A farmer’s headache is not necessarily a forager’s delight.

Palmer Amaranth (Amaranthus Palmeri) has been a foraged food for a long time. It was used extensively by the native American population with at least seven tribes preparing it a wide variety of ways. More on that in a moment.

Amaranth, in general, is a good wild food. It occupies the middle ground between excellent and poor. When collected very young Amaranth is a dietary analogue to spinach, which is a relative. At the meristem stage, still young and tender because the cells are still growing, it’s a tasty green usually boiled. Later it becomes a source of grain. These stages, however, are dynamic, changing and they change at different rates with different species of amaranth. Some amaranths stay more palatable longer than others. More so, depending upon growing conditions, amaranth can also accumulate high levels of nitrates and oxalates making them less than desirable to eat, for you or livestock.

Palmer Amaranth doesn’t stay young and tender too long. It converts CO2 into sugars more efficiently than corn, cotton or soybean. This allows for rapid growth even when it’s hot and dry because it also produces a large taproot that is studier than that of soybeans or corn and can penetrate hard soil better than cultivated crops, read it can reach water and nutrients other plants can’t reach. Under ideal conditions, Palmer Amaranth can grow several inches per day, upper left. The species also has a rugged stem to support that growth and height.

Palmer Amaranth Pulled From A Peanut Field, photo by Rome Etheredge, extension agent, Seminole County, Georgia.

If you think Palmer Amaranth is already a Botanical Bully then consider this: It is unusual for an amaranth in that it has male and female plants which greatly aids in distribution and ability to adapt. It can also produce half a million seeds per plant. Every seed is a chance to defeat Genetically Modified Organisms, which are quite expensive to develop. When you consider Ma Nature produces million of Palmer Amaranth plants every year that adds up to perhaps billions of chances annually for her to roll a winner, virtually for free. And that’s exactly what happened. Palmer Amaranth developed a resistance to the weed killer glyphosate and became a superweed. That resistance is costing literally millions of dollar in lost agricultural crops. It “single-plantedly” ruined large farming operation in southern Georgia. That has lead to a lot of hard feelings and finger pointing.

With the help of a nescient media and the no-quality-control Internet the issue is putting farmers and foragers on opposite ends of the nasty rumor mill. More so, what is playing out in Georgia can and will happen elsewhere because resistant Palmer Amaranth is now found in some 20 states. Also, the resistance is expected to spread to other amaranth species plus other edible weeds are developing resistance which brings new meaning to the phrase “seeds of change.”

Threatening perhaps 500 acres of soybean and cotton in 2004 Palmer Amaranth by 2010 was affecting up to two million acres in the lower half of Georgia. While that put thousands out of work on the other side of the garden row were foragers saying ‘not all is lost, all you have to do is eat the weed.’ It was inevitable that Internet sites began saying experts were advising people not to eat Palmer Amaranth because the resistance, a kind of botanical doomsday scenario from a grade B movie. ‘Palmer Amaranth killed our crop and it will kill you too.’ That led to a lot of email to me and we all get too much email. I thought getting to the nitty gritty of it all would in the long term help ease my email inundation.

The person most often cited as saying the resistant amaranth is not edible is Dr. Stanley Culpepper, associate professor, University of Georgia, and Extension Agronomist. Not so. I contacted Dr. Culpepper personally regarding the edibility of Palmer Amaranth and asked him about it. His view is quite different than what’s rumored on the Internet.

“If one decides to eat Amaranthus Palmeri,” Dr. Culpepper said, “there will be no difference in its taste or nutritional value if it is resistant to glyphosate or not. To date, we have not documented any change in the biological aspects of plant growth or reproduction with regards to resistance.”

That’s quite straight forward. Where in that statement do you read Palmer Amaranth is not edible? No where. Dr. Culpepper’s post doctoral assistant, Dr. Lynn Sosnoskie, who was also kind enough to contact me, added that there shouldn’t be any difference between the resistant and non-resistant plants though that was not specifically tested by researchers. More so Dr. Sosnoskie said that unless one actually tested a plant for glyphosate one could not readily tell the difference between a resistant and a non-resistant plant. However Dr. Sosnoskie did add an observation of interest to us forager. She said Palmer Amaranth tends to grow mostly on highly managed agricultural land and that land has “likely been treated with insecticides, fungicides, and/or herbicides.” That is important.

Thus, and this is my opinion not Culpepper’s or Sosnoskie’s so blame me not them: If there is an issue with Palmer Amaranth edibility it might not be the plant or glyphosate resistance per se but that of an unmanaged plant growing on highly-treated agricultural land. Unlike a commercial crop grown on such land with supervision and exact timing a wild plant might be on such land too long, under the wrong conditions, or harvested at the wrong time. I can see how that might affect edibility particularly with amaranth’s penchant for taking up too much nitrates and oxalates. Again, that is my opinion not Culpepper’ or Sosnoskie’s.

The philosopher William James, and brother to novelist Henry James, always insisted there be a practical side to everything, including philosophical notions. A hard-core New Englander he called it “take home change.” What’s the “take home change” of all this? Palmer Amaranth is edible but not the best of the amaranths. There is no evidence the edibility of Palmer Amaranth is different if it is “resistant” or not. It’s fast growing and does not stay young and tender very long. It can accumulate elevated levels of nitrates and oxalates and would probably do so on improved land, read land that is fertilized a lot such as agricultural land is. Amaranth on unimproved land usually has safe levels of nitrates and oxalates.

The foraging advice of “just eat” Palmer Amaranth does not take into consideration the environment. As my readers know I champion my I.T.E.M. system of foraging and that includes E, for environment. In this case the edible plant in question usually grows in a highly fertilized if not chemicalized environment (vs the poor soil it usually inhabits.) This increases its chances of having higher than normal nitrate and oxalate levels, and probably other things, too. You have to take that inconsideration as part of your foraging decisions. I personally doubt some young and tender Palmer Amaranth plants are much of a problem. But, older plants could be and adult plants might sicken livestock. Also, the problem should lessen with time if the fields lie fallow. It’s an environmental issue more than a genetic engineering one for us foragers. Now you have the accurate information and reasoning you need to make an informed foraging decision regarding Palmer Amaranth in agricultural fields in Georgia. That said, what about Palmer Amaranth?

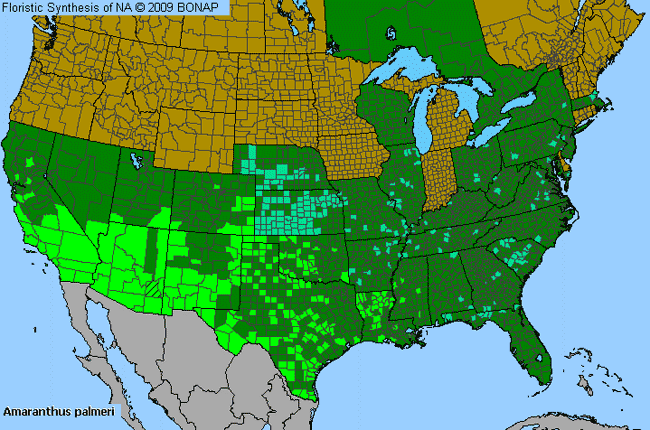

Amaranthus palmeri aka Carelessweed, is one of 60 to 70 species in the genus, depending upon who’s counting. Palmer Amaranth is a very competitive native now found in 30 states but not reported yet in Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Delaware, Michigan, Alabama, Hawaii, Indiana, and the northern tier states from Iowa north and west.

The Cocopa, Mohave, Navajo, Papago, Pima, Pima Gila River and Yuma tribes all used the Palmer Amaranth for food. Their methods varied greatly including: Fresh plants baked and eaten; leaves boiled as a green; leaves cooked, rolled into a ball, baked and stored; leaves dried then stored for winter; leaves boiled and eaten with pinole; seeds ground into a meal; parched seeds ground then chewed for sugar; seeds parched, sun dried, cooked, stored for winter.

Amaranthus (am-ah-RAN-thus) is from Greek means unfading, or evergreen. Palmeri (PALM-er-ee) was named in 1877 after Edward Palmer, plant explorer extraordinaire. Palmer was the right person in the right place at the right time. When Europeans first landed in the new world they were very interested in plants but didn’t record much about how the natives used most of their plants. By the time the white man was pushing west to California a different attitude prevailed. This is why in most ethnobotanical references we know far more about what the Western natives did with plants than the Eastern natives. And one of the reasons why we know that was Edward Palmer, 1829-1911. He collected over 100,000 specimens and discovered some 1,000 new species. Palmer also visited local markets to get plants and study how they were used helping to found modern ethnobotany.

Green Deane’s “Itemized” Plant Profile: Palmer Amaranth

IDENTIFICATION: Amaranthus palmeri: Long dense, compact terminal panicles to 1.5 feet, tall — six feet — with alternately arranged leaves, petioles longer than the leaves. The leaves of Palmer Amaranth are also without hairs and have prominent white veins on the under surface. The male flowers have highly allergenic pollen.

TIME OF YEAR: Flowers summer and fall

ENVIRONMENT: Agricultural land, disturbed areas, riparian locations, desert, uplands.

METHOD OF PREPARATIONS: Young leaves, young plants, growing tips boiled, baked or dried. Seeds used as grain, parched, roasted, or ground into flour.

fantastic post!

considered and very informative – thank you.

Brian

Agree. Thank you.

Looks like a common weed that I have pulled from my garden. I call it a pigweed, having learned from my dad.

I don’t eat any weed or its seed off of farmland, unless it’s an organic farm. However, I will gather seeds and plant them on clean soil. In the case of pigweed, it’s hard to find down here in 10a in the populated areas anyway, because they mow the road shoulders so much. I would have to go out to some undeveloped areas to find it, and it doesn’t seem too common in these parts.

Thanks very much for this helpful information! The farm I live on, where Native Americans used to live, grows pigweed – Palmer Amaranth – better than anything. Now I realize it has probably done so for hundreds of years. We also have native prairies. This land has never had much if any in the way of fertilizers or pesticides applied and has been certified organic, so this is not a highly fertilized or chemicalized environment – but Palmer Amaranth thrives and abounds. The past couple of years, we are trying to improve soil fertility and deal with an abundance of weed and insect pressure. I have often said, “If I could sell pigweed, I would be a wealthy woman.” I have despised Palmer Amaranth, but I will try to improve my attitude towards it. Maybe I will try producing amaranth flour to sell for those looking for a gluten-free flour. I will try harvesting and preparing young plants.

I have an amaranth growing next to my compost bin. Just identified using the info from this site.

Thanks

I have been thinking about this for a while, if palmer amaranth converts co2 into sugars much faster than corn, it can be used to produce sugar and ethanol, and it grows much faster and easier than corn.Why are we not using this weed to our advantage, farmers that are struggling to produce profits could make large profits if this weed was more acceptable by the main stream.And it would free up our corn crops to be used for just food.

That is just too brilliant and easy for government forces to recognize or deal with.

Good point.

I was thinking the same thing. Sounds like a better plant for ethanol production, more efficiently producing sugar while lowering water consumption and the need for herbicide.

My agronomy friend suggests it may be harder to distill the sugars out. Likely no one thought of it.

That is the best idea I have heard. If it’s edible why not nurture it, process it and sell it. Go for it!

Great article! Does this plant take-up heavy metals or PCBs?

Thanks!

I’ve not seen any research to that effect.

We bought mountain land in western Virginia. The former owner’s mother had requested – years ago – that they plant that “nice-lookin’ stuff for ground cover.” It was called Kudzu. After it spread on every possible electrical and phone line as well as up buildings, trees and the house, the former owner, to my frantic complaint and plea for a solution, said, “Well, ya just git yourelf a cow.!

Now genetically modified plants, with no defense, are being “out-eaten” by this Palmer amaranth. Well, other than the fact that it is assimilating huge amounts of minerals and salts from the soil, might we regard it as rescuing the land of these excesses from fertilizers?

Hmmm.

Excellent article.

Thank you! nancy morse

Our cows eat pigweed/Palmer amaranth. Our pastures, which tend to be acidic, have not been fertilized, other than with manure from grazing cattle and a little limestone, in fifteen years. So far, Palmer amaranth is not invasive where our cows graze, and the plant poses no danger of toxicity in this natural scenario. Our problem weeds are spiny pigweed and glyphosate-resistant marestail, which the cattle will not graze after the plants begin to mature. The cattle will eat very small plants and seedheads but not the spiny stems, which quickly produce new seedheads after being grazed or mowed. Spiny pigweed is particularly invasive during hot weather where animal manure has enriched the soil as cool season forages slow their growth or go dormant. We have read that spiny pigweed is valued as human food in Africa, Thailand, the Phillippines and the Maldives. Would love to find a good market for it!

Interesting…I wonder if the acidic soil prevents palmer amaranth from growing. Do you use glyphosate?

Just put them in the supermarket. Their a lots of Asians in this country. These are the best vegetable we can have. We love them and it’s hard to fine.

Unfortunately having been heavily sprayed with glyphosate, and/or other insecticides plus probably having toxins from having been grown amidst fertilized fields would tend to make this amaranth, in my opinion not worth eating. It may or nay not have more pesticide/herbicide residue than the crops it’s grown among.

I have a gazillion amaranth plants growing at my farm in Texas. Never use herbicides or anything like that. All organic. I can send seeds if you want. Koreans have been picking the young leaves and eating them quite a bit.

I just read an article in our local paper. It was titled Dangerous weed takes root in Ohio. I have heard alot about Kudzu but they call this Palmer amaranth weed. Is this actually Kudzu or just a similar weed? I have seen what Kudzu is doing in Tenn. I don’t like the idea of it starting here.

Kudzu and Palmer Amaranth are two very different species. More so kudzu is a vine, the amaranth is a stand up plant.

I’m behind on my mail but also read the same article in “My Own Rural Life” (of southwest Ohio) newspaper I get every month. I’m not sure who sponsors this paper but I suspect it is associated with the Farm Bureau?

Great ideas suggested so far. A bio fuel source for a native plant is the best one I’ve heard yet. The only thing that alarms me is hearing the chemical companies want to push 2-4D broad leaf killer for corn and a broad leaf ready soybean . There is the nightmare. Plants are like all the insects we’ve been fighting for years. Resistance is built in to all organisms. Will we be resistant?

Ah…. you don’t mean my article in “My Own Rural Life” but a different article on Palmer Amaranth. I note the researchers who caused the problem are not part of the solution.

in india we eat the leaves and seeds of amaranth.leaves when tender and seeds as grain like wheat etc.it is gluten free good protien etc.

why go for gmo when mother nature gives better ?

we make flat bread from it.it is tasty and nutty.tastes better than wheat.

How is it a spinach relative when spinach is a chenopod and this is the amaranthaceae genus?

They are botanically related, like people.

In Greece we treasure our Vlita, aka amaranth. The leaves, boiled with some olive oil and lemon, are heaven. My Greek friends in North American are always asking me to bring Vlita seeds to them for their gardens…I wonder if this is necessary!

Baker Creek http://www.rareseeds.com sells amaranth seeds.

I live in mexico in winter & buy a sweet grain 4 my breakfast,that is labelled amaranth.We called itbee pollen.Its supposed 2 be good 4 your health.Its good 2 know it comes from this plant…I don’t see much of this product in stores here in Canada

Wait! I am confused! Bee Pollen is a by-product of honeybees when they make honeycomb. Amaranth is a seed that is harvested ..the dietary benefits are completely different, in my own experience with the both of them. Are you simply calling the Amaranth bee pollen because it tastes sweet, or similar to bee pollen?

I say we just burn the dam weeds!

Some people do.

How much glyphosate accumulates in the leaves and seeds? That should be tested before recommending that anyone eat it from heavily glyphosate-treated fields. Humans are already ingesting glyphosate at an alarming rate.

Residual glyphosate is a concern but so to are nitrates.

Amaranth is a native plant spreading North due to climate change.

Palmer is spreading do to transportation of cotton seed from Deep South to states further north. It’s not because of climate change. Palmer is a native species that found its way into row crop agriculture. Unfortunately it was resistant to a commonly use herbicide glyphosate. Once it got into grain and cotton it got transported too many parts of the country. It’s definitely a weed that you do not want growing on your property. Some states have classified it as a invasive species.

Palmer is spreading do to b transportation of cotton seed from Deep South to states further north. It’s not because of climate change. Palmer is a native species that found its way into row crop agriculture. Unfortunately it was resistant to a commonly use herbicide glyphosate. Once it got into grain and cotton it got transported too many parts of the country. It’s definitely a weed that you do not want growing on your property. Some states have classified it as a invasive species.

Thought you folk might be interested in a new Australian invention that eradicates weed seed during harvest – chemical free too – it’s worth a look

http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-06-17/australian-farmers-invention-draws-world-interest/8619826

Great! Brilliant. Peoples creative intellect is like Amaranth seed diversity. Stated above. Hope this guys method goes global and becomes default. Larger life cannot survive induced elemental catastrophe too easily. 95% is phenomenal. Just discussing soil seed banks today, almost synergistic on this end. Blaze on bro!

I live in Moose River, Maine and I’m foraging this plant from my garden weeds.

I grew up in Pownal, Maine.

A bit of a contradiction isn’t it ??

“…the edible plant in question usually grows in a highly fertilized if not chemicalized environment (vs the poor soil it usually inhabits.)”

No. The plant does very well in soil low in nitrogen. But in fertilized soil it takes up large amounts of nitrogen.

All this mention of nitrates and oxalates seems to focus on the leaves. Is that an issue with the seed heads too? We always get loads of this amaranth growing around our grapevines, even around our hot tub. (We use no chemical fertilizers. Ours is just a suburban back yard lot with 30 Zinfandel vines grown as a hobby.) I’ve just been pulling it and tossing it, but went searching for *detailed* guidance on harvesting the seeds in cereal or baking (e.g., how do you separate the seeds from the chaff? is the flavor mild or strong?) to see if that would be practical. Not finding it here, which had been my hope.

I think the green parts of the plant are the chemical collectors not the seeds.

I live in Texas and am over run with this plant in my land. Regarding your comment that it isn’t reported in Michigan, I’m reporting it! I was at my dad’s house last week and pulled a 2 foot plant.

I just saw the Amaranth page https://www.eattheweeds.com/palmer-amaranth/

I am researching plants used worldwide, during famine https://www.purdue.edu/hla/sites/famine-foods and am writing to ask, if there are any references to A. Palmeri being used as such.

Thanks,

Bob Freedman

Tucson, AZ

I am not aware of any famine use but the female plant would be good for said as it makes a lot of edible pseudo-grain.

I just pulled quite a bit of this out of my garden. They were all young plants, less than 12″ tall. Are the roots edible also? They reminded me of bunching onions.

My back yard is full of common pigweed/amaranth –the kind that does not have male and female plants. I found just a few of this palmer type, and their leaves are more appealing to eat than the usual pigweed –finer, smoother, and darker green. They were actually nice looking plants. I don’t mind pigweed growing in the garden because we can just eat it, and it is pretty easy to pull out of the ground, especially while younger.