I am not a survivalist per se, though every day I do break my personal best record of consecutive days alive.

I am not a survivalist per se, though every day I do break my personal best record of consecutive days alive.

That said, I know many survivalists. They tend to be men and fall into two camps, responsible older men determined to survive in what they see are difficult times ahead that they hope never comes. The other camp is young men who think along Rambo lines, a gun and a mountain top is all they need plus are few sex salves. They are anxious for society to fall apart. With the responsible group inevitably the issue of edible wild plants comes up. I have a lot of folks who say they plan to come to my place should there ever be a shortage of food. I think, however, there are some misnomers about living off the foraged land.

Often I walk 15 miles or leisurely bike 30 or so. And when I do I take note of the edible plants I see along the trip and what kind of meal or meals I could make by day’s end. Doing that inventory often makes three things apparent. One is that every single opportunity for food would have to be exploited, no matter how meager. Two, it would take most of ones time to collected and prepare the food. And, lastly, that capturing some creatures makes the entire endeavor far more nutritious.

Let’s take those backwards. Usually every time I am out walking or biking this time of year I see a tortoise. In real hard times that would be dinner, and breakfast and the next supper as well. More so, it is easy to get — pick it up — and a huge concentrations of the stuff our bodies want and need. All life lives off the living, even vegetarians (who seem to discriminate against vegetables by eating only them.) That tortoise I see every time would keep me living for another day or two. (That one, by the way, is protected.)

Let’s take those backwards. Usually every time I am out walking or biking this time of year I see a tortoise. In real hard times that would be dinner, and breakfast and the next supper as well. More so, it is easy to get — pick it up — and a huge concentrations of the stuff our bodies want and need. All life lives off the living, even vegetarians (who seem to discriminate against vegetables by eating only them.) That tortoise I see every time would keep me living for another day or two. (That one, by the way, is protected.)

Next is time. It would take a lot of time to find enough food to survive each day. Occasionally there would be a bonanza of something, like a grape harvest, but most of the time it would take a lot of time to find enough to live off. And then one has to collect fire wood, find clean water, prepare the food and cook it. There are only so many hours in a day. It is difficult for one person to do all the things that need to be done to survive let alone thrive.

Next is time. It would take a lot of time to find enough food to survive each day. Occasionally there would be a bonanza of something, like a grape harvest, but most of the time it would take a lot of time to find enough to live off. And then one has to collect fire wood, find clean water, prepare the food and cook it. There are only so many hours in a day. It is difficult for one person to do all the things that need to be done to survive let alone thrive.

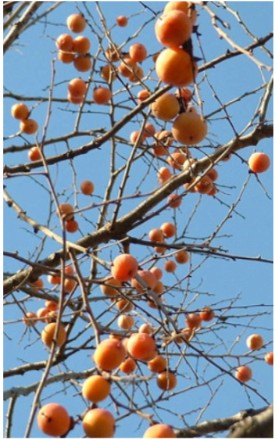

Then there is the variety, or specifically lack there of. Here in Florida I can always count on some Biden alba leaves to eat, some acorns that need leaching, cattails, lichen, spurge nettle roots, seasonal fruits, seasonal leaves, and other seasonal nuts. Sustainable, perhaps, but there are going to be lean days, weeks, months and seasons. Worse the menu is going to be the same and change only by season.

Compare that to someone who knows how to fish. One medium size fish and you won’t starve that day. While it takes some skill to fish it is not difficult to learn. (Personally, I have five cast nets and almost never come home with an empty creel.) The hunter, more controversial, gets even more food than the fisherman, but that requires far more skill, and of course, a weapon, which is much harder to come by than making a pole, line and hooks. (Though trapping can also be included in hunting, but that too takes more skill than fishing, and takes longer to learn.)

Compare that to someone who knows how to fish. One medium size fish and you won’t starve that day. While it takes some skill to fish it is not difficult to learn. (Personally, I have five cast nets and almost never come home with an empty creel.) The hunter, more controversial, gets even more food than the fisherman, but that requires far more skill, and of course, a weapon, which is much harder to come by than making a pole, line and hooks. (Though trapping can also be included in hunting, but that too takes more skill than fishing, and takes longer to learn.)

And then there is foraging, what we started out with. While foraging is near and dear to my stomach it is the skill that takes the longest to learn and produces the least amount of calories, typically 34% of a hunter/gatherer’s caloric needs. It also takes up the most time. That would all seem to argue, especially to my survival friends, that learning to fish would be a priority, hunt next and down the road foraging. In fact fishing and traping can be very efficient in that they can be done while you are doing something else that needs to be done, like setting up camp. Oddly, foraging may still have greater value than fishing or hunting in the long term.

And then there is foraging, what we started out with. While foraging is near and dear to my stomach it is the skill that takes the longest to learn and produces the least amount of calories, typically 34% of a hunter/gatherer’s caloric needs. It also takes up the most time. That would all seem to argue, especially to my survival friends, that learning to fish would be a priority, hunt next and down the road foraging. In fact fishing and traping can be very efficient in that they can be done while you are doing something else that needs to be done, like setting up camp. Oddly, foraging may still have greater value than fishing or hunting in the long term.

If we were ever in a true survival mode where we had to gather our food (by hand, hook or Colt 45) fish would be the first depleted food. Animals next. Plants last, and by that time there just might be less people around. So even to the survivalist foraging can have value, even to the Rambos. Many survivalists, who like to think they are a breed apart, share this in common with most people: They don’t know much about plants, and like many folks, just ignore them. They think all they need is a good foraging book with pictures. That mentality also extends to gardening, as in all it takes is putting the seeds in the ground. Gardening is humbling and it takes about 10 years of study to be able to produce what you want to produce when you want it.

If we were ever in a true survival mode where we had to gather our food (by hand, hook or Colt 45) fish would be the first depleted food. Animals next. Plants last, and by that time there just might be less people around. So even to the survivalist foraging can have value, even to the Rambos. Many survivalists, who like to think they are a breed apart, share this in common with most people: They don’t know much about plants, and like many folks, just ignore them. They think all they need is a good foraging book with pictures. That mentality also extends to gardening, as in all it takes is putting the seeds in the ground. Gardening is humbling and it takes about 10 years of study to be able to produce what you want to produce when you want it.

I like to forage because it makes me part of the world I am in, whether society is together or falling apart. I will forage for fun and flavor whether society is tact or not. And while I do not expect society to disintegrate, I like the idea that I can always find something to eat nearly everywhere.

Landmarks — accomplishments — are like a melody. Regardless of your taste in music, music is more than organized sound. Music firmly places you in time. When a melody starts, that is now. After a note or two you have a now and a past. And when you anticipate where the melody is going, you have a past, a present and a future. A melody fixes you in time. So do landmarks.

Landmarks — accomplishments — are like a melody. Regardless of your taste in music, music is more than organized sound. Music firmly places you in time. When a melody starts, that is now. After a note or two you have a now and a past. And when you anticipate where the melody is going, you have a past, a present and a future. A melody fixes you in time. So do landmarks. the fall of 2008 I started writing articles about wild plants on a MAC blog format, which explains some of strange ways I had things organized then. In the spring of 2009 I started making related videos and posting them on You Tube. In that first year I wrote about more than 100 plants, and made 46 videos. A year later it was close 400 plants — counting related species — and 100 videos. Now, as three full years are about to close it is over 800 plants and 133 videos. It is also some 1.2 million video views and 14,ooo subscribers. this month a new landmark was made, a new website. Nearly everything on the old site is now on the new site save for one article, which has been written but not posted yet. Unlike the original site, this new website is a team effort.

the fall of 2008 I started writing articles about wild plants on a MAC blog format, which explains some of strange ways I had things organized then. In the spring of 2009 I started making related videos and posting them on You Tube. In that first year I wrote about more than 100 plants, and made 46 videos. A year later it was close 400 plants — counting related species — and 100 videos. Now, as three full years are about to close it is over 800 plants and 133 videos. It is also some 1.2 million video views and 14,ooo subscribers. this month a new landmark was made, a new website. Nearly everything on the old site is now on the new site save for one article, which has been written but not posted yet. Unlike the original site, this new website is a team effort.