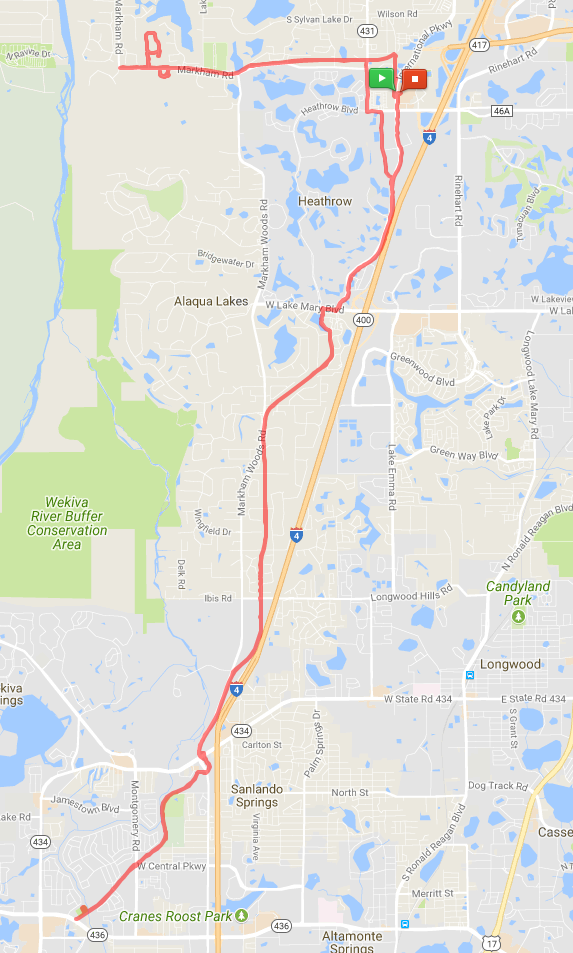

The Seminole-Wekiva Trail in 2018 (as seen from a bicycle GPS.)

Seven-Mile Appetizer

Editor’s note: Since the article was written the trail is now twice as long.

The squirrels are in hog heaven, if you’ll pardon the menagerie metaphor.

It’s Thanksgiving, 2007 in central Florida and I am starting a bike trip along a reclaimed railroad bed. The Beautyberry (Callicarpa americana) has gone from a summer wallflower to a fall blooming idiot. Also known as the French Mulberry, it is in full fruit hoping to ensure another generation of Beautyberries. The shrub, with fruit clustered along the stem, is extremely popular with squirrels, who will ignore people to get to the berries. Read more about the Beauty Berry and the great jelly it makes by clicking here.

I’m traveling from Altamonte Springs to Lake Mary, and back, a little over 15 miles. At a road crossing where I have to stop for a traffic light — an underground passage was to be finished in 2005 — I see a few scraggly Amaranth (Amaranthus hybridus.) Like its close cousin, the Spiny Amaranth, it’s a very local opportunist, rarely more than a plant or two here and there. In decades of collecting wild edibles in Florida I’ve never seen enough amaranth in one place to make a good meal (except in my garden.) Even more rare is its distant and tasty cousin, Lamb’s Quarters or Pig Weed (Chenopodium album.) It’s hard to find here in central Florida except for isolated populations usually in poorly attended orange groves.

My first introduction to “Pig Weed” as an edible came in 1960. My parents had built a house the year before and as was common the next spring they threw hay chaff on the ground to start a lawn. That summer only two kinds of plants grew on the lawn: Wild mustard — see a later article on that — and Pig Weed. A neighbor, Bill Gowen, who was also quite an amazing vegetable gardener, was visiting one day and saw the six-foot high Pig Weed and asked if he could have some. Getting a yes, he pulled out a half a dozen plants taller than himself and carried them home for supper. He was absolutely full of joy

over what he was about to eat, and with good reason. Only the Pokeweed (Phytolacca americana) comes close to Lamb’s Quarters in flavor. For many years I was fortunate in that a field near me in Maitland, Fl., grew Lamb’s Quarters profusely, though smaller than in temperate climes. But, that field is now a housing development and not one Lamb’s Quarters seed, save for my garden, seems to have survived. That cannot be said of its more malodorous cousin, Mexican Tea (Chenopodium ambrosioides, sometimes referred to as Chenopodium anthelminticum though now is has been changed by some to Teloxys ambrosiodes. In this case, the word “tea” is used to mean an infusion, not a pleasant drink. Chenopodium ambrodsiodes, by the way, means ‘Goose Foot Food of the Gods.’ That should give you some idea.

Unmistakably smelling of varnish, the cultivated version is a common spice in Mexican cooking called Epazote, which in Nahuatl, the Aztec language, means skunk sweat or skunk dirt. It is well-named. One does not need to cultivate Epazote in Florida. It grows quite happily everywhere and all along the trail I am biking, especially near Lake Mary. It is one plant I don’t stop to look at, or rub unless I want to smell like a cleaned paint brush. I might have a different view of Epazote if I had tried it cooked sometime. But, I also don’t have internal worms, another use for the “tea.” And I really don’t want to find out if the line between spice and worm killer is thin.

On my over-sized road bike I puff past many plants that are not high on the food chain for humans but edible in one fashion or another: Huge Camphor trees, relatives of the cinnamon; Pines, their needles make a Vitamin C rich tea and the inner bark edible; the aforementioned Pokeweed, red and rank this time of year but delicious in the spring when prepared correctly, deadly when not; Reindeer Moss, a true survival food; escaped Honeysuckle and Turks Caps; various cactus with edible pads and flower buds; Bull Brier, a Smilax with berries that can be chewed like gum when green. The root of its cousin made the original Sarsaparilla. Ubiquitous on the trail and very weedy, is Bidens alba.

Known as Beggars’ Ticks and “Spanish Needles” for its two-tooth seeds, Bidens is the third largest source of honey nectar in Florida. All honey from Florida is part Bidens Alba. The flowers and cooked young leaves and plants are edible. It has all kinds of medicinal applications from gout to urinary infections. Near the Bidens are some sandspurs though the correct term is sandburs, (Cenchrus echinatus.) I burn off their spines and parch them at the same time. Tasty.

About half way between Altamonte Springs and Lake Mary I pass a lawn that is too close to the trail and spy a bed of plants that would make Florida gourmets grab a shovel if they knew what was there: Florida Betony (Stachys Floridana). Its cousin, Stachys Affinis, is called Crosnes or Chinese Artichokes and a few other names. They are described as very expensive and called hard-to-find. Betony is the bane of most Florida lawns.

Also in nearby lawns as I pedal by I see two other edibles, one very esteemed and the other rarely known on this side of the world. First is purslane (Portulaca oleracea). In fact, its very name, oleracea, means cultivated and it has been for thousands of years. Invading the lawns along with the purslane is Pennywort, sometimes the native Hydocotyle bonariensis and sometimes its imported cousin, Centella asiatica, both quite edible. The Pennywort likes its feet wet and one usually finds it around lawn sprinklers or where water puddles on lawns.

This year Thanksgiving in Florida is a warm, pleasant day and I brake to read the historic markers. The trail I’m on, The Seminole Wekiva Trail, built on the former Orange Belt Railway, was at one time the longest railroad in the United States. It was started in 1885, about the same time both my grandfathers were born. In 1893 — the decade of my grandmothers —

it became the Sanford – St. Petersburg railroad then became part of the Atlantic Coast Railroad line and finally merged in 1967 into the current Seaboard Coast Line Railroad. It cut across the state higher up than the current east-west interstate then went down Florida’s west coast, with one of the stops in the Greek community of Tarpon Springs, where I got my Purslane. Many important communities along the railroad a century ago and worthy of a station are gone, only noted by the cast iron tombstones: An inn stood over there; winter visitors went to a spring-fed spar across the road; a freeze ended a citrus community here the night of 29 Dec 1894. Occasionally an area is fenced off, and on many of those fences are ripening Balsam Pears (.) They are edible when young and are one of the few wild edibles I see people picking.

As I pedal through Longwood — President Calvin Coolidge stopped here in 1929 to visit the “Senator” the largest Cypress tree in the country, now burned down — I notice the grapes are way past season save for some stragglers. The grapes were not prolific this year, but in 2006 they were abundant. There are at least three or four kinds of ‘wild’ grapes in Florida, two native and two or so escaped and semi-naturalized cultivars. It is easy to tell their ancestry: If the vine’s tendril has one tip, it is native; if the tendril is forked it’s an escape artist (although future botanists might those designations.) Along here most of the grapes are Vitis shuttleworthii and Vitis munsoniana. However, at one point overhanging the trail there are some abandoned 1930-era red and white hybrids. Larger and sweeter, they make the trip pleasant. I can just reach a last few from my bike as I go by.

Florida — as of this writing and perhaps for sometime to come — cannot grow wines like California or France because of Pierce’s Disease. The disease kills non-native grapes within a decade of planting by essentially clogging their veins and making them wither. So far its been lethal to over 300 varieties of grape. Only common varieties that have been crossed with native grapes can survive, which the state did in the early 1900s. Since the native grapes are very fruity, hybrid Florida wine, like New York State wine, is a differentiated product, a fancy way of saying it has its own muscadine flavor. If Pierce’s Disease can be conquered — they’re working on it — the South could become a major grape-growing region of well-known varietals.

3,500 year old tree destroyed by a match.

As I enjoy my grapes and pedal along I think about the “Senator.” A core ring count said it was some 3,000 years old. When it was 600 years old Socrates was arguing against democracy — why he was later executed — and Plato was a bright kid with a large derriere (didn’t you ever wonder what “Plato” means in the original Greek?) By the time the Senator celebrated its 1,500th birthday, King Arthur was becoming a legend in his own mind. I wonder how many hurricanes has that king of cypresses endured in 3,500 years, and which one blew its top off with the help of lightning now and then. (Editor’s note: An addict climbed over the security fence January 16, 2012, then lit a fire inside the trunk so she could see what drugs she wanted to use. The resulting fire burned down the tree. A clone has replaced it.)

Not far from the grapes, before a long grade that challenges my low-carb knees, grows Spotted Horsemint, also known as Spotted Beebalm (Monarda punctata.) Frankly, given its name and appearance I think they missed a linguistic opportunity. They should have called it Pinto Mint. It can be found near the trail for about two miles. It’s a plant one doesn’t notice until fall when it gets pink and white showy. Last year on private property near the old line, I dug up one small bush of it and successfully transplanted it into my small yard. It’s pretty and makes a nice tea. The bees are happy, too.

Common along the trail are Live Oaks, (Quercus virginiana) which are according heavily, if one can conjure such a verb. In the white oak family, Live Oaks have the least amount of tannin in their acorns. But, it also varies from tree to tree. One can often find a Live Oak with acorns that are edible without leeching, a convenient and time saving arrangement. Acorn meal — free of tannins or otherwise leeched of them — has many uses in the kitchen not the least in making bread.

Less common along the bike path are native Persimmons (Diospyros virginiana) which means Fruit of the Gods. They are usually small trees that like to grow on edges of fields and roads, and fortunately, old railroad beds. I counted no less than eight Persimmon trees, several with fruit. There is very little to not like about the Persimmon, which is actually a North American ebony. The fruit is edible and can be used in any way banana is used, one for one. The fruit skin can be used to make a fruit “leather.” The seeds can be roasted, ground, and used to stretch coffee. The leaves make a tea rich in vitamin C, though the taste is bland if not “green.” And the wood can be worked.

On the shy side, the native Persimmon can be small and very astringent. There are many rules of thumb about how and when they can be picked for ripeness and non-astringency. In my experience, the best persimmons are the ones you have to fight the ants for.

On my return leg I stop half way and watch a place that has, of all things for suburbia, a few milking goats (If you must know, Capra hircus.) Of Greek heritage and a farm boy, I like goats and have often fed them some grass that’s just out of reach through the fence. In fact, while feeding them one day I saw a Sassafras rootling (Sassafras albidum) looking for a new home. The transplant was successful and I am probably the only homeowner in Florida with an intentional Sassafras tree in my front yard. It makes me feel special. I also have a Zanthoxylum clava-herculis rescued more than a decade ago from a bull dozer in Daytona Beach. Should I have a tooth ache it will come in handy because its leaves have a natural novacaine. Between the Sassafras and the Hercules Club my yard has to be a rarity.

As I near where I started I cross a small brook that eventually ends up in the Atlantic at Jacksonville. A plant growing in it reminds me books can be very wrong on edibility. I know that from personal experience. Some 20 years ago I thoroughly research a particular aquatic plant here in central Florida and found several authoritative references to it being edible. While preparing it for cooking my hands began to burn severely. Only washing with Naphtha Soap stopped the burning (every forager should carry Naphtha Soap with him.)

Since this is my inaugural article* following entries will be shorter, I promise. Oh, and for Thanksgiving, I cooked a duck and had homemade elderberry wine.

* This first newsletter was written on Thanksgiving Day 2007. As of this editing — November 2018 — there have been some 1000 articles and 331 newsletters, first monthly then weekly.