Hardy Orange, sometimes in the citrus clan, sometimes not. Photo by Aubree Cherie

Is the Hardy Orange edible? That depends on how hungry you are, or which century you live in.

A native of China, Hardy Orange (Poncirus trifoliata) aka Trifoliate Orange, was once grown in northern Europe where the fruit rind was candied and dried. As a cold-hardy pseudo- citrus American colonists also grew the Hardy Orange because the fuzzy fruit has pectin which was used in making jams and jellies. The fruit, minus, seeds, was also made into a not-sweet marmalade. In China the bitter fruits were used as seasoning (dried and powdered) and young leaves are occasionally boiled and eaten. Fresh fruit allowed to sit for two weeks after picking yields about 20% juice which can be diluted and made into a drink. The flavor is a cross between lemon and grapefruit. A slice of it is good in a gin-and-tonic. Do note that processing leaves a hard-to-wash off resin on utensils. The University of North Carolina, which I think believes every plant is toxic, lists the Hardy Orange as “poisonous.” It says the fruit can cause “severe stomach pain and nausea, prolonged contact can cause skin irritation.” But it also says “causes only low toxicity if eaten, skin irritation minor, or lasting only for a few minutes.” The fruit may also have some anti-allergic activity. In Chinese medicine it has been used to treat typhoid, toothache, hemorrhoids, conjunctivitis, colds and itchy skin.

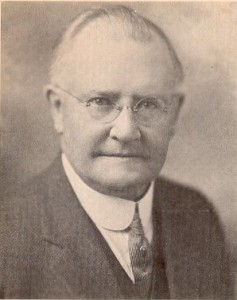

The Hardy Orange is naturalized in the United States from Pennsylvania south and west to northern Florida and eastern Texas. In recent times Poncirus trifoliata has been used primarily as root stock for citrus along with at least three developed cultivars: Barnes, Rubidioux, and Flying Dragon, the latter of which has curved thorns. Interestingly while the original species came with the colonists the Flying Dragon was introduced from Japan to the U.S. in 1915 by American botanist Walter Tennyson Swingle (1871-1952). Swingle’s first major job was not far from here in Eustis, Florida, in 1892. He and Dr. Herbert John Webber experimented with citrus and formed the basis of much of what is known about citrus. They created Tangelos including the Minneola and crossed the Poncirus trifoliata with Citrus sinensis to create the Citrange, common in many landscaped gardens. In 1943 Swingle wrote “The Botany of Citrus and Its Wild Relatives of the Orange Subfamily.” Webber, by the way, was no botanical slouch either. He wrote over 300 research papers and created many cotton species that are still used in the clothes you wear.

Like many thorn-ladened trees, birds select the Hardy Orange to make their nests in as the two-inch thorns dissuade predatory creatures. The tree can be used as a natural fence and have often been used to corral livestock. The thorns are sturdy enough to puncture a tire or use as a tooth pick. The wood is extremely is hard and dense, the bark striped with green, stems are triangular. Early spring flowers are popular with bees and butterflies. Deer don’t like it nor rabbits. The aromatic fruit, ripening in the fall, can also be dried and used in potpourri mix. Fall foilage is butter-yellow.

The Hardy Orange grows to about six feet (sometimes 20 feet!) and starts bearing around 12-years old. They are a common bonsai specimen. It loses its leaves in winter and can be grown in protected areas as far north as Canada. It has been cultivated in China for thousands of years and in Japan since the 8th century. As mentioned above it came to North America in colonial times and was introduced into Australia in the late 1800s. It is also commonly used in Argentina. Hardy Orange prefers low-lime soil.

The botanical name, Poncirus trifoliata, is said pon-SEER-us try-foh-lee-AY-tuh, some say pon-SIGH-russ. Poncirus is from French meaning a citron. Trifoliata means three leaves.

Green Deane Itemized Plant Profile: Hardy Orange

IDENTIFICATION: Poncirus trifoliata: Tree to 20 feet, leaves alternate, compound, three leaflets, 1 to 2 inches long, may be finely wavy toothed, thickened, petiole winged, shiny dark green, flowers white, cup-shaped, fragrant. Vicious thorns, small fruit. Self-fertile, propagate by planting fresh seeds from ripe fruit. If you are going to store the seeds keep them cool (35-40F for at least 30 days) then warm for 24 hours in warm water. Chilled seeds germinates in two weeks if kept around 70-80F, a month at 60-70F. Poncirus is a monotypic genus with the only member the trifoliata.

TIME OF YEAR: Flowers in early spring, fruit in late fall.

ENVIRONMENT: Not too picky about soil but does not like line-heavy soil, prefers full sun but can tolerate some shade. Likes moist soil but will not tolerated being water logged.

METHOD OF PREPARATION: Fruit as marmalade, dried as seasoning, juice diluted for a drink.

Hardy Orange Marmalade

Use 30 to 50 fruit depending upon their size. Wash well. Cut each one equatorially and twist the halves apart. Squeeze the pulp, seed and what juice there is into a bowl. Remove the seeds. This is helped by adding a little water. You can slice the peelings or leave them whole.

Add the peelings to a jar holding 2.5 cups of water and 1/8 teaspoon of baking soda. Bring to a boil and simmer for 10 minutes. Pour off about 2 cups of the water. Add the juice and pulp and simmer for 10 more minutes. Meanwhile put enough jars (lids and screw-caps) for eight cups of marmalade into a big pot of water and bring them to a boil. Continue to let them boil very gently until the marmalade is ready to can.

Measure 4 cups of sugar then take 1/4 cup of that sugar and mix it with one package of pectin in a small bowl. In the large bowl add enough water to the juice/pulp mixture to bring the volume to 5.5 cups and put it in a gallon pot for cooking. Add the sugar/pectin mixture from the small bowl and a 1/2 tablespoon of oil. Bring a full boil stirring constantly as it heats. Then add the rest of the sugar and heat this till it again reaches a full boil. Boil for one more minute only. Turn off the heat and quickly put the marmalade into the sterile jars. Fill each jar to within 1/4 inch of the top, wipe off any marmalade that touches the rim. Set the lid, tighten, then do the next jar. Sealed jars should keep for months.

If you want to reduce the bitterness of the peelings first you can parboil them in as many changes of water as you like until the water is not bitter or of a bitterness of your liking. Cooking will leave a resin on your utensils. Alcohol will remove it quickly.

Herb Blurb

Antianaphylactic activity of Poncirus trifoliata fruit extract.

Source

Department of Oriental Pharmacy, College of Pharmacy, Wonkwang University, Seoul, South Korea.

Abstract

The effect of an aqueous extract of Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf. (Rutaceae) fruits (PTFE) on compound 48/80-induced mortality associated with anaphylaxis was studied in rats. PTFE inhibited compound 48/80-induced anaphylaxis 100% with a dose of 1.6 mg/g body weight (BW) 1 h before or 5 min after injection of compound 48/80. PTFE inhibited compound 48/80-induced anaphylaxis almost 100% with doses above 0.4 mg/g BW intraperitoneally administered. PTFE (1-1000 micrograms/ml) also dose-dependently inhibited the histamine release induced by compound 48/80 (5 micrograms/ml) in rat peritoneal mast cells. The level of cAMP in peritoneal mast cells, when PTFE was added, increased transiently, and significantly increased 53-fold at 10 s compared with that of basal cells. Moreover, PTFE inhibited intracellular calcium release induced by compound 48/80. These results suggest that PTFE has antianaphylactic activity by stabilizing the peritoneal mast cell membrane.

Anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of the metabolites of poncirin from Poncirus trifoliata by human intestinal bacteria.

Source

College of Pharmacy, Kyung-Hee University, Seoul, Korea.

Abstract

Poncirin was isolated from water extract of the fruits of Poncirus trifoliata and metabolized by human intestinal bacteria. The inhibitory effect of poncirin and its metabolites by these bacteria on the growth of Helicobacter pylori (HP) was investigated. Among them, ponciretin (5,7-dihydroxy-4′-methoxyflavanone), the main metabolite most potently inhibited the growth of HP, with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 10-20 microg/ml. However, poncirin and its metabolites except ponciretin did not inhibit the growth of HP, nor did they inhibit HP urease.

Anti-inflammatory effect of Poncirus trifoliata fruit through inhibition of NF-?B activation in mast cells

Abstract

Mast cell-mediated allergic inflammation is involved in many diseases such as asthma, sinusitis, and rheumatoid arthritis. Mast cells induce synthesis and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-? and interleukin (IL)-6 with immune regulatory properties. We investigated the effect of the fruits of Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf (Rutaceae) (FPT) on expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines by activated human mast cell line, HMC-1. FPT dose dependently decreased the gene expression and production of TNF-? and IL-6 on phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and calcium ionophore A23187-stimulated HMC-1 cells. In addition, FPT attenuated PMA and A23187-induced activation of NF-?B indicated by inhibition of degradation of I?B?, nuclear translocation of NF-?B, NF-?B/DNA binding, and NF-?B-dependent gene reporter assay. Our in vitro studies provide evidence that FPT might contribute to the treatment of mast cell-derived allergic inflammatory diseases.

Poncirus trifoliata fruit induces apoptosis in human promyelocytic leukemia cells

Volume 340, Issues 1–2, February 2004, Pages 179–185

Abstract

Background: Substances inducing apoptosis have shown efficacy in the treatment of cancers. Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf. (Rutaceae) fruits (PTF) has been used for the treatment of various cancers among Korean Oriental Medical doctors. Methods: PTF-induced cytotoxicity of human leukemia HL-60 cells was monitored by the MTT assay. The apoptosis was determined by (a) apoptotic morphology in microscopy; (b) DNA fragmentation in electrophoresis and FACS analysis; and (c) activation of caspase-3 and poly-ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) cleavage assay. Results: The cytotoxic activity of PTF in HL-60 cells was increased in a concentration- and time-dependent manner. PTF caused the cell shrinkage, cell membrane blebbing, apoptotic body and DNA fragmentation. PTF-induced apoptosis is accompanied by the activation of caspase-3 and the specific proteolytic cleavage of PARP. However, PTF did not show cytotoxicity in normal peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Conclusions: Our novel finding provides evidence that PTF could be a candidate as an anti-leukemic agent through apoptosis of cancer cells.