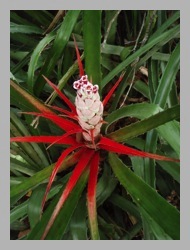

The Wild Dilly, overshadowed by a once-famous relative

Wild Dilly: Almost Chique

If the Natal Plum and the Wild Dilly could sit down and have a conversation they would probably agree that having a famous relative makes life miserable.

In the case of the Natal Plum its species sibling, the Oleander, is one of the most deadly plants in the world, the preferred plant of suicide in many parts of the world. Not exactly the best of relations to have. With the Wild Dilly the problem is nearly the opposite. It’s relative was once one of the most consumed plants in the world, or at least part of it. With a relative like that you’re always in its shadow, in this case figuratively and literally.

The Wild Dilly is the runt relative of the Manilkara zapota, the source of the original chewing gum. The Wild Dilly, however, happens to be Manilkara bahamensis and rated inferior to its relative. But from a foraging point of view, it still is of value.

The Wild Dilly is no longer used used to make chewing gum like its relative but it does have edible fruit. The only precaution is the fruit is laced with latex and is not edible until all the latex is gone via ripening, unlike the natal plumb which can be eaten with flakes of latex in it. If you pick the fruit of the Wild Dilly and let it set it will ripen. The fruit tastes a little like a pear and a lot like brown sugar. Don’t eat a lot at one sitting or it can cause constipation, unless of course you need that. Tea from the leaves have been used to treat the flu and and fever. In Cuba the tree is known as an astringent and antiseptic.

Botanically the Wild Dilly has been on a long nomenclature journey. It has been called Mimusops emarginata, Achras emarginata and Achras jaimiqui. Manilkara bahamensis (said man-il-KAR-uh ba-ha-MEN-sis) means “Malabar Bahama.” Manilkara is Latinized form of a venacular name for a similar tree in Malabar though it is a Bahama native. Achras, said AK-rass, is Greek for a wild pear tree. Emarginata (e-mar-jin-NAY-tuh) means with a notched margin (leaf end) and mimusops, (mim-MOHS-ops) is from the Greek words mimo (ape) and ops (resembling) read it looks like a monkey, referring to the fruit. Jaimiqui is the native Taino name, meaning “Water Crab Spirit.” The Wild Dilly is salt tolerant but exactly why the Taino called it the “water crab spirit” is unknown. But if I might hazard a guess: The salt water crab has angled if not distorted legs. The Wild Dilly is gnarly and grows at odd angles. Perhaps there is a connection there. (Land crabs, Hermit Crabs, are quite different.)

So your choices are “Malabar Bahama” “Notched-Leaf Wild Pear,” “Notched-Leaf Looks Like a Monkey” or “Wild Pear Water Crab Spirit.” Officially, for the time being however, it is Manilkara jaimiqui subspecies emarginata: Malabar Water Crab Spirt with Notched Leaf. Tasty is another word that comes to mind.

Green Deane’s “Itemized” Plant Profile

IDENTIFICATION: Shrub to small tree to 40 feet with milky sap, compact, round top, gnarled trunk, slow growing. Leaves alternate, oblong to obovate, notched or rounded at tip, two to four inches long, leathery with light waxy bloom on top, reddish brown hairs below, clustered at the ends of twigs. Flowers light yellow, six-lobed, to 3/4 inch wide, drooping clusters. Fruit round, 1.5 inches wide, brown, thick, scruffy skin, brownish flesh with milky sap until fully ripe. One to four seeds.

TIME OF YEAR: Flowers year round, fruits predominantly summer to fall

ENVIRONMENT: Hammocks, mangroves and other coastal thickets

METHOD OF PREPARATION: Fruit raw when ripe. Sap can be used to make gum.