Black cast iron pans are green because they last so long

Cast Iron Pans: Yesterday is tomorrow

Many books have been written about cast iron cookware. I will try to say a few things here perhaps not said elsewhere.

Buying

Cauldron with legs and lid for large jobs

I rarely buy new cast iron, for several reasons. First, I find most of what I want at garage sales and flea markets. Friends and hand-me-downs also count. More so, older cast iron pans are usually made of better iron. They are surprisingly lighter, have a finer grain making them smoother to start with, and heat more evenly than newer pans. Unfortunately there is now only one manufacturer of cast iron ware in the Unites States and while adequate their products are not superior. Functional would be more accurate.

Potato cake or Pan cake pan

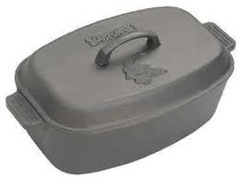

What pieces should you buy? While you can see a larger assortment below there is no argument that a very large frying pan is the kitchen workhorse. Following that is a large dutch oven with lid. You can cook nearly anything with those two and only those two pans. Other pans are nice but not necessary. And if you could only have one pan, pick the large dutch oven which can also be used as a frying pan. While I have hundreds of cast iron pans if I could take only one with me in some emergency it would be a large dutch oven. However, in modern times with an intact society I use the frying pan the most. If society fell apart it would be the dutch oven.

Square skillet

Other pans are nice to have, among them a roasting pan, grill pan, and muffin pans. Indeed, my mother who is 86 is still using the cast iron muffin pans she had when I was a kid that she got from her mother. Not only is that family history but low cost and environmentally reasonable in that you are not buying new pans every few years.

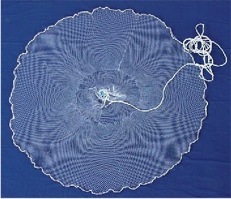

Pancake griddle

Old and New

First you want a pan that sits flat on a flat surface. No wobble. A wobble means it is warped and will heat very unevenly on a flat surface (however, if the pan is to be used only on a camp fire and is dirt cheap, the wobble can be overlooked.) Next you want a pan with as smooth a cooking surface as possible. Big pits cannot be restored and food sticks to them. (Again, if you only going to heat water in a pot, the pits are no problem. )

Swedish Aebleskive Pan

You want a pan that rings well when hit (see my video on said.) If you hear a buzz — read there’s a crack — or no resonance — thin metal — you don’t want it. You want a solid pan with some weight to it. No lightweights allowed.

Small frying pans are cute, and can be spoon rests, but I’ve never found any practical use for them nor cookie pans of different design, but then again I am a lifelong bachelor with no one to cook cookies for.

Camp oven, with legs and flat lid for coals

Unfortunately cast iron pans that used to be dirt cheap are now hot items and command very high prices. A complete Griswold dutch oven with lid and trivet can run $200. To get around that one can find them in toto or in parts at recycle centers and restore them. Complete sets command high prices but you can put sets together by piece meal if you exercise some patients. Also, anytime anyone wants to get rid of a cast iron pan speak up for it. Many people don’t understand cast iron so they don’t use it and often just give it away. Take it. It might be a collectable, can expand your collection, or, you can gift it to someone else if you don’t want it. I often pick up junked pans, clean them up, and give them away.

Griswold was bought by Wagner who also made good pans, but not as sought after as Griswold. Griswold are the collectables. Now only Lodge makes cast iron pans in the United States. While there is nothing wrong with Lodge pans I do not prefer them for several reasons. They are no doubt well-made and the value good. I do own a few. Yet they are heavy and large grain iron which I think requires more work to season. But I certainly prefer them over many foreign brands.

Two quart sauce pan with lid

When it comes to cast iron pans made in China and the like the quality can vary greatly from extremely poor to useable. Poor pans will have casting marks and often sharp edges that weren’t ground off. They often have a brown tint — not rust — to them and are often very grainy.

There is nothing wrong with a no-name cast iron pan as long as it is well made. The exterior iron will look smooth, the cooking surface will be even smoother. It will be black or gray, not brown (excluding rust.) Some Asian pans have a milled cooking surface with circular scoring. They are light weight and work reasonably well. Don’t pay a lot for them, however. On the other hand, if you are truly particular you can even custom order cast iron pans from a Canadian family-owned company.

Two handled wok

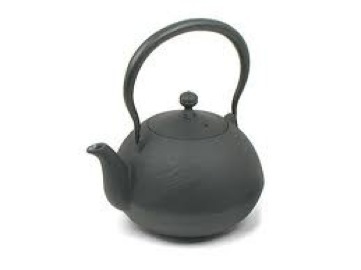

You can also buy cast iron pans from Europe that are enameled on the outside. Very expensive, chip easily. They are good pans but way over priced. The only cast iron that is enameled that you might consider are Japanese tea pots which are coated on the inside to keep down rust.

One pot not to buy – see below — is a humidifier that was made to look like a tea pot. It’s a disgusting deception. They hold a couple quarts of water and have a cheap lid on a pivot. They are very heavy, have an oversize spout, and are unmilled inside. They are not made for making hot water. They are humidifiers made of poor iron often with toxic impurities. Real cast iron tea pots are small, well designed, smooth inside, not large or bulky. These knock-offs are often sold for about $20/$30 in antique malls. If you really want a cast iron tea pot, consider several Japanese models.

Pizza pan or pancake griddle

There’s a huge array of cast iron pans, standard and custom. But there are some general things to look for.

Pans with a raised ring on the bottom were made to use on a wood or coal stove with removable lids. One would take the lid off the stove and put the pan in its place, exposing the bottom of the pan to the fire. These don’t work as well as flat bottom pans on electric stoves. Also, while pans are numbered et cetera numbers and size do not have to agree. A #8 pan can be 8.5 inches or even 10 inches.

Dutch over, no legs, rounded lid

Dutch ovens are large pots with lids and a flat bottom, made for stoves and ovens. Camp ovens, same size, have short legs to hold them above fire coals. They also have lids with rims to hold hot coals on top for even cooking, particularly of breads and the like. Older pans often have lids that double as frying pans. A lot of veteran campers don’t like camp ovens because a leg can get knocked off then you have to knock off the others and sand the stubs smooth.

Waffle pan

Numerous muffin pans were made. You will probably find many shaped like small ears of corn. Season those carefully because they are a little harder to clean than usual. Half a log muffin pans are usually older than doubles. There are also some nice french bread loaf pans from China that work well.

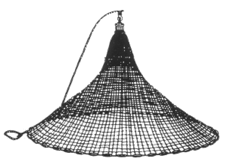

Harder to find but worth the effort I think are pans with a bail. In the winer months I do a lot of cooking with my fireplace and the bail with a wall-mounted swing arm is very handy. These pans are also useful over camp fires and the like. Many bailed pots are also rounded on the bottom for use as soup pots or stew pots.

Two sided griddle

Also look for extra handles and pouring spouts particularly on frying pans. It makes using them much easier to use, especially for women for whom heavy pans require two hands. Dutch ovens with extra handles and spouts are nice but not necessary. Conversely, do not by any pans with wooden handles. Such handles limit their use. You can’t put wooden handled pans in the oven, which is often done with cast iron. You also can’t use them over an open fire. The handles will burn off. You can use a pot holder on the handles or pick up inexpensive handle covers for the pans.

Some pans sold through regional foundries have dimples on the outside. It’s a clue to their identity and does not affect their function.

Restoring and Cleaning

Light wok

There are several ways to clean cast iron. Unfortunately too many people are just too macho about it. Before the Age of Enlightenment folks just tossed a pan into a roaring fire. That will burn off rust and crud but it can also warp the pan and damage the surface making it worthless. It is a sledge hammer approach and just not necessary.

Lye-based oven cleaners work but involves harsh chemicals. You put the pan and the cleaner in a plastic bag and set it in the sun for a few days. They are dangerous, rough on the pan, not to nice for the environment and costly. A pan is not an oven.

Two-bail Japanese Frying Pan

Soaking the pan in vinegar, or vinegar in the pan, works well but you have to watch it very closely. In a matter of hours it can etch the surface. It’s not a bad alternative but it is something you don’t do and leave. You check on it like a sick child.

Slightly dirty pans can be cleaned with coarse salt, a little oil and a plastic scrubby. One rarely needs grand abrasives. Sand blasting a pan is on par with throwing it in an inferno. Kinder, gentler works.

I prefer cleaning pans by electrolysis. It’s a simple, effective, and cheap. There’s all kinds of websites about it so I’ll just cover the basics. You put the pan in a liquid and send a low-voltage current through it. The current creates bubbles that cleans the crud off the pan and the current helps exchange ions getting rid of the rust. It costs only a few pennies a day and is totally friendly to the environment (see my video for more information.) It also can restore a pan, actually add some iron to it instead of taking it away. It can be set up in a five gallon bucket usually with stuff found round around the home. In fact, three 50 watt solar panels adding up to three amps can run your electrolysis vat. Now that’s really green.

Oven Roast

When I am done cooking with a pan I simply wipe it out. I never wash my cast iron pan basically because they don’t need it. Sometimes I will put a little water in a warm pan to help clean it but never soap. You can use soap but usually it is not needed. Once clean I coat the pan with some oil. If I am going to store a

pan for a very long time, months in a wet climate or years, I coat them with pharmacy grade mineral oil. It doesn’t hurt the pan and what is left after you wipe it off doesn’t harm us. Also, all season pans should be store with a paper towel between it and the next pan. This reduces surface damage and moisture that can promote rust.

Corn muffin pan

Perhaps no other related topic is so rife with garbage on the internet than the seasoning of cast iron pans. It is cancerous with political correctness and completely removed from practicality. I think the worst that I have read was someone selling new pans and (proudly) saying he seasoned them with flax seed oil. Flax seed oil? That is just about the most unstable polyunsaturated oil there is. It is so unstable — read easy to oxidize — one never cooks with it, ever. To subject it to high heat for seasoning can create dangerous compounds and guarantees lousy performance. It is difficult to express just how stupid that is. I’ve also read where people spray a pan with no-stick spray then throw the pan in the oven at 500F for three hours, a pointless expensive exercise that might burn the house down.

Japanese tea pot enamled inside

While I mean no disrespect to my vegetarian friends, vegetable oil is a poor class of oil to season a cast iron pan with. It gets gummy and it oxidizes leaving your pans with a rancid aroma and taste. The original is still the best, lard, also known as pig fat. My second choice would be tallow, either beef or lamb. The next question is why?

Corn bread pan

Animal fats are saturated, which means there is no place for an oxygen molecule to attach. It is oxygen that oxidizes and makes oil smell rancid. Lard is the most convenient fat to season with because it is comparatively cheap and widely available. It is easy to work with and produces superior results. If you absolutely must use a non-animal fat to season with, use coconut oil.

So with the choice of fat out of the way, what is “seasoning?” Simply put, the surface of the iron pan has minute pits in it. Seasoning is giving the surface a coating of carbon molecules which are not as sticky as untreated iron. Instead of a factory putting on a coating of non-sticky teflon (at around 600 degrees) you are putting on a non-sticky coating of carbon at moderate heat. If you look at my video you can see exactly how I do it.

Open oven pan and sauce pan

I put the pan over moderate heat outside and constantly coat it with a light sheen of lard. When the pan loses that luster, within a few seconds, I add another coat. The pan smokes constantly. But over the course of a half hour to an hour the pan gets an excellent non-stick surface. If the flame is too hot, it will burn the carbon off. If too low the fat won’t carbonize. That is why moderate heat is best. Several layers rather than a one-shot oven deal is far superior as well. It may be a small detail but it is one that directly affects the function of your pan, the life of it, and ease of cooking.

While I don’t have to here’s what I do with every pan I season. After seasoning I cook a few pounds of bacon in it over a week or two, leaving the fat in the pan. By the time I am done nothing will ever stick to the pan.

Cooking

You can cook anything in a well-seasoned cast iron pan, from eggs to fish to steak. I do add fat, oil, or non-stick spray to the pan every time I use it as I would any frying pan. The pan is not totally stick-less but rather you want the food not to stick. If you crank up the heat real high and forget to put something in the

pan your seasoning will burn off. But, if you season, use a fat or oil and cook regularly with it, the pan not only is as good as non-stick pans but it gets better with use and age. Treat it right it treats you right. This is not a use and throw away pan. It feeds your family and it needs some care.

Hook to lift lids off campfire pans

There are, however, two things you have to watch. Acidic foods, like tomatoes, can be cooked in such pans but not left in them after cooking. The same rule applies with any liquid. You can cook a soup or a stew in a seasoned cast iron pan. Just don’t leave the liquid in the pan when you’re finished. As always when done cooking, wipe the pan clean and dry.

And it is here I should add one remote concern especially if you cook a lot of acidic food. The pants do leach iron into the food you cook. For most people this is not a problem, even a health benefit. If however you have too much iron in your system or you are a man sensitive to excess iron (which can cause heart attacks) then cast iron is not the pan of choice for you. Most people know their condition already so excess iron from cast iron is not a common problem.

Humidifier, NOT for heating water to consume