Boerhavia diffusa is known by the company it keeps. For a plant found on the wrong side of the tracks, it has good side of the track nutrition.

According to a 2008 study championing underused wild edibles it contains saponins, alkaloids and flavonoids. It’s 82.22% moisture, 10.56% carbohydrates, has 44.80 mgs of vitamin C per 100g dry, 97 mg of vitamin B3 and 22 mg of vitamin B2. The mineral content per 100 grams is sodium 162.50 mg, calcium 174.09 mg, magnesium 8.68 mg and Iodine 0.002 mg. Leaf extracts suggests it has possible anti-oxidant activity. It is also medicinal. See the herb blurb below.

And now comes the botanical hanky panky. Whether the Boerhavia is one or two or 40 species is a bit of debate. Some say there are two species, diffusa and erecta, others say no, just one species with variations, others say 16 or even 40. From our point of view the tempest is irrelevant but its other names include: Boerhavia repens var. diffusa (L.) Hook. f., Boerhavia procumbens Banks ex Roxb., Boerhavia repanda Wall., Boerhavia adscendens Willd., Boerhavia paniculata Rich., Boerhavia chinensis (L.) Asch. & Schweinf., and Boerhavia coccinea Mill. When botanists get important they like to change the names of plants, arguing their descriptor is more accurate. All those names translates into, respectfully, the Loosely Spreading Boerhavia, the Upright Boerhavia, the Creeping Boerhavia, the Trailing But Not Rooting Boerhavia, the Boerhavia with leaves with wavy edges, the Ascending Boerhavia, the Boerhavia with flowers in panicles, the Chinese Boerhavia, and the Red Boerhavia. All of them accurate but I don’t seen an outstanding one among them.

As for edibility the young shoots and leaves can be boiled, or made into a sauce. The root is bland, sometimes woody, but it can be roasted. Australian Aborigines ate the root raw but it can make your blood pressure rise and increase urination. The root is carrot like, some think tasting like parsnip, others say it is bland. You remove the tough outer skin before eating. The seeds can be cooked and ground into a powder to be added to other cereals when baking et cetera. The plant itself has good food for cattle and rabbits and has been used to feed pigs in the United States.

In Australia the plant is also home to a caterpillar, Celerio lineata livornicoides, the Tar Vine Caterpillar, called by the Aborigines ayepe-arenye. It’s green with a black line down its back and a spike on the end. The Aborigines would squeeze out the caterpillar’s visera, cook it, then leave it on a rock for a few days before eating it. I note that apparently nothing found it worth stealing in those few days. They also ate new cicadas raw or cooked.

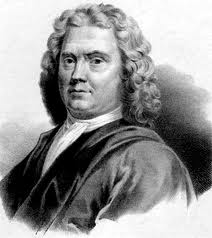

The B. diffusa is called Tar Vine because it can stick to you and other things. In fact, the Aborigines would use it like a net to capture small birds and the like. Its Latin name (for the moment) is Boerhavia diffusa, boar-HAH-vee-ah die-FEW-sa. The species, diffusa, means loosely spreading. The genus was named for Hermann Boerhaave, a polymath of great reputation in his day.

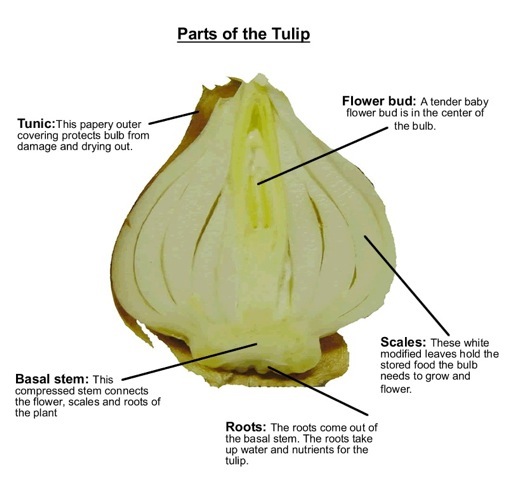

Boerhaave was a professor, physician, botanist, chemist, philosopher, reluctant clergyman, humanist, and math teacher who lived from 1668 to 1738. He was friends with the great Linnaeus and Voltaire and was a defender of Spinosa. Dutch himself, he knew German, English, Arabic, Hebrew and lectured in Latin. He also started the method of medical learning we now call interning. He was in his day the most famous physician in Europe. In fact one letter mailed to him from China got to him addressed only with: “The Illustrious Boerhaave, physician in Europe.” His home can still be seen. It is Oud Poelgeest Castle now its a hotel but a tulip tree he planted still lives. He was also a sufferer of gout, lumbago, and very allergic to bees. An attack of said when he was a kid left him with an open wound on this thigh for five years. On his death it was rumored that he left a book containing all the secrets of medicine. When it was opened all the pages were blank except one which said “keep the head cool, the feet warm and the bowels open.”

Boerhaave was a professor, physician, botanist, chemist, philosopher, reluctant clergyman, humanist, and math teacher who lived from 1668 to 1738. He was friends with the great Linnaeus and Voltaire and was a defender of Spinosa. Dutch himself, he knew German, English, Arabic, Hebrew and lectured in Latin. He also started the method of medical learning we now call interning. He was in his day the most famous physician in Europe. In fact one letter mailed to him from China got to him addressed only with: “The Illustrious Boerhaave, physician in Europe.” His home can still be seen. It is Oud Poelgeest Castle now its a hotel but a tulip tree he planted still lives. He was also a sufferer of gout, lumbago, and very allergic to bees. An attack of said when he was a kid left him with an open wound on this thigh for five years. On his death it was rumored that he left a book containing all the secrets of medicine. When it was opened all the pages were blank except one which said “keep the head cool, the feet warm and the bowels open.”

Green Deane’s “Itemized” Plant Profile

IDENTIFICATION: Perennial, occasionally an annual, sometimes the base and taproot is woody. Stems loosely spreading, ascending, or erect, usually profusely branched, hairless or barely pubescent, leaves usually on lower half of plant, larger leaves with petiole, broadly lance shaped, or oval, or broadly oval, occasionally round, or wedge shape or even heard shaped, edges wavy, tip obtuse to round, flowers terminal. purplish red to reddish pink or nearly white.

TIME OF YEAR: Year round in warmer areas, summer and fall in temperate areas. Most commonly found in Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, Mexico, West Indies, Central America, South America, Asia, Africa, Indian Ocean Islands, Pacific Islands, and Australia.

ENVIRONMENT: Disturbed areas, waste places, roadsides, dry pine lands, scrub on tropical reefs, sidewalks.

METHOD OF PREPARATION: Young shoots, leaves, boiled. Roots raw or lightly roasted. Take the skin off before eating.