A true back yard salad, a hibiscus blossom is the center piece and decorations around the edge. The light blue flowers are tradescantias. (See Pocahontas entry) There are also bits of deep red H. acetosella leaves in the salad as well along with purslane (see omega 3 fatty weed entry.) The dressing is blackberry yogurt with balsamic vinegar and olive oil

Lunch Landscaping: Hibiscus

My mother’s favorite flower was the Rose of Sharon, which of course didn’t even go in one of my ears and out the other when I was a kid. But now that she’s passed (at 88) and I like plants I pay more attention. The Rose of Sharon is Hibiscus syriacus (high-BISS-kuss seer-ee-AY-kuss) meaning “slimy from Syria.” It’s a mallow family member and besides mom’s favorite it happens to be the national flower of South Korean, fitting since the flower is an Asian native. (They first thought it came from Syria, hence the name.)

In Korean, H. syriacus is called mugunghwa, which is a variation of the word mugung, meaning “immortality.” H. syriacus is also called the Rose of Althea, which is from Greek meaning “truth.” Actually, hibiscus is also a Greek word. More on that in a moment. H. Syriacus is a flower that has prompted folks to be poetical for a long time. And regardless of what it is called, the hibiscus is a mallow and people have been using plants in the mallow family for a very, very long time.

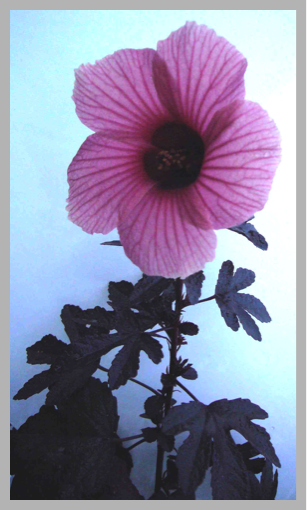

Mallows are quite consistent in their signature flower: Five separate petals with the male and female parts fused together like a frilly spike in the center, typified by the top left picture of a hibiscus taken in Greece at the cave of St. John, on Patmos. Some part of a Mallow is usually mucilaginous, meaning slimy. Crush almost any part of the plant and rub it between your fingers, they will be slimy or sticky.

The medicinal properties of the wet-footed low-growing marsh mallow were mentioned by Horace, Virgil, Dioscorides and Pliny (and from whence where the original marshmallow of peanut butter sandwich fame came from.) The Egyptians and the Chinese used the mallow. It was even mentioned in the Bible, book of Job, 30: 3-4: “For want and famine they were solitary; fleeing into the wilderness in former times desolate and waste. Who cut up mallows by the bushes, and juniper roots for their meat.”

Pythagoras, the Greek philosopher and mathematician, advised against eating the marsh mallow because it was, in Greek theology, the first messenger sent to earth by the gods to show their sympathy with the short lives of mortals. Thus eating mallow would dishonor the gods. The word mallow itself comes from the Anglo Saxon word Malwe. That came from the Greek malakos, for soft. Even Shakespeare mentions mallows, in The Tempest. Gonzalo is saying “Had I plantation of this Isle, my lord…” when he is interrupted by Antonio and Sebastian saying: “He would sow it with nettle-seed. Or docks or mallow.”

The most common form of mallow most folks see these days is the hibiscus, and that’s what is pictured on this page. It’s a very common landscape shrub in warm areas and at least one species— Malvaviscus arboreus (mal-vah-VIS-kus ar-BOR-ee-us) the tubular flower to the right —has escaped cultivation and naturalized. It is also called Malvaviscus penduliflorus.

I usually put hibiscus flowers in salads. They don’t have any flavor but they are pretty and add texture. The leaves of some hibiscus are edible as well, such as pink hibiscus with red leaves on this page, upper right. Called the False Roselle, its Latin name is Hibiscus acetosella (hye-BISS-kus uh-set-o-. SEL-luh.) As mentioned, hibiscus means hibiscus or slimy or sticky, and acetosella means “a little sour.” Besides the flowers of the H. acetosella, I use the young leaves for salads and stir fry. A close relative, H. sabdariffa (hye-BISS-kus sab-duh-RIF-fuh) is the real roselle and is also known as the “Florida Cranberry” the “Cranberry Hibiscus” and the Jamaican Sorrel, thought the latter strikes me as recent and nescient. A tart juice can be made from its fat calyxes and it’s something of a tradition in the West Indies. Many posters on the internet get these two hibiscus mixed up, but there is no need for it. The False Roselle ( H. acetosella) resembles a small red maple where as the Cranberry Hibiscus (H. Sabdariffa) has lance-shaped, green leaves. They look quite different in leaf shape and color.

Better known members of this family today are okra and cotton. Cotton is the only mallow with proven toxic properties. While refined cottonseed oil is common — the basis for Crisco shortening (the names comes form Crystalized Cotton Seed Oil) in its raw state it reduces potassium in the body and increases infertility. Oddly it is also often used to pack smoked oysters.

As for okra many folks don’t like its viscus texture but it brings up the origin of words. Viscus and hibiscus come from the same Greek word, “iviscos” which means hibiscus and has come to mean thick or sticky as in a viscous fluid. The base word in Greek is EE-vis, a marsh wading bird still found in English as Ibis.

While the nutritional value of the H. acetosella (the pink one with the red leaves) is not known, here is the nutritional breakdown of a close, edible relative:

Flowers (Fresh weight) Water: 89.8 Protein: 0.06 Fat: 0.4 Fiber: 1.56 Calcium: 4 Phosphorus: 27 Iron: 1.7 Thiamine: 0.03 Riboflavin: 0.05 Niacin: 0.6 Vitamin C: 4.2

Fruit (Dry weight) Calories: 353 Protein: 3.9 Fat: 3.9 Carbohydrate: 86.3 Fiber: 15.7 Ash: 5.9 Calcium: 39 Phosphorus: 265 Iron: 17 Thiamine: 0.29 Riboflavin: 0.49 Niacin: 5.9 Vitamin C: 39,

Leaves (Dry weight) Protein: 15.4 Fat: 3.5 Carbohydrate: 69.7 Fiber: 15.5 Ash: 11.4 Calcium: 1670 Phosphorus: 520

One mallow is a famine food, the Caesar Weed, see an article elsewhere here on the Caesar Weed, Urena lobata. Also edible is the leaves of the Abelmoschus manihot.Two final nibblettes: Some times marsh mallows are called cheeses That’s because the flat, round, seed pod of the marsh mallow looks something like cheese. And, the mineral malachite is named after the mallow because its green color is similar to the mallow green.

Green Deane’s “Itemized” Plant Profile

IDENTIFICATION: The leaves are alternate, simple, oval to lance shaped, often with a toothed or lobed. The flowers are large, obvious, trumpet-shaped, with five or more petals, ranging from white to pink, red, purple or yellow. The fruit is a dry five-lobed capsule, containing several seeds in each lobe.

TIME OF YEAR: Can bloom year round in warm areas.

ENVIRONMENT: H. acetosella prefers most well-drained soil. It cannot grow in the shade. It requires moist soil.

METHOD OF PREPARATION: Flowers and young leaves of the H. acetosella can be eaten raw, chopped leaves an be added to stir fries.