Calla palustris roots can be processed into food

Calla palustris: Missen…Famine Bread

Like so many in the same family the starchy rhizome of the Calla palustris is laced with calcium oxalate crystals called raphides. These raphides are needle shaped and pierce all flesh they come in contact with, such as fingers, lips, tongue, mouth and throat. This is removed from the root by long-term drying, dry heat, or (if like the others) careful use of a microwave and drying. In Scandinavia the roots were dried, ground, boiled in water and left for several days then dried and ground again. The dry meal was mixed with other flours, including that made from the cambium of the fir tree. The roots were also dried, ground and heated until the raphides were gone. The berries can be dried and ground in to a nutritious flour but it is not at all tasty. Bread made from the roots was called “missen bread” (famine bread.)

In a book called “Vegetables Substances Used For The Food Of Man” published in 1832, the father of plant naming, Carl Linnaeus, was reported saying this about missen bread made out of the Water Arum:

Usually found in bogs

“The roots of this plant are taken up in spring before the leaves come forth, and, after being extremely well washed, are dried either in the sun or in the house. The fibrous parts are then taken away, and the remainder dried in an oven. Afterwards it is bruised in a hollow vessel or tub, made of fir wood, about three feed deep; as is also practiced occasionally with the fir bark. The dried roots are chopped in this vessel, with a kind of spade, like cabbage for making sour kale (sauerkraut) till they become as small as peas or oatmeal, when they acquire a pleasant sweetish smell; after which they are ground. The meal is boiled slowly in water, being continually kept stirring, till it grows as thick as flummery [an oat meal custard]. In this state it is left standing in the pot for three or four days and nights. Some persons let it remains but twenty-four hours; but the longer the better, for if used immediately it is bitter and acrid; both which qualities go off by keeping. It is mixed for use, either with the meal made of fir bark, or with some other kind of flour, not being usually to be had in sufficient quantity by itself…the flummery … is baked into bread, which proves as tough as rye-bread, but is perfectly sweet and white. It is really, when new, extremely well-flavored.”

Prepared berries can be edible as well

The edibility test for the dried Water Arum is the same for the Jack-in-the-Pulpit. To test them: Chew a quarter-inch square (if powder a small amount, say eight of a teaspoon) piece on one side of your mouth for a full minute then spit it out and wait ten minutes. And I mean chew for a minute and I mean wait ten minutes and I mean one side of your mouth (to limit the area that burns.) The effect can be quite delayed. If the calcium oxalate is still present it will make one side of your mouth burn, and your tongue and lips. That can last up to a half an hour or so. If no burn, try a bigger piece the same way. If no burn then, you’re ready to go. You can eat the dry chips as is, or grind them up as a flour. If you air dried them they can be used as a thickener. If you dried them at over 150F they can be used as a flour but not as a thickener because the starch will have already been cooked.

The Water Arum likes it cool and can be found in northern climates around the world. In the United States it doesn’t grow much beyond the southern end of the Great Lakes. Calla comes from the Greek word “kallos” which means good or pretty, and palustris is latin for from the bog. Lastly, I have an issue with the pronunciation. We tend to say KAL-la as in calla lilly. But Greeks would say ka-LA. So Calla palustris would be ka-LA pal-US-tris

Green Deane’s “Itemized” Plant Profile

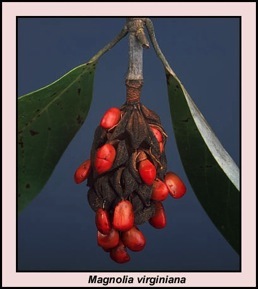

IDENTIFICATION: A hardy swamp or bog plant, in and out of the water, leaves glossy, heart-shaped, up to 6″ long, rising on 8″-12″ stems, long underwater rhizomes, to one inch through. Flower a white petal-like spathe, surrounding a yellow knob-shaped spadix. Often fertilized by snails. Fruit bright red, pear-shaped berries, covering spadix in fall. Seed brown with dark spots at one end, cylindric.

TIME OF YEAR: Best in spring before shoots are tall, or late in fall.

ENVIRONMENT: Common in along calm shores, ponds, slow moving streams, bogs, marshes, wooded swamps, and marshy shores of rivers, ponds, and lakes

METHOD OF PREPARATION: Long term drying, pounding of starch, and fiber removal, used as flour. Make sure there is no burning before consuming.